On April 13, 2018, Emily Truitt, a dog groomer with a two-year old son, received a visitor at her doorstep. Responding to an accusation of neglect, an investigator with the Delaware Division of Family Services asked Truitt’s boyfriend for permission to enter their home while she was at work. This is a request millions of families receive each year, and though granting entry is not mandatory without a court order, many families — like Truitt’s — automatically comply.

Shortly after the investigator entered the home, Truitt says the investigator called to demand she leave work immediately to meet at the department’s local office. While there, Truitt, who takes methadone as part of her addiction recovery treatment, admitted to using marijuana daily for anxiety, and cocaine once in the week prior, but denied using illegal drugs in the presence of her child. After that admission, Truitt says, things went downhill fast.

“I saw she wrote I smoke around my son,” Truitt says of the safety plan her caseworker hand-wrote in pencil during their meeting. “I don’t smoke around my son…[My caseworker] said, ‘it’s the end of the day, we’re not changing it.’” (Due to confidentiality laws, the Delaware Division of Family Services declined to comment.)

Safety plans like these are widely used in the realm of child protective services investigations in an attempt to resolve perceived threats to a child’s health and safety without judicial involvement. Though informal, they are signed by both parties and are considered binding within the realm of the department. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, a positive drug test (or other confirmation of a single act of drug use) is not enough to substantiate child maltreatment accusations, or to determine child placement. But because safety plans are not legal documents, local departments have discretion of how they apply those standards, so long as the parent agrees and signs the plan. It’s up to the department what happens if a family violates an agreement, but the possibility includes showing up with a police officer and a court order to remove the child.

