Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

Needless to say, like many Americans, I am both delighted and cautious about Barack Obama’s election. Symbolically, this is an unprecedented moment in the fight against the legacy of racism while at the same time offering new possibilities for addressing how racism works in a post-Bush period. Politically, I think it puts the brakes on many authoritarian and anti-democratic tendencies operating both domestically and abroad, while offering a foothold not only for a fresh critique of neoliberal and neoconservative policies, but also an opportunity to reclaim and energize the language of the social contract and social democracy.

While the Bush administration may have been uninterested in critical ideas, debate and dialogue, it was almost rabid about destroying the economic, political and educational conditions that make them possible. In the end, the Bush administration was willing to sacrifice almost any remnant of democracy to further the interests of the rich and powerful, especially those commanded by corporate power.

The Obama administration will fail badly if it does not connect the current financial and credit crisis to the crisis of democracy and its poisonous undoing by commanding market forces. Corporate power, rather than simply deregulation, has to be addressed head-on if any of the ensuing reforms undertaken by the Obama administration are going to work. Similarly, the social state has to be resurrected once again against the power and interest of the corporate state; that battle is not just economic and political, but also pedagogical.

Of course, the last thing we need is to overly romanticize the Obama election. We don’t need lone heroes offering a path to salvation and hope. Obama’s victory is not about the gripping story of his personal journey and ultimate victory as a black man, but about the emergence of a certain moment in history when not only small differences matter, but new possibilities appear for making real claims on the promise of democracy to come. What this historic event should make clear is the necessity for various progressive and left-oriented groups to get beyond their isolated demands and form a powerful progressive movement that can push Obama to the left rather than allow him to drift to the center and right.

Of course, this means that progressives will have to do more than embrace a language of critique; they will also have to engage in a discourse of hope, but a hope that is concrete, rooted in real struggles, and capable of forging a new political imagination among a highly conservative and fractured polity. This is an especially important time for educators.

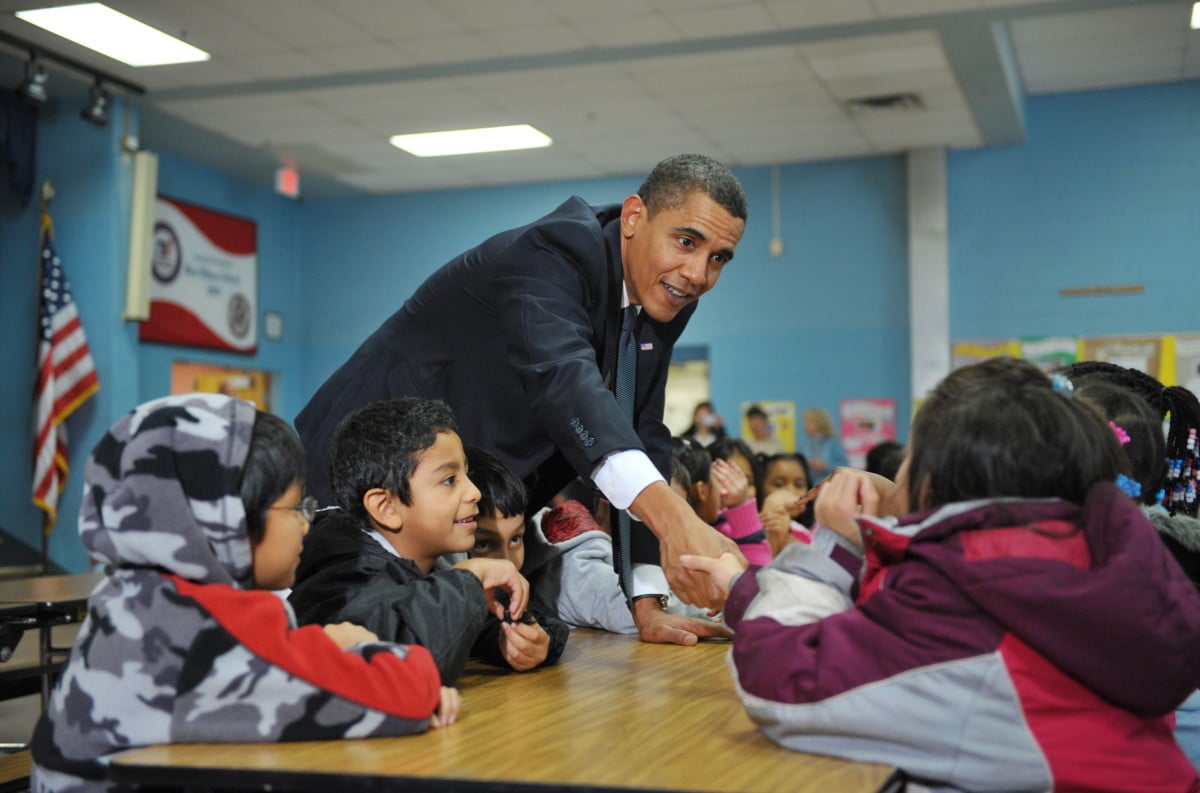

New York Times columnist Nicholas D. Kristof recently argued that one of the most remarkable things about this election is that Obama is a practicing intellectual and that the era of anti-intellectualism so pervasive under the Bush administration may be coming to an end. Surely a message that resonates with anyone interested in the power of ideas. But there is more at stake here than an appeal to thoughtfulness, critique and intelligence; there is also the need to rethink the relationship between education and politics, the production of particular kinds of agents as a condition of civic life, and the ways in which new and diverse sites of education in the new millennium have proliferated into one of the most powerful political spheres in history.

One of the most important challenges, especially for educators, facing the US in a post-Bush period, is to take seriously the educational force of a culture that is central to constructing a new type of citizen. What is needed are citizens defined less through the hatred and bigotry of racism and the narrow obligations of consumerism than through the values, identities and social relations of a democratic society.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.