Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Indigenous peoples’ territories are some of the few places where natural resources are preserved throughout the world. In fact, they protect about 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity but are legal owners of less than 11 percent of these lands, according to the World Bank. Because of this — and the fact that so many companies hope to get a piece of these resources — Indigenous peoples are often in a vulnerable position, and in a permanent kind of war with businesses and governments.

The International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ Rights, together with the United Nations 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, have been the main international legal tools to defend territorial rights. In theory, Convention 169 guarantees Indigenous people residing in the signatory countries the right to their land. To this end, it establishes that for any project that a company or government plans in their territories, they must be guaranteed a free, prior and informed consultation.

Because Convention 169 commits the signatory states to guarantee the integrity of Indigenous peoples, it’s been frequently invoked by Indigenous communities and peoples, especially in Latin America, when defending their territories in court. But the Convention has clear limitations that actually jeopardize its intent.

Indeed, the Convention is unprecedented in that it establishes that “all peoples have the right to self-determination.” But in several official yet not-so-public statements, the ILO makes clear how far it sees Indigenous rights as going: “One of the concerns expressed in both political and business circles has to do with a misinterpretation of the Convention where the outcome of the consultations could be the vetoing of projects. Said consultations don’t imply the right of veto and it’s imperative that an agreement or consent be obtained,” as stated in the document entitled “ILO Convention 169: Indigenous Peoples and Social Inclusion.”

While in many parts of Latin America, Indigenous peoples are defending their struggle for self-determination through consultations, for high-level ILO officials, the mechanism’s use is clear. “It’s not a ‘plebiscite’ to obtain a ‘yes or no’ vote, nor to obtain a ‘veto’ around decisions with general benefit. It’s a dialogue in good faith to enhance the benefits for Indigenous people regardless of the decision (the state) makes,” said Carmen Moreno, director of ILO’s Latin America regional office during the forum “Situation of the Right to Consultation in Convention 169,” which was held in conjunction with the World Bank in Guatemala in April.

In fact, according to the international organization, it’s governments that have the last word on Indigenous territories. “The power of the Convention is that it’s an instrument through which the peoples concerned can participate freely in a dialogue with the State. But the State, ultimately, is the one who must make a decision,” the ILO Convention 169: Indigenous Peoples and Social Inclusion reads. Regarding the most serious cases where peoples must be relocated from their territories, “even in these situations the people have no decision-making power,” said Moreno.

In addition, Convention 169 establishes that the rights of Indigenous peoples in relation to natural resources must be protected, but it does not grant them exclusive rights over those resources.

Garifuna community in Honduras, threatened by tourism projects and oil palm monoculture. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

Garifuna community in Honduras, threatened by tourism projects and oil palm monoculture. (Photo: Aldo Santiago)

Gold mine in a Honduran community. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Gold mine in a Honduran community. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Latin America: Principal Signatory

The Convention was signed in 1989 and went into effect in 1991. To date, 15 of the 22 countries that have ratified it are in Latin America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru and Venezuela. (In addition to Denmark, Spain, Fiji, Nepal, Norway, the Netherlands and the Central African Republic.)

The significant number of Latin American adherents to the Convention is not a coincidence. It’s an attempt to appease the high-intensity conflicts generated by the massive growth of development projects throughout the region. The Latin American Mining Conflict Observatory (OCMAL) points out that over the last decade, Latin America has become one of the epicenters of mining expansion.

“Guaranteeing indigenous people’s rights in Latin America: Progress in the past decade and remaining challenges,” a report put out by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), registered more than 200 conflicts in Latin American Indigenous territories linked to extraction of hydrocarbons and mining from 2010 and 2013.

Broran Indigenous territory, Costa Rica. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Broran Indigenous territory, Costa Rica. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Costa Rican government meeting in Broran territory, where drafting of the consultation protocol began. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Costa Rican government meeting in Broran territory, where drafting of the consultation protocol began. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Térraba: Marked Cards

Carmen Moreno claims that development is the main objective. “The consultations established in Convention 169 are an instrument of good governance to contribute to the development and growth of countries,” she said.

However, not everyone the Convention supposedly protects feels included. “They just forgot to ask if our definition of development is the same as their plan for our territories,” says Broran tribe member Pablo Sivar, from the Térraba-Boruca Indigenous territory in Costa Rica, who is a part of the Council of Elders. “I definitely don’t believe in their type of development.”

