Observers and pundits are predicting record-setting voter turnout in the coming election. But the number of votes from Indian Country may be underwhelming because of systemic problems.

University of Florida Political Science Professor and U.S. Elections Project Director Michael McDonald said turnout on Nov. 3 may well be the highest since 1908, when 65.7 percent of voters cast ballots. That percentage this year would bring in 145 million votes.

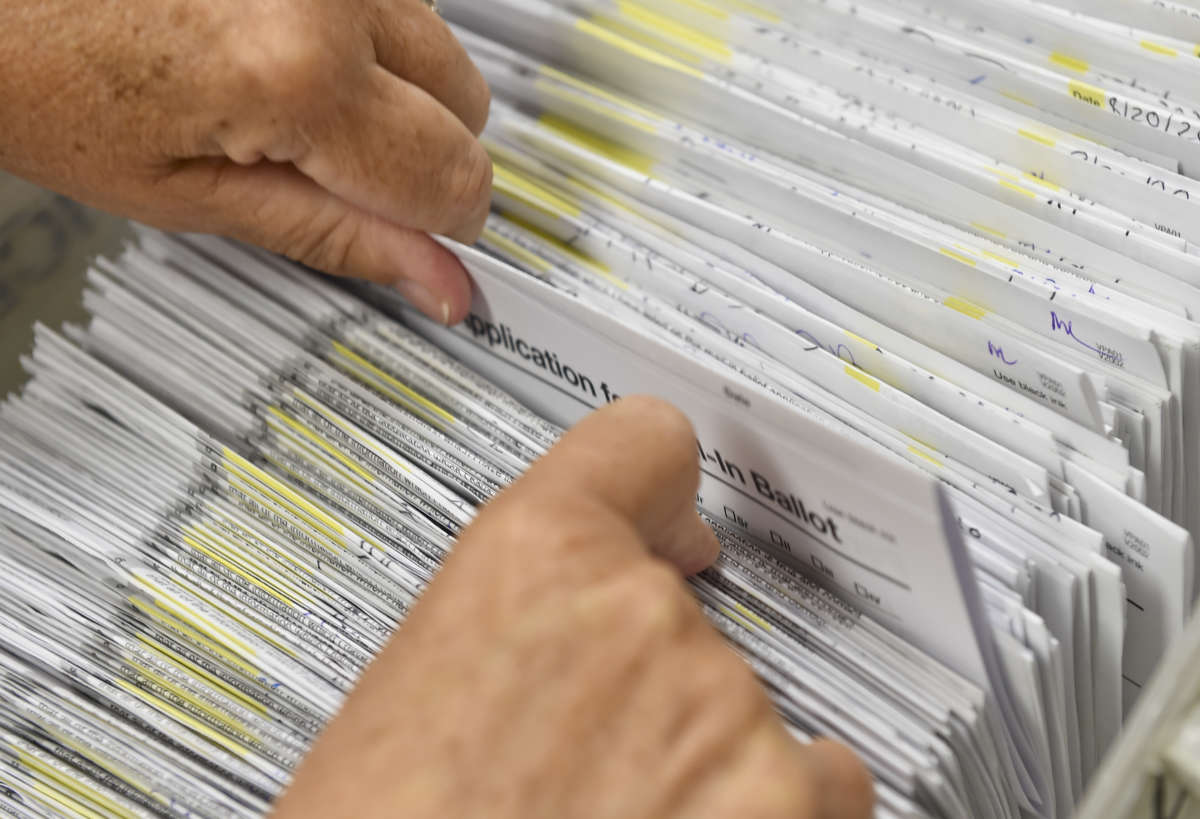

To reduce the spread of COVID-19, experts recommend people vote by mail. In several states, and for certain populations, vote by mail is standard practice. Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, Utah and Colorado residents vote primarily by mail. Federal law protects military voters’ rights to vote by mail and electronically. And for more than a century, every state has allowed absentee ballots to be returned by mail.

“I’m expecting that half the votes, at least, will be cast by mail, in the upcoming November election,” McDonald said. He’s expecting more than 70 million people to cast a mail ballot.

As it stands now, some of those voters will be disenfranchised.

For one thing, laws in most states are at odds with what the post office can handle, a gap high volume will only make worse.

U.S. Postal Service Chief Counsel and Vice President Thomas Marshall recently warned election officials in 46 states that their deadlines are “incongruous” with postal delivery standards. Marshall said in some states, laws allow people to request ballots so close to Election Day, there’s no way the ballot can be received and returned by mail in time.

Vote by Mail Problems in Indian Country

“We’re all for increased vote by mail,” Jacqueline De León, Isleta Pueblo, told the Navajo-Hopi Observer. She’s an attorney with the legal assistance nonprofit Native American Rights Fund and co-author of the report “Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters.”

But, De León said, “we’re absolutely against all vote by mail.”

“If there are no in-person opportunities, then Native Americans will be disenfranchised because it will be impossible for some of them to cast a ballot,” she said.

The nonprofit’s report shows as few as 18 percent of Native Americans receive mail at home, primarily because they lack traditional residential addresses.

