Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

The following is an interview with Nelson A. Denis, the author of War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony.

Mark Karlin: The US government claimed it was liberating Puerto Rico from Spain in the Spanish-American War, but in 1898, then insisted that the island’s residents would never be independent. As soon as the island came under the control of the United States you document racist, military and economic interest rhetoric that justified US colonization. You quote The New York Times, at the time, as writing: “[I]t would be much better for her [Puerto Rico] to come at once under the beneficent sway of these United States than to engage in doubtful experiments of self-government.” Wasn’t the US engaged in the same colonial racism of Spain – that conquest was predicated on allegedly “taming the savages?”

Nelson A. Denis: In 1897, Spain granted Puerto Rico a Carta de Autonomia (Charter of Autonomy), which gave the island the right to its own legislature, constitution, tariffs, monetary system, treasury, judiciary, shipping industry, international trading rights and coastal control. All of this was rescinded when the US assumed “ownership” of Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory (ie, a possession) of the US, pursuant to the Treaty of Paris.

Since then, and continuing to this day, the US has denied all of the sovereign elements of the 1897 Carta de Autonomia. It lied to Puerto Ricans with respect to their de facto membership in American society: declaring them US citizens in 1917, then ruling that the US Constitution “did not apply” to Puerto Rico (Balzac v. Porto Rico, 1922) and, as such, the privileges and immunities of the US Constitution “did not exist” on the island, as an unincorporated territory.

What did this mean? It meant that from 1948 to 1957, under Public Law 53, Puerto Ricans could not utter one word, sing a song, whistle a tune, or communicate anything against the US government, or they’d be imprisoned for 10 years for “seditious conspiracy against the US.”

It meant that in the mid-1930s, when AFL-CIO president Samuel Gompers visited the island, he announced that, “Wages today are less than half what they were under the Spanish.”

It meant that, as opposed to the Spanish Charter of Autonomy of 1897, the US (to this day) controls all of Puerto Rico’s foreign relations, customs, immigration, postal system, communications, radio, television, commerce, transportation, social security, military service, maritime laws, banks, currency, judiciary, tariffs, trade relations, shipping industry and cabotage rights.

Spain would not have granted a Charter of Autonomy to “a nation of savages.” Spain recognized – and granted – the complete preparedness of Puerto Ricans to assume the management and destiny of their island. But then the US won their “Splendid Little War,” and manifest destiny arrived in Puerto Rico.

Can you detail some of the imperialist laws imposed on residents of Puerto Rico by the US, including only teaching English in schools and making display of the Puerto Rican flag illegal?

The US attempted to force every school child to speak English – and only English – in the public schools of Puerto Rico. The children and many parents resisted this so forcefully, that “English-only” was scaled back … then virtually eliminated in the Puerto Rico public schools.

In 1900, the US forced everyone to exchange their Puerto Rican currency for US dollars and devalued the Puerto Rican peso by 40 percent. Overnight, by legislative fiat, every Puerto Rican lost 40 percent of their savings, wealth and property. Farms went into immediate default all over the island. With no usury law restrictions, the American Colonial Bank engaged in island-wide predatory lending. By 1930, every sugar cane farm in Puerto Rico belonged to one of 41 syndicates, 80 percent of which were US owned.

In 1922, the US Supreme Court held that the US Constitution did not apply to Puerto Rico (Balzac v. Porto Rico). As such, any US minimum-wage legislation, or other federal protections, privileges and immunities, “did not apply” to Puerto Ricans on the island.

From 1948 to 1957, Public Law 53 (aka The Law of the Muzzle, La Ley de la Mordaza), eliminated the First Amendment in Puerto Rico. No one on the island could utter one word, sing a song, whistle a tune, or communicate anything against the US government, or they’d be imprisoned for 10 years for “seditious conspiracy against the US.”

In chapter one, you create a riveting account of an infamous prison, La Princesa, in San Juan and the conditions of advocates of independence incarcerated in horrendous conditions there. You end the chapter focusing on the squalid state of Pedro Albizu Campos, captured president of the Nationalist Party. The details you provide of the wretched conditions are remarkable. How did you research and document such a vivid picture of La Princesa and the imprisonment of Campos there?