Sivar and his community are aware of impending threats to their lands and water. “In Térraba, there used to be a lot of water, but not anymore. And they wanna finish off the main river we have, the Térraba River, also known as river Diquís, which in the Boruca language means ‘big water’.”

He went on to explain that the El Diquís Hydroelectric Project would be the largest hydroelectric plant in Central America, despite official statistics that show that about 99 percent of the country already has electricity. “Who will the Diquís Project favor? Who it will develop? Is it the Térraba Indigenous people? Is it the Indigenous people of the south? Or is it just a few people?”

Work on the Diquís Project began in 2006. After much resistance by the local community, the project was halted in 2011. Without any additional information, the company simply announced — on the same day the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples James Anaya visited — that it would withdraw its machinery and infrastructure from Térraba territory.

Approximately three years later, the government arrived to begin developing a consultation protocol for Indigenous peoples, with the financial cooperation of international organizations, such as the ILO and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). This was announced at one of the government meetings in Térraba, where Truthout was. “We know why they’re here. We know what they want,” Pablo Sivar stated.

In the same meeting, the locals wanted to know if the process was linked to the Diquís Project. Immediately, government officials denied any link and tried to change the subject. “This process has nothing to do with the project. We’re here to develop a consultation protocol for Indigenous peoples,” said Ana Gabriel, Costa Rica’s vice minister for political affairs and citizen dialogue.

Government officials aren’t transparent about the link between projects and the protocol in these public forums, and make contradictory statements to the media. The plan to build the dam in Broran territory continues. The Indigenous consultation would be the last stage before handing in all necessary documentation to obtain environmental viability and move forward with the project. Feasibility studies and designs are already in place. The construction is scheduled to start in 2018, and operation in 2025.

The attempt to obscure the relationship between the protocol and the project is not in vain. The Indigenous resistance of the hydroelectric dam is longstanding. “We know that everything is ready for them to resume the work,” Cindy Broran of the Broran Indigenous Movement, founded by Térraba tribe members to resist the hydroelectric Project, told Truthout. “Consultation is the way to legitimize the company’s presence in the territory and with it they’ll be able to secure financing from international bodies, such as the World Bank. We know that everything’s in place.”

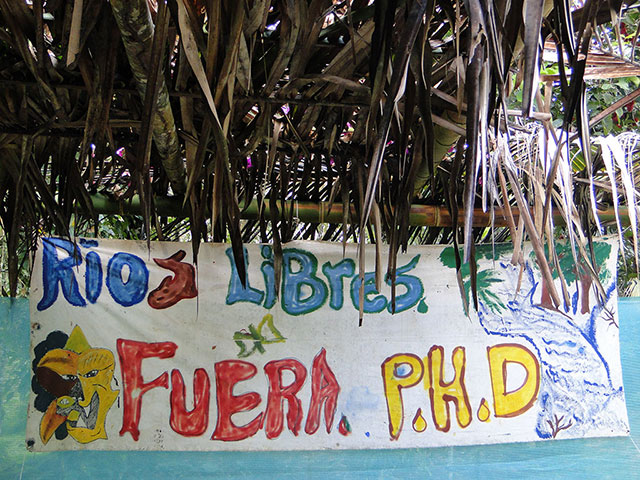

Broran territory. A dam-free zone. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Broran territory. A dam-free zone. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

The Térraba River in Costa Rica, where construction of the Diquis Dam is planned. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

The Térraba River in Costa Rica, where construction of the Diquis Dam is planned. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Project Halted Due to Lack of Consultation

According to Ana Gabriel, who’s responsible for developing the consultation protocol in Costa Rica, the country owes a historic debt to its Indigenous peoples and the current government plans on making up for it. “It’s no small matter that the president himself has issued a directive and given a mandate to develop this consultation protocol,” she told Truthout.

Despite the politically correct rhetoric of healing and historical debts to Indigenous peoples, the truth is that development projects, funded by international institutions, are unviable because of the lack of consultation. The vice minister of Costa Rica himself admitted it: “There have been projects that have had to be stopped in Indigenous territories due to lack of consultation.”

Baudillo Salles Sánchez, member of the Briri tribe, and his family. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Baudillo Salles Sánchez, member of the Briri tribe, and his family. (Photo: Renata Bessi)

Diquís Project: A Bitter Experience

In 2006, the Diquís Project began in Broran territory with a permit issued by the Development Association, a government entity responsible for land management. “Before we knew it, trucks, cars and people were entering the community,” said Broran. “We went to request information and they told us that they had moved forward with it because they had 76 signatures of people affiliated with the Development Association. The association gave the go-ahead for the company to come in and build the dam.”

