Sometimes, corporate chieftains actually step forward to apologize for the abuse they inflict on workers, consumers, communities, and the environment.

The word “sometimes” makes such apologies seem more common than they are. “Once in a blue moon” is more like it. Also, “apologize” suggests contrition and a willingness to accept responsibility, neither of which they mean when they use the word. In corporate-speak, apologize is a slick synonym for dodge, duck, and divert.

A fine demonstration of the art of corporate apology recently came to us from South Korea. While that country is an ocean away from America, the company involved is quite close to us: Samsung, the world’s largest maker of smartphones and memory chips, is a leading purveyor of tech gizmos and their components.

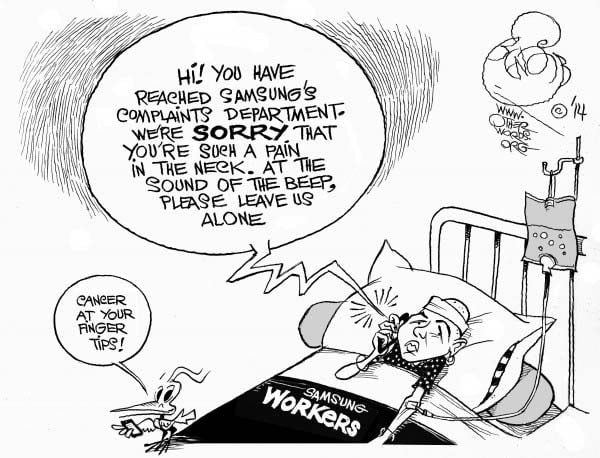

Samsung’s Complaints Department, an OtherWords cartoon by Khalil Bendib

Samsung’s Complaints Department, an OtherWords cartoon by Khalil Bendib

Most smartphone buyers may not realize this, but those devices are being made with a cancer-causing mix of toxic chemicals. Samsung’s Korean chip-factory workers have suffered leukemia and other cancers linked to those poisons.

For years, a South Korean grassroots movement has pressed the corporation and government for compensation to victims — and an apology. In May, activists finally scored a victory…sort of.

Under pressure from the public, legislators, and the courts, a top Samsung executive promised payments to victims and offered “our sincerest apology to the affected people.”

However, the apology was no mea culpa, no expression of penitence. Indeed, Samsung made clear that it does not admit that there’s any link between the chemicals it uses and the illnesses and deaths of workers. Rather, the corporation is simply expressing vague sorrow that workers get cancer for whatever reason.

Basically, the message is: “Sorry you’re dead. Not our fault. Here’s some money. Now, go away.” But that doesn’t make the cancer problem go away.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $33,000 in the next 2 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.