Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

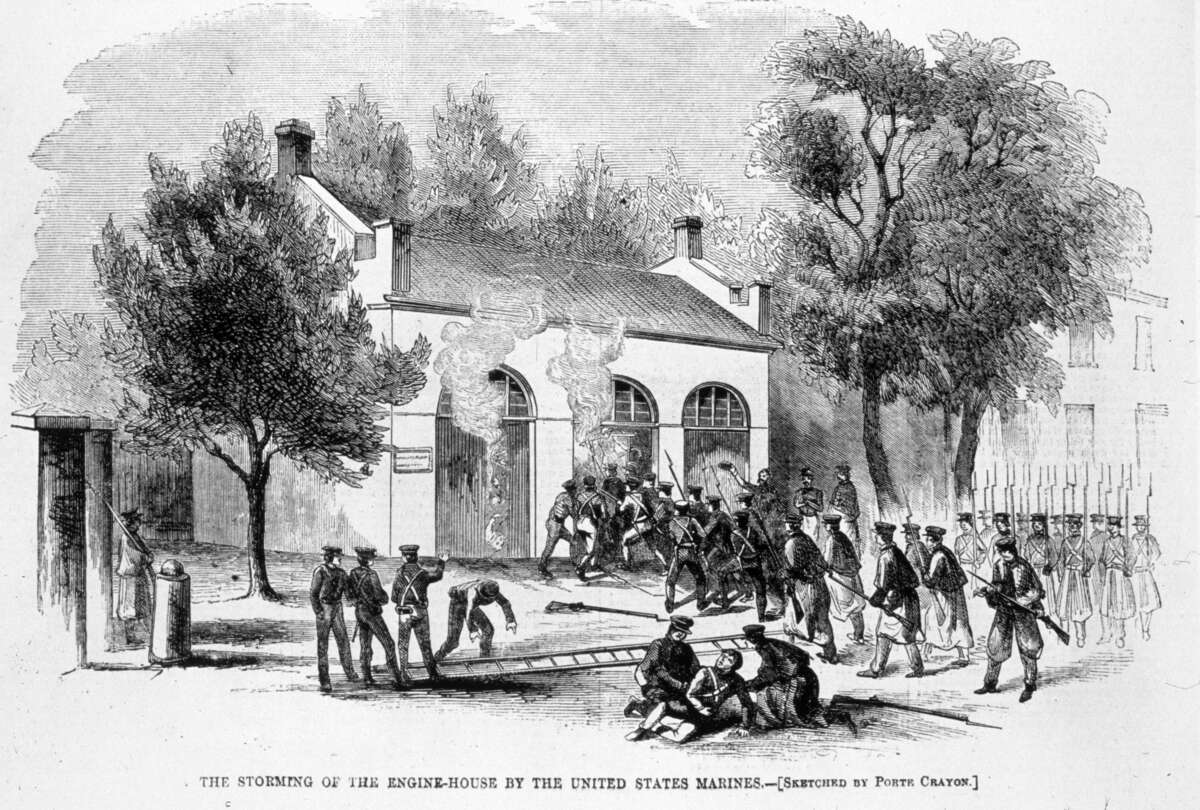

This week marks the 165th anniversary of John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry (in what is now West Virginia) in October 1859. The deeply religious Brown was an ardent white abolitionist determined to bring an end to slavery. He thought his raid on Harpers Ferry — waged by a small, interracial army of nearly two dozen men — would inspire an uprising of enslaved people across the South. The raid was quickly crushed by federal and local troops, and most of John Brown’s army perished in the fighting or were executed soon after.

In the following weeks, though, the bold action polarized the U.S. and galvanized the abolitionist movement. Sentenced to death, John Brown calmly explained to the nation why he was willing to die in the fight to end slavery. “If it is deemed necessary,” he famously said in court, “that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments — I submit; so let it be done!”

Executed on December 2, 1859, Brown became a martyr of the abolitionist cause and the struggle for racial equality, and generations since have revered him as an inspiration. His complete abolitionist commitment and his raid on Harpers Ferry continue to raise important questions about the relationship between bold initiative and wider change, the role of armed violence in movements and the true meaning of solidarity.

In this exclusive Truthout interview, historian Manisha Sinha discusses the historical context for John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, how Brown drew inspiration from the Black abolitionist tradition, lessons from the abolitionist movement, John Brown’s historical legacy, and more.

Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She is the author of several books, including the magisterial, award-winning The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, of which a New York Times reviewer noted: “It is difficult to imagine a more comprehensive history of the abolitionist movement.” This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Derek Seidman: Can you discuss the historical context in the U.S. and among abolitionists in the 1850s for John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry?