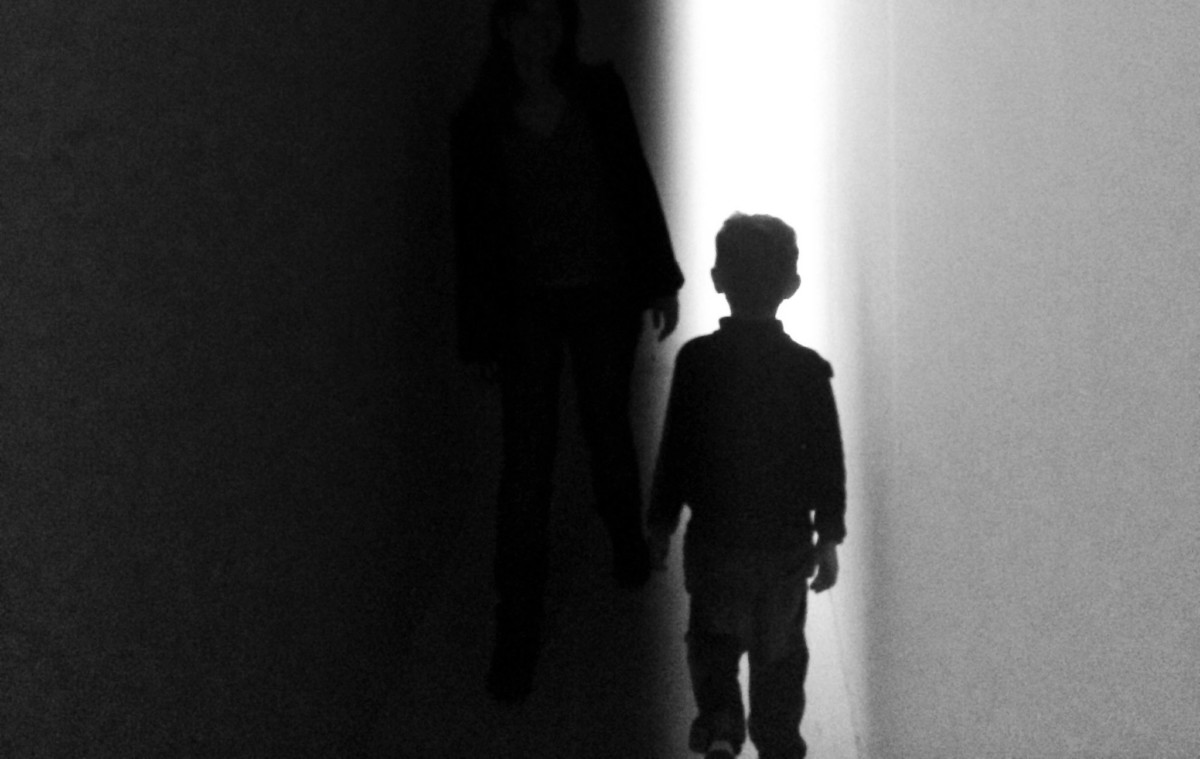

For Truitt and her family, this safety plan had devastating effects. As part of the plan, Truitt was asked to place her son in the care of a family member. She says she initially believed it was just for the weekend, but Truitt’s son ended up living with her sister for 30 days. Truitt says she signed the safety plan because she was told the alternative was foster care. What she didn’t know was that the department would have needed to present the case to a judge before placing her son in foster care. Agreeing to a safety plan is not compulsory, nor are these plans technically binding in a legal sense. But parents, who are often pressured to appear compliant, don’t always know this. If they can’t hire an attorney on their own, it’s unlikely anyone will tell them that they don’t have to agree.

Because child services agencies are regulated at the state and county levels, we have no way to gauge exactly how many families are separated through these methods: The only data is voluntary and self-reported. In one class-action lawsuit related to safety plan removals, a case that began in the 1990s and covered only the state of Illinois, there were more than 150,000 plaintiffs. Child removals have only risen since that time.

In 2016, child services agencies across the United States received maltreatment complaints for more than seven million children, with close to four million of those children deemed as meeting the initial criteria for abuse, abandonment, or neglect. At least one-fifth were removed from their parents’ care. Rachel Paletta, senior associate at the Center for the Study of Social Policy, says that “the majority of child protective services referrals are for child neglect, so that may be inadequate housing or lack of clothing and food, and all of these things can be related to poverty…[however,] circumstances that are solely a result of poverty and not ill intent on the part of the parents should not be considered neglect or abuse.” Although it’s difficult to place an exact figure on the amount of low-income families that have child welfare involvement, there does appear to be a correlation between child removals and families who require financial assistance.

Safety plans have become the subject of legal scrutiny in recent years, but thus far, attempts to curtail their use have failed. Opponents of safety plans cite their coercive nature — it’s hard to say that a parent is truly volunteering to the terms when the other option presented is long-term separation from their children. Of course, although case workers are advised (and in some states, mandated) to inform parents like Truitt about the possibility that their children will be removed for a longer time by a judge, it’s impossible for these workers to accurately predict the outcome of a hypothetical hearing — especially since the parent could have access to legal counsel and Child Services would be forced to present evidence of maltreatment.

Although their separation was relatively short, Truitt says her family is still suffering the effects. Her son, who will be three in August, constantly screams to be held, which she says is a new behavior. He cries whenever they visit her sister, and he has developed an intense phobia of bugs. Truitt thinks this is because they told him he was staying with his aunt due to an infestation in the home. She is now “constantly paranoid” that child services will try to remove her son without warning again, even though she is actively engaged in addiction and mental health treatment.

Maia Szalavitz, a neuroscience journalist and co-author of The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog: What Traumatized Children Can Teach Us About Loss, Love and Healing, says that even short-term parental separation can have devastating lifelong consequences for children.

“Every single time a child makes a custody transition it’s an adverse childhood experience so it’s potentially traumatic. The more of these experiences you have, the greater the risk for addiction, mental illness, and physical problems like obesity,” says Szalavitz. She also notes that this goes both ways; once a child adjusts to a new custodial environment and begins bonding with his new caregivers, returning home counts as a stressor. That means that every time a child is placed into temporary out-of-home custody, he is guaranteed at least two adverse experiences. For children bouncing between homes in the foster care system, the number of adverse childhood experiences caused by child services involvement is even higher. One study found that four or more adverse childhood experiences indicated a significantly increased likelihood of physical and mental health problems later in life.

For now, Truitt is happy to be reunited with her son. In the thick of the Delaware summer, she enjoys splashing with him in the kiddie pool she has set up in her backyard. But she remains haunted by the possibility that a social worker could come by once again and, with nothing but a pencil, uproot her family like they did last April.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.