“When the company moved in, it became chaotic,” Broran said. “They messed up the whole river, killing many species. Many shops sprang up to sell food, but mostly canteens and bars for workers from outside. The association gave permission for these businesses, without considering that Indigenous law prohibits the sale of alcohol within its territory. The illegal sale of land increased. Health centers and schools ran out of supplies.”

Additionally, ancestral patrimony of the Broran people was looted. Between 2006 and 2010, archaeologists contracted by the company did intense work, recounts Broran. They dug three tunnels that still exist. “We learned from folks who worked there that they found many archeological sites, including our ancestors’ cemeteries. They took everything they found. They took everything and we don’t know where it is.”

Oil palm monoculture which threatens Garifuna territory in Honduras.

Oil palm monoculture which threatens Garifuna territory in Honduras.

With Sights on Energy

Since the 1970s, the Costa Rican government has conducted studies to implement a hydroelectric project in the region. “Before, it was called Boruca Hydroelectric Project, which was about 15 km downstream from where the Diquís Project is today, but because of the resistance by the Boruca people, the project was cancelled. So, they moved it higher, in our lands, but it’s the same project. It will affect the same river only now on Broran ancestral lands,” Cindy Broran said.

According to a study by the World Rainforest Movement, geologists from the company Alcoa (where former US Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill was the CEO between 1987 and 1999) found deposits of bauxite in the General River Valley’s subsoil. Bauxite is the prime material used to make aluminum. In 1970, Costa Rica’s Legislative Assembly passed a law (No. 4562) saying Alcoa — one of the three largest aluminum companies in the world and considered a defense company since one of its main clients is the United States armed forces — could exploit up to 120 million tons of bauxite over 25 years and with a possible 15 years of extension, in exchange for building an aluminum refining plant in the same area.

Aluminum foundries require a great quantity of low-cost electric energy. The project is feasible provided a hydroelectric dam were to be built on the Rio Grande de Térraba, the study said.

The dam project triggered major resistance because many people considered it a violation and dangerous. Large demonstrations and protests took place, forcing Alcoa to give up its project.

The building of the Diquis Dam. (Photo: Community Archive)

The building of the Diquis Dam. (Photo: Community Archive)

Energy for the US

The Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) in charge of the Diquís Project has shifted its objectives. According to the document “National and Transnational Pressures on Energy in Costa Rica,” produced by the Association of Popular Initiatives Ditsö, the main reason for resuming construction of the hydroelectric project is the possibility of selling energy abroad, mainly to Mexico and the United States.

The dam is part of the Mesoamerica Project, initially called Puebla-Panama Plan (PPP) and funded by the United States government. It’s an initiative which, among other things, includes an extensive network of infrastructure projects from Mexico to Panama “necessary to export — or better yet, to plunder — many of our natural resources, whose common destination is the U.S. and Mexico,” the document states.

Diquís: Clean Energy?

To date, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) has financed feasibility, environmental and social impact studies around the Diquís project. They explained their investment as “contributing to increased energy supply in Costa Rica and Central America, promoting sustainability, efficiency and competitiveness of the region’s energy sector, in order to address the impact of CAFTA (a “free trade” agreement between the United States, Central America and the Dominican Republic) in the region, through the implementation of a large-scale clean and renewable energy project.”

Archeological excavations in Broran territory. (Photo: Diquis Dam Archive)

Archeological excavations in Broran territory. (Photo: Diquis Dam Archive)

The Process Is Finalized

The process of developing a consultation protocol was designed by the government to occur in four phases and began in March 2016. Of the 24 Indigenous territories of Costa Rica, 20 agreed to everything up until the last phase, including the people of Térraba. Now, the president must issue an order legitimizing the consultation protocol for Costa Rica.

“We debated a long time over whether or not to participate in this process. We’re aware that the government always has political gains in mind,” said Broran. “We also know that they manipulate the term ‘consultation,’ that they’re trying to show good faith for public relations. But we want to be there, and say what we think, in front of all Costa Rica.”

The Bribri people of Talamanca, a territory in southern Costa Rica, refused to participate in the development of the consultation protocol. “This whole process is a performance,” Bribri tribe member Baudillo Salles Sánchez told Truthout. “Protocols and consultations are tools to justify entering and exploiting the territory. They do the consultation as they wish, and then they can say that they’re exploiting our resources with our consent.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.