Manisha Sinha: The 1850s are a crisis decade in U.S. history in terms of the sectional conflict between the North and South. It’s just before the Civil War. The Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850, and that angered many northerners because it basically tried to make them into slave patrollers and get rid of the protections that abolitionists and anti-slavery politicians had put into place for fugitive slaves.

John Brown and other abolitionists are radicalized by this. In 1851, Brown forms the League of Gileadites, an all-Black militia in Springfield, Massachusetts, to oppose the implementation of the Fugitive Slave Act. He has plans to storm northern courtrooms and forcibly prevent the rendition of runaway slaves — who we today call Freedom Seekers.

This is very much in the mode of the abolition movement and what Black people had been doing for a long time, which is violence in self-defense. Throughout the 1850s, this stance of evoking direct action, because all appeals to the law had failed, radicalized the movement and people started visualizing direct confrontation with southern slaveholders. Brown is very much coming out of this milieu.

In the 1850s you also had the fight over Kansas, over whether it should be a free or slave state. Kansas was in a state of upheaval with a sort of dress rehearsal to the Civil War itself, largely perpetrated by slaveholders and their allies.

This is when John Brown said, we can’t just let them get away with this. He moved to Kansas with some of his sons and fought them to the nail. John Brown and his sons killed some pro-slavery settlers in the so-called Pottawatomie Massacre, which is quite famous. These settlers were not some innocent guys. They had been involved in enslaving and abusing Indigenous people, and they had threatened the Brown family before.

What, then, sets the stage for the raid on Harpers Ferry?

Throughout the 1850s, southern slaveholders and their northern Democratic allies completely controlled the federal government. You had an awful Supreme Court under Roger B. Taney that issued the Dred Scott decision. Meanwhile, the Slave Power [what abolitionists called the entrenched power of slaveholders in the U.S.] is getting more aggressive in Kansas. They want to reopen the African slave trade. They are forcing the federal government to pass draconian laws to enforce slavery. It looks like abolitionists have exhausted other means.

That’s where Harpers Ferry comes from. By the time of Harpers Ferry, John Brown has decided that he’s going to wage a war against slavery. He meets with Black abolitionists and white supporters. He lays out his plan, which, in the beginning, is simply to form what he called a “subterranean passageway” to the North, through the Appalachian Mountains, and even form a kind of a self-governing community of formerly enslaved people that would enfranchise Black people. He also had women’s suffrage in his provisional constitution.

John Brown wants to recruit a neighboring enslaved population to strike a blow against slavery. He is completely confident that enslaved people will rise up and that this would end slavery. He believed this was the only way, because, in the 1850s, it didn’t seem likely that slavery would end. I’ve argued we should call John Brown a revolutionary abolitionist. He wanted to start a revolution against slavery. Those historians who call John Brown a “terrorist” are using anachronistic terms to describe the abolition movement and its radicalization, and John Brown himself.

How was John Brown influenced by the Black abolitionist tradition?

It’s really important to see John Brown within a tradition of Black radicalism, including the Haitian Revolution, a slave rebellion that leads to the world’s first Black republic. Brown and most abolitionists, even pacifists like William Lloyd Garrison, completely admired the Haitian Revolution and Toussaint L’Ouverture. Garrison held Toussaint L’Ouverture in higher esteem than George Washington because he freed his country but also ended slavery.

When Nat Turner’s rebellion takes place, some of the only people to defend him are abolitionists. Even pacifists like Garrison defended Turner’s rebellion, in which he killed all slaveholders and enslaving families he came across. Very few people defended it. Abolitionists were the only ones.

Brown is coming from that tradition. He is enmeshed in the rhetoric and ideas of Black abolitionism. He admires the Jamaican Maroons. After Harpers Ferry, Black abolitionists put John Brown in the same tradition as Nat Turner. The Anglo-African magazine says now we will have either Nat Turner or John Brown’s way of getting rid of slavery.

I think Brown is a great example of interracialism in the abolitionist movement that is often forgotten. Brown’s father was one of the founders of the Western Reserve Anti-Slavery Society in Ohio. Brown admires the Black radical tradition, clearly, and he’s also very conscious of and influenced by the transnational fight against slavery.

What was the immediate impact of the raid on Harpers Ferry within the U.S.?

Harpers Ferry is seen as one of those stepping stones toward the Civil War. In a way, Brown steals victory from defeat. It’s not the raid on Harpers Ferry that becomes consequential; that quickly failed. It’s Brown’s incarceration and his last words to the nation from the courtroom. They’re really evocative, and he gets his message across. He says that he was hoping to get rid of slavery by shedding a little bit of blood, but now fears there’ll be a real bloodletting. He’s kind of predicting the Civil War. He says he only did what anyone would do in the fight for liberty, and he evokes American revolutionary traditions.