There were multiple sources regarding La Princesa. For nearly 40 years, from 1974 until recently, I spoke with numerous ex-prisoners from La Princesa and other prisons. The FBI files (carpetas) contain thousands of pages which – inadvertently, but in great detail – provide much first-hand information about prison conditions and procedures in La Princesa.

A Nationalist prisoner named Heriberto Marin Torres also wrote a first-person account of his imprisonment after the 1950 revolution. He was imprisoned in El Oso Blanco in Rio Piedras, but he also wrote about La Princesa and the conditions in both prisons. The book was called Eran Ellos, and it is cited in my book (see footnote 4, page 270).

Another detailed account of conditions at La Princesa is found in the party filings, court transcripts, and court’s opinion in Martinez Rodriguez v. Jimenez. The jail was permanently shut down in 1976 as a result of this court case. The conditions in La Princesa were even more horrific in 1950, particularly for the Nationalist prisoners.

Campos was the first Puerto Rican to graduate from Harvard and Harvard Law School. He chose not to pursue a lucrative career in law but instead to organize and fight for the independence of his homeland. In the end, you document that he likely died from US government-inflicted radiation poisoning. Although you spend much of the book returning to him as your central historical figure, can you briefly summarize his journey to taking on the FBI and US military battling for a free Puerto Rico?

Pedro Albizu Campos was a brilliant man … the first Puerto Rican to attend Harvard College. The first to attend Harvard Law School, where he was the class valedictorian. He spoke six languages and helped Eamon de Valera to draft the Constitution of the Irish Free Republic.

As president of the Puerto Rico Nationalist Party, Albizu Campos organized, advocated, editorialized, spoke throughout South and Central America – but it was not until he hurt Wall Street in their collective pocketbook, that the US government paid any attention to him.

When Pedro Albizu Campos led an island-wide agricultural strike in January-February 1934, which succeeded in doubling the sugarcane workers’ wages from 75 cents a day to $1.50 per day, the US government immediately:

• Sent down US Army General Blanton Winship as the new governor of Puerto Rico;

• Sent down Col. E. Francis Riggs as the new Chief of Police;

• Winship and Riggs immediately militarized the entire Insular Police force with machine guns, grenades, riot gear and “tommy gun training”;

• FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent down hundreds of FBI agents to “collect intelligence” on Puerto Rican Nationalists – particularly Albizu Campos;

• Hoover ordered a secret FBI file program known as carpetas. Over a period of six decades (1930s-1990s) the FBI collected carpetas on over 100,000 Puerto Ricans, totaling over 1.8 million pages;

• Albizu Campos was jailed within 15 months of the agricultural strike in July 1936. He died in 1965.

During those 29 years, 25 of them were spent in prison. During the other 4 years, he was surrounded by a 6-man FBI agent detail – 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It required 25 FBI agents to maintain this 6-man rotation.

When Campos returned from prison in December 1947, Public Law 53 was passed in Puerto Rico. This “Gag Law,” as described above, abrogated the First Amendment rights of over 2 million Puerto Ricans, in order to shut one of them up (Albizu Campos).

All newspaper communications off the island were controlled by a handful of AP and UPI wire service reporters. There was no television, internet; and radio transmission from PR to the US was virtually nonexistent. Under these conditions, Albizu Campos realized that the only way to get word off island, about its true colonial existence, was to raise a revolution that could capture world attention. Winning was out of the question. The US had just pulverized Nagasaki and Hiroshima. But it was possible to model an uprising after the Easter Rising of 1916 in Ireland, which could make a powerful moral statement about how the US was treating this island.

For this reason, Albizu Campos and the Nationalists planned the October 1950 revolution. Even though this revolution included the bombing of two towns (Jayuya and Utuado) by 10 US P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes, the attempted assassination of President Harry Truman, and the arrest of 3,000 Puerto Ricans, President Truman dismissed it as “an incident between Puerto Ricans.”

The irony of all this, is that George Orwell published 1984 in 1948-49. It was an instant, international bestseller in the UK and US … at the same time that the US was running a totalitarian Orwellian colony in Puerto Rico.

