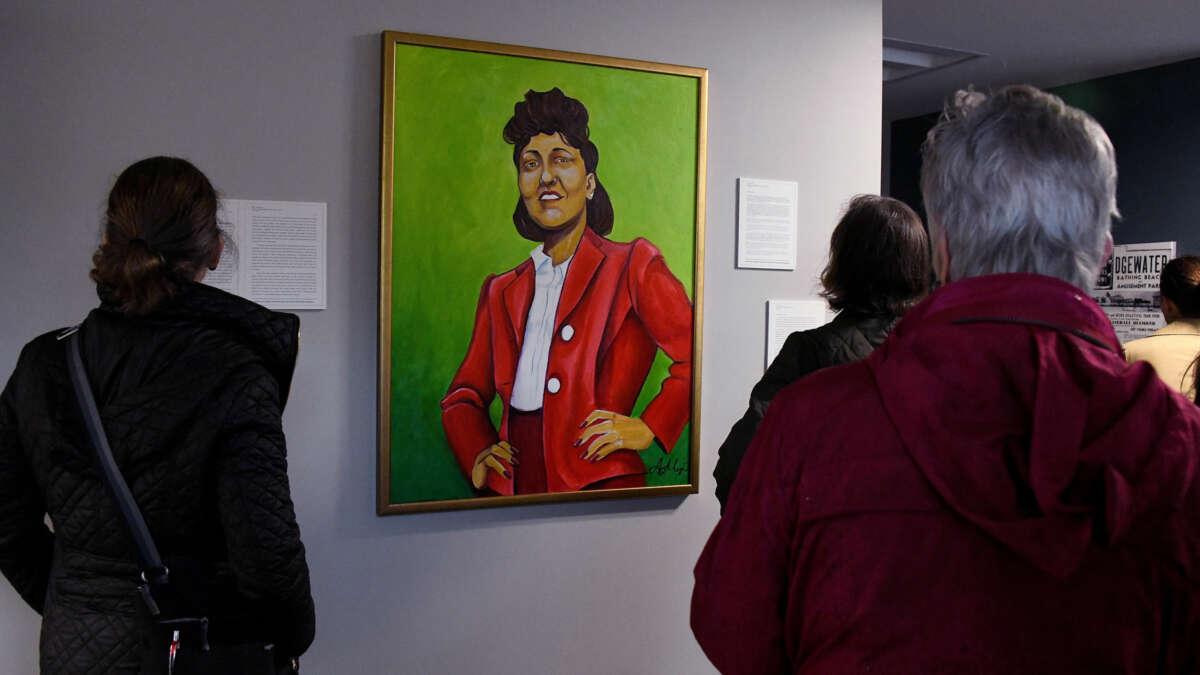

After a two-year legal battle against Biotech company Thermo Fisher Scientific, descendants of Henrietta Lacks won a settlement over the use of their relative’s DNA. Seventy years ago, Johns Hopkins Hospital removed tissue from Lacks’s cervix without her consent as she was dying of cervical cancer. Her cells, named HeLa after the first two letters of her first and last name, were the first human cells to be reproduced in a lab setting. Since then, medical teams have used and sold her cells for medical research to develop vaccines for COVID-19 and polio, and treatments for Parkinson’s and cancer. However, at the center of this discovery is an unequal medical and research system. The medical industry has historically used Black people for research without regard for their consent, dignity or compensation.

Lacks’s descendants had no knowledge of her cells’ revolutionary impact on medicine until more than 20 years after her death. Her descendants are proud that she has contributed so much to modern medicine; her cells were used in over 100,000 medical research papers. However, they are deeply upset by how she was treated by the hospital during her fight with cervical cancer. Lacks was hospitalized at the “colored ward” in Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she was then treated. Samples of tumorous tissue and healthy cervical tissue were taken without her consent. This sample of cells was then used for research, where they discovered Lacks’s cells’ unique ability to reproduce outside of her body. Usually, cells die outside the body. Unfortunately, Henrietta later died from her cancer in excruciating pain, leaving behind her husband and five children. However, her cell samples remained and became immortal.

At first, the Johns Hopkins doctor who discovered the cell’s groundbreaking abilities reproduced and distributed the cells for free to other researchers. Medical labs around the world used her cells for research. A few decades later, a factory mass-produced Lacks’s cells at a rate of 6 trillion cells a week. Biotech companies like Thermo Fisher Scientific could then obtain her cells for cutting-edge research and profit billions of dollars each year.

Beyond the astronomical profits that the medical establishment has made from Lacks’s cells, this has had a continuous impact on her family. Lacks’s only daughter who survived into adulthood, Deborah, worked to find crucial information about her mother’s cells for years. Henrietta died when Deborah was only 5 years old, and these cells are among the few parts of her mother that remain. Deborah confronted academic jargon, opaque medical systems and misinformation as she searched for the truth about the fate of her mother’s cells. Her family has struggled to assure that Lacks’s legacy is treated with dignity as medical institutions released her name, medical records and even her genome sequence without their consent (the genome was removed and later republished after working with her family.) Deborah herself, however, didn’t have medical insurance throughout her life to access some of the groundbreaking treatments that her mother’s cells helped develop.

This case of Henrietta Lacks’s cells unfortunately is a part of the grim history of medical research and its relationship with Black patients. Throughout U.S. history, Black people have contributed to medical research without their consent. Modern gynecology is based on the findings of J. Marion Sims, whose research was based on experiments done on enslaved Black women. With total disregard for their dignity and without the use of anesthesia, these women were subject to painful and invasive surgeries to examine their reproductive organs. The U.S. government in 1932 began a study on the effects of long-term syphilis on a population of 600 Black men by infecting 399 of the men with the disease. The Black men in the study were not told that they were intentionally infected as a part of the study. Even though penicillin was discovered as a treatment for syphilis, the study’s subjects themselves did not receive the treatment. The study ended in 1972, with 128 of the men dying of syphilis and/or related complications; 40 wives of infected men also being infected, and 19 children born with congenital syphilis. The gross ethical violation of this study helped establish the practice of informed consent and a stronger ethical code for research.

Deborah confronted academic jargon, opaque medical systems and misinformation as she searched for the truth about the fate of her mother’s cells.

This difficult history has had deep effects on Black people as we continue to confront the medical system. We are hyper-aware of systemic racism and exploitation that exist in health care. Cases like Henrietta Lacks and the Tuskegee Study highlight how medicine has continuously mistreated and profited from Black bodies with little consideration for their well-being, dignity and consent. The recent Netflix comedic fantasy film They Cloned Tyrone highlights this contentious relationship.

This distrust, unfortunately, reinforces already existing medical gaps for Black people. Black people are far less likely to participate in medical studies, which leads to biased data and treatment research. When Black people face discrimination in hospitals, we are hesitant to seek care again. Among white medical residents, over half believe that Black people experience less pain. This stereotype leads to mismanagement of patients and their traumatic experiences.

Even though the settlement for Lacks’s family is long overdue, much more is needed to confront ongoing medical racism. Acknowledgment — and compensation — are important steps for change, but the medical industry needs to address these enduring systemic inequalities. This requires a shift to inclusive medical education, research practices, patient relationships and access to insurance. The employment of Black doctors and other health care professionals is shown to positively affect patient health outcomes. Movements to address racial inequality in health care have made strides in recent years, as hospitals and other medical institutions are integrating best practices and racial inclusion education to address these ongoing disparities. As the fight for equitable health care continues, we must continue to push the medical system to address its past, and create a just future.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.