His words have an impact in the North, beyond even abolitionist circles. The Republican Party, including Lincoln, is trying to win the elections in 1860. They try to distance themselves from Brown because they are nervous they’ll lose support among northern moderates and conservatives. Lincoln, in his Cooper Union speech, makes it quite clear that he’s not a John Brown man. White southerners view John Brown as this awful, murderous person, and they try to associate the Republican Party with the radical abolitionists who, they say, just want to cut their throats.

Meanwhile, the abolitionists are all praising John Brown as a martyr to American freedom, and they really have an impact on northern public opinion. There’s an outpouring of sympathy for John Brown and his family in the North, especially among abolitionists, but also many others. When Brown is executed in December, church bells tolled across the North. That is a huge sea change in opinion in the North.

But it would be a mistake to say that Harpers Ferry was the direct catalyst for the Civil War. The South secedes in the winter of 1860 and 1861 when Lincoln wins the presidential election. It secedes when it loses state power. They refuse to accept the results of the election. So ironically, it was not the radical abolitionist John Brown, but the election of an anti-slavery moderate politician like Lincoln to the presidency, that convinces the South to secede.

What should activists today learn from John Brown and the abolitionists?

Radical social movements have been the way that political change has happened in U.S. history and the way the boundaries of American democracy have been expanded.

You can’t even imagine the rise of a free soil Republican Party — which in the 19th century was the party of anti-slavery liberalism and big government, just the opposite of what it stands for today — or the election of Abraham Lincoln without the abolitionist movement preparing that ground for 30 years. No one else wanted to talk about slavery. Nor can you imagine Reconstruction and its agenda of Black citizenship and equality without the abolitionists.

What the abolitionists accomplished was simply remarkable. They accomplished the rise of a third party. The Republican Party basically replaced the Whig Party, which disintegrated over the question of slavery. Since then, we have not had a successful third party in the United States.

Abolitionists themselves differed on the best method for change. Garrison found the entire state and church in the United States complicit with upholding slavery. He felt that the moment you entered politics, you entered the realm of compromise. But you also had people like Frederick Douglass who, later on, thought maybe they could affect change within the system. In the end, both were right. By the Civil War, Garrison, who was committed to this radical social movement, also became a defender of Lincoln and the Republican Party, because, he said, that’s what you can get in the current political system.

These are exactly the kind of debates that activists have today. Can you use the system to affect change, or do you need to completely reject it and form an alternative path? Many historians think these internecine divisions made abolitionists ineffectual, but I think it helped them, because they had a variety of viewpoints on how to affect political change.

The question of principle versus pragmatism seems like an endless debate on the left.

You have to retain the kind of purity that Garrison had when it comes to activism, but also the kind of pragmatism that he had when you view the lay of the land. You should figure out which government or party you can influence, and where you might have absolutely no say. That’s an important lesson from the abolitionists, who were radical in their principles, but when it came to politics, got pretty pragmatic quite fast. That’s why they were able to win in the end.

Before his death, Lincoln becomes the first American president to endorse Black male suffrage, setting the stage for Reconstruction. This is the same guy who, in the 1850s, is thinking about colonization and sending free Black people to Africa. But by the end of the Civil War, he’s thinking of Black citizenship. That’s a huge evolution, but it’s not about Lincoln. Abolitionists just don’t get enough credit. This was their agenda. Within the administration and outside it, they were able to agitate for their principles.

The raid on Harpers Ferry failed. But in the larger arc of history, what is the verdict on John Brown?

I think John Brown lives, and I think he’s victorious in history. There were radicals and revolutionaries all around the world, immediately after Harpers Ferry, who were praising him. There was even someone from the Paris Commune, Pierre Vésinier, who was a big admirer of John Brown. Revolutionaries all over the world recognized John Brown as a kindred spirit.

Black intellectuals and activists outside mainstream academia, like W.E.B. Du Bois, started writing the first biographies of abolitionists like John Brown. But for decades, the mainstream academics who were John Brown’s biographers bought into scientific racism and wrote what Du Bois called the “The Propaganda of History.” These were highly biased accounts of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

It was just complete nonsense and not based on real research. These were the people, especially southern historians who had an ax to grind, who were shaping views of John Brown. They were propounding their “Lost Cause” ideas that became entrenched in American history and culture. This is when Confederate statues went up. It’s not until the George Floyd protests that these damn statues increasingly start to come down.

If you look at John Brown biographies today, or how he’s depicted in mainstream historiography or popular culture, I think his legacy and reputation are secure. There’s this wonderful television series, The Good Lord Bird, based on James McBride’s novel on John Brown, for example. Today we read works like Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction. Who reads the Dunning School anymore? So clearly, John Brown has won in death, and his legacy lives on.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.