The suppression of the Puerto Rican independence movement by the US, orchestrated in large part by Herbert Hoover, was massive, bloody and something akin to the actions of a police state. You quote World War I hero General Smedley Butler about his fighting in Latin America as writing, “I was a gangster for capitalism.” To what extent was Puerto Rico dominated by US corporations from its conquest by the US in 1898?

(For specific facts and figures about this, please refer to the bottom of page 254, top of page 255 in the book. Also pp. 29-31 and pp. 56-58.)

As early as 1931, historian and Yale professor Bailey W. Diffie wrote that “The sugar industry, tobacco manufacturing, fruit growing, banks, railroads, public utilities, steamship lines, and many lesser businesses are completely dominated by outside capital. The men who own the sugar corporations own both the US Bureau of Insular Affairs and the Legislature of Puerto Rico … practically every mile of public carrier railroad belongs to two companies – the American Railroad Company and the Ponce & Guayama Railroad Company … which are largely absentee owned … about half the towns depend on absentee companies for their lights and power, and more than half the telephone calls go over wires owned by outsiders … it is the absentee capitalist who makes the profit.” (See: Bailey W. Diffie and Justine Whitfield Diffie, Porto Rico: A Broken Pledge, New York: Vanguard Press, 1931, pp. 199-200.)

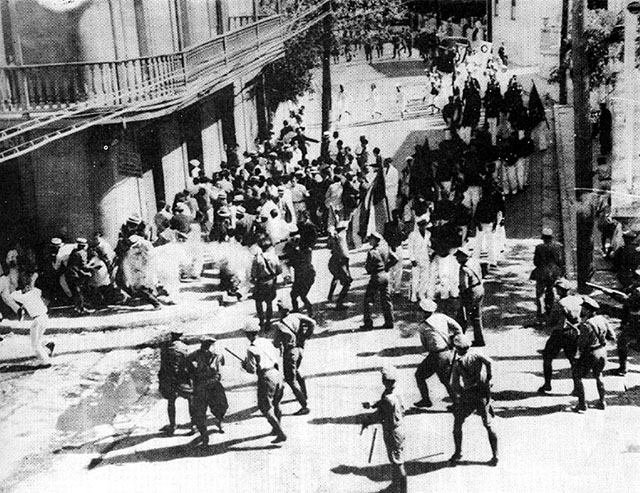

The Ponce Massacre begins. (Source: waragainstallpuertoricans.com)

The Ponce Massacre begins. (Source: waragainstallpuertoricans.com)

How did the evocation of the “Green Pope” in chapter 4 represent US business exploitation of Puerto Ricans, particularly in the sugar cane fields, but in all areas of commerce including even the railroads?

In the middle of page 58 of War Against All Puerto Ricans (Chapter 8) I identify Charles Herbert Allen, the very first US civilian governor of Puerto Rico, as the Green Pope.

If you read [John] Perkins’ Confessions of an Economic Hit Man, you will recognize the type. Charles Herbert Allen was the first US economic hit man to run amok in Puerto Rico. His first and only “Governor’s Report to the US President” was a naked, undisguised plan for economic exploitation of the entire island of Puerto Rico.

Pages 57-58 contain Allen’s specific language in this report:

“Porto Rico is really the ‘rich gate’ to future wealth … the yield of sugar per acre is greater than in any other country in the world … the cost of sugar production is $10 per ton cheaper than in Java, $11 cheaper than in Hawaii, $12 cheaper than in Cuba, $17 cheaper than in Egypt, $19 cheaper than in the British West Indies, and $47 cheaper than in Louisiana and Texas.”

(Additional racist and abusive language by Allen appears on pages 57-58.)

Within weeks of handing in this report Allen resigned his governorship, scurried up to Wall Street, and became a vice president of Morgan Guaranty Trust. He built the largest sugar syndicate in the world, and his hundreds of political appointees in Puerto Rico provided him with land grants, tax subsidies, water rights, railroad easements, foreclosure sales and favorable tariffs.