De León said voter suppression is also an issue. She pointed to North Dakota, which in 2012 passed voter ID requirements that critics said placed undue hardships on people living on reservations.

The Native American Rights Fund and other groups sued and managed to get that law tempered. The settlement ensures Native voters can present tribal IDs or even simply point out on a map where they live.

In Alaska, discrimination in voting rights has been the subject of lawsuits as recently as 2007 and 2013. In one of the suits, evidence included a 100-page English language election booklet shown next to the one-page Yup’ik language sheet that included only the date, time and location of the election.

De León was concerned that North Dakota was switching to an all vote-by-mail election, “which could once again silence Indigenous people, many of whom only get mail at far-flung post offices that aren’t consistently open.” North Dakota officials have said they were working closely with tribal leaders to install more ballot drop-boxes on reservations.

McDonald said officials need to know where voters live to place them in precincts, although some states have figured out workarounds.

“If people are concerned about this, and there are good reasons to be concerned about it … I would contact your local election official and find out, get some recommendations from them as to how to best get your ballot to you,” McDonald said.

Other problems, the fund’s report states, are:

- A lack of tribal community polling stations where people can drop off ballots in person

- A lack of internet service to access voter information or to request an absentee ballot

- Long distances to reach post offices open for only limited hours

Those hurdles may explain why in the 2012 election in Montana, only 10 to 15 percent of ballots from reservation communities came by mail, compared with 33 percent from the rest of the state.

Another concern is that states vary widely in their experience and readiness to hold an election by mail. For example, in 2016, just 2 percent of voters in West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee voted by mail.

Also, FiveThirtyEight and The New York Times have found gaps in ease or difficulty among states that allow voting by mail.

- In nine states and Washington, D.C., ballots are automatically sent to every voter

- In nine states, applications for mail-in ballots are automatically sent to every voter

- In 25 states, voters must request or pick up an absentee ballot to vote by mail

- In seven states, people can vote by mail only with a valid excuse (fear of contracting coronavirus doesn’t count)

- Some states will accept only absentee ballots delivered by mail

- Three states require notarization of ballots

- Six require witness signatures

In states that require witness signatures, those will be harder to get since the U.S. Postal Service recently prohibited workers from signing ballots as witnesses.

(To find out how your state rates on ease of voting by mail, click here).

If the Primaries Were a Test, Some States Flunked

Wisconsin was the first state to hold an election during the pandemic.

“There were lost ballots that were undelivered,” said McDonald. “There were ballots that voters would put into the mail, and then it would turn back up in their own mailbox. So there were these sporadic problems.”

Rural counties had problems with ballots coming in too late to be counted, he said.

Results of New York City’s June primary showed 21 percent of mail-in ballots were rejected — some because the post office couldn’t handle pre-paid postage, others because they were sent out so late there was no way the voter could get them in time. The New York elections board also was short on staff due to COVID-19.

In Florida’s March primary, 18,000 ballots were rejected; Black and Hispanic voters were more likely to be voting by mail for the first time and, if so, were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected than White voters who were voting by mail for the first time, NPR reported.

Basically, McDonald said it will boil down to whether the ballot is “signed, sealed and delivered.” He said it’s “really important that people follow the instructions very carefully because most frequently people disenfranchised themselves.”

The most common reasons for ballot rejection are because of a missing signature, an unverified signature or late arrival. But some were rejected because the envelope was taped shut instead of sealed; others because the wrong envelope was used.

McDonald recommends people request their ballot as soon as possible. He said North Carolina, for instance, is sending out ballots beginning this week.

Arizona State University policy assistant Coby Klar suggested other ways Arizona, among other states, could make it easier for Native Americans to vote by mail: Use tribally designated buildings as drop-off sites, set up curbside drop-off, and provide on-site language assistance, paid postage and education campaigns.

Still, once the ballots are in the hands of election officials, the nonprofit public policy organization Brookings said, the flood of ballots will make it difficult for some states to get them counted in a timely manner.

Vote by Mail Still a Good Option

McDonald said a person may come away from all this with the idea voting by mail won’t work.

But, he said, despite President Donald Trump waving red flags about the potential for fraud with mail ballots, it’s a secure system. In states with all mail-in ballots, there are “lots of protections.”

“They are sending out ballots to voters. They’re barcoding everything. They’re doing signature verification checks,” McDonald said. “They can look at a long history of signatures of people that have returned their ballots because they’re digitizing them all.”

In states with experience in voting by mail, officials say rejection rates are below 1 percent.

With majorities in Congress and state legislatures and the office of the president at stake, tribal citizens’ votes can be decisive in close elections — if they vote, and if their votes are counted.

At least two sitting U.S. senators — Republican Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Democrat John Tester of Montana — credit their latest wins to the Native American vote.

CNBC reports the Native vote could influence this year’s election results in seven major swing states: Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, North Carolina, Wisconsin and Colorado, according to data from Four Directions.

48 Hours Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $31,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 48 hours left to raise $31,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!