By 1907 Allen’s syndicate, the American Sugar Refining Company, owned or controlled 98 percent of the sugar-processing capacity in the US and was known as the sugar trust. By 1910, Allen was treasurer of the American Sugar Refining Company, by 1913 he was its president and by 1915 he sat on its board of directors. Today his company is known as Domino Sugar.

By 1934, every sugar cane farm in Puerto Rico belonged to 1 of 41 syndicates, 80 percent of which were US owned. The four largest syndicates were entirely US owned and covered over half the island’s arable land. These banks also owned the insular postal system, the entire coastal railroad, and San Juan’s international seaport.

As of 1950, the Pentagon controlled another 13 percent of the island.

(For a fuller discussion of US corporate domination/control, please see these 3 articles written by me: “When a Puerto Rican Wins the Powerball” and “How to End Puerto Rico’s Debt Right Now.”)

One of your two introductory quotes is from someone who emerges in your book, E. Francis Riggs, chief of police of Puerto Rico from 1933-36: “There will be war to the death against all Puerto Ricans.” I was thinking that the subtitle of the book – “Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony” – refers to the terror that the US government committed against those in Puerto Rico who were seeking independence.

The terror was manifested in many ways:

• The Rio Piedras Massacre (pp. 66, 121);

• The Ponce Massacre (pp. 43-54, 69);

• The Utuado Massacre (pp. 198-199);

• The bombing of Jayuya and Utuado (pp. 193-199);

• The arrest of 3,000 Puerto Ricans as “suspected Nationalists” (pp. 223-232);

• The “disappearance” of Nationalists (desaparecidos) throughout the island (pp. 67,103,130);

• The passage of Public Law 53 (Ley de la Mordaza, the Gag Law), which eliminated the First Amendment in Puerto Rico (utter one word, sing a song, whistle a tune, own a flag … 10 years imprisonment) (pp. 104-105, 128, 168-169);

• The carpetas program, under which secret FBI files were maintained on over 100,000 Puerto Ricans over a period of six decades (pp. 73-77);

• The torture of prisoners in Aguadilla, near Ramey Air Base (pp. 171-181);

• The inhuman prison conditions as La Princesa penitentiary, particularly for Nationalist prisoners (pp. 3-9, 247-251); and

• The prison torture and TBI (Total Body Irradiaton) of Pedro Albizu Campos (pp. 233-251).

What has been the history and importance of Puerto Rico as a strategic military location in the Caribbean?

Puerto Rico is strategically located between North and South America – the first major land mass that a Spanish galleon would encounter after a long and harrowing sea voyage.

Later in 1898, The New York Times recognized it as a valuable naval coaling (ie refueling) station, with “a commanding position between two continents.” (Amos K. Fiske, The New York Times, July 11, 1898, p.6)

By mid-20th century, the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station was the largest naval base in the world. Spread out over Vieques Island and the Puerto Rican mainland, it encompassed 32,000 acres, 3 harbors, 9 piers, 1,340 buildings, 110 miles of road, 42 miles of oceanfront, and an 11,000-foot runway. It housed 17,000 people and serviced up to 1,000 ships annually.

In addition, by World War II, Camp Santiago occupied 12,789 acres in Salinas. Ramey Air Base covered 3,796 acres in Aguadilla. Ramey was a major hemispheric base for the Strategic Air Command (SAC) with fighter jets, bombardier planes, guided missiles, radio jamming stations, and numerous “ancillary services,” some of which are discussed in War Against All Puerto Ricans (pp. 171-181).

Fort Buchanan had 4,500 acres in metropolitan San Juan, with its own pier facilities, ammunition storage areas, and a massive railroad network into San Juan Bay.

After World War II, the US Navy used the island of Vieques for target practice for seven decades – exploding 5 million pounds of ordnance per year.

At its height, the Pentagon controlled 13 percent of Puerto Rico’s land and operated five atomic missile bases. In addition to the major bases, there were over 100 medium and small military installations, training camps and radio stations.

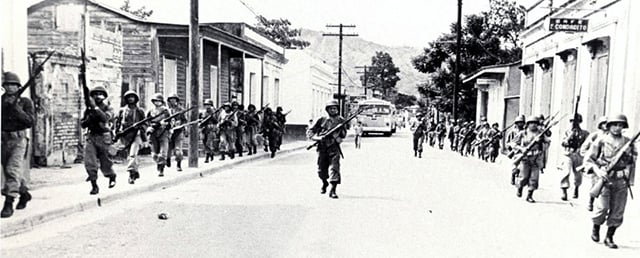

5,000 National Guard troops occupy the towns of Jayuya and Utuado. (Source: waragainstallpuertoricans.com)

5,000 National Guard troops occupy the towns of Jayuya and Utuado. (Source: waragainstallpuertoricans.com)

The continental United States expanded westward by massacring the indigenous population in the name of “Manifest Destiny.” I was once again struck in War Against All Puerto Ricans by the repeated assertions of racism toward island residents at the highest levels of US government. You quote President William Howard Taft as saying, “The whole hemisphere will be ours; in fact, as by virtue of our superiority of race, it already is ours morally.” You call this the “White Man Burden’s” syndrome. The US succeeded in “pacifying” Puerto Rico. None of the votes for independence or statehood has subsequently succeeded. Is there currently a viable nationalist movement on the island?

The Nationalist Party is not electorally active on the island right now, but the Puerto Rico Independence Party (PIP) has an increasingly attractive and sensible message, as well as leaders who are actually elected and sitting in the Puerto Rico Senate. A good example of this is Maria de Lourdes Santiago, who has been a member of the Puerto Rico Senate for the past 12 years, since 2004. If you understand Spanish, I encourage you to watch this interview on a public affairs progam called “Dossier.” It shows you the quality of leadership and vision, which is available in Puerto Rico. Here in Puerto Rico, both the Nationalist Party and the PIP have embraced my book. The Nationalist Party hosted a book event for me last night, which was attended by nearly 200 people. Here are some photos on my Facebook page. In July 2016, the PIP is creating a two-week tour for the book in 8 different towns throughout Puerto Rico. All of this reflects (as I wrote above) the growing consensus that the “Commonwealth” status is a disguised colonial fraud.

In your epilogue, you describe the economic conditions in Puerto Rico in 2015 as wretched in comparison to states on the mainland. Yet, it is only infrequently that you read about conditions on the island in the US corporate mainstream press. Why do you think that is the case?

I disagree. There are many recent articles in US corporate mainstream press about the Puerto Rican economy. Predictably, and often explicitly, they offer a common theme: that Puerto Ricans are incapable of managing their own affairs, and a US “intervention” will be required to straighten the mess out.

Most recently this “intervention” has taken the form of Act 22, which provides high-net-worth US investors with a 20-year tax exemption on all capital gains, interest and dividend income derived from their investments in the island. The prime beneficiaries of this tax giveaway are US billionaires such as John Paulson, who made $15 billion for his hedge fund by betting against the American economy and against the American homeowner, during the 2007 mortgage crisis.

Paulson is now leading the charge into Puerto Rico, buying up “distressed assets” all over the island, and leading a $500 million resort and condominium development in Dorado Beach.

Puerto Ricans are being subjected to gasoline tax hikes (two in the past year), skyrocketing water and electrical costs, a looming 11.5 percent sales tax (aka IVU), pension rollbacks, worker layoffs, water rationing, student tuition hikes, and small business tax hikes – in order to meet the interest payments (not even the capital payments – just the interest) on the $73 billion of public debt.

But Paulson and friends are receiving corporate welfare and tax havens of the highest order. The US business press are the carnival barkers for this economic freak show that is developing in Puerto Rico. They are extremely bullish on Puerto Rico tax-sheltered investments.

Given the corporate ownership of 90 percent of all US media, I would not be surprised if there were a high level of cross-ownership, undisclosed investments, and advertiser involvement behind many of these “authoritative” and “objective” pieces on Puerto Rico tax shelter opportunities for the superrich.

Here is an article I wrote on the subject, which contains multiple references (and links) to some of that business press – particularly near the end of the article: The History of Taxes in Puerto Rico

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 460 new monthly donors in the next 8 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.