Ireland triumphs! Or maybe not.

There’s a visible push to claim that Ireland’s recent experience — somewhat better-than-expected growth in the second quarter and a rise in exports — vindicates austerity policies. There was even a new article in The Financial Times recently on export growth in Ireland, trumpeting a rise in pharmaceutical exports.

According to the report, published on Sept. 29, “IDA Ireland, the state agency tasked with attracting inward investment, says Ireland hosts eight of the world’s top 10 pharmaceutical companies, 15 of the top 25 medical device companies and seven of the world’s leading technology firms.”

So, some cold water. First of all, eventual recovery after years of Depression-level unemployment is a strange definition of success. But there’s also a specifically Irish twist. Pharma accounts for a large share of Irish exports — but it makes a much smaller contribution to the Irish economy.

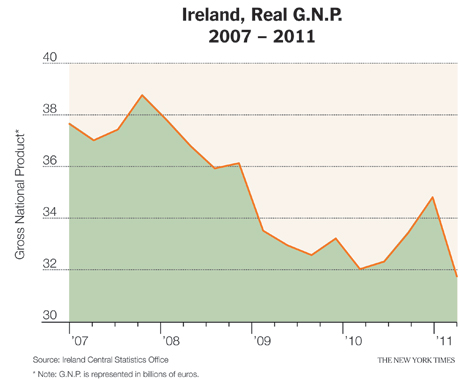

Partly that’s because pharma uses a lot of imported inputs, so that it has relatively low domestic content. Partly that’s because pharma is very capital-intensive, employing very few people — and the capital is foreign owned, so that the contribution to gross national product, which deducts income paid to foreigners, is smaller than the contribution to gross domestic product, which doesn’t. Indeed, Ireland is one of those countries where you really want to track G.N.P. rather than G.D.P. to get a sense of how the country is doing. The graphic on this page shows how it’s doing. Success!

To be fair, Ireland is doing a bit better than feared; it’s achieving a significant amount of “internal devaluation” via

deflation, which is leading investors to consider the possibility that it might actually avoid default.

I should also make clear that given its commitment to the euro, Ireland had to engage in some kind of austerity program, although it wouldn’t have been as draconian if not for the decision to socialize all of the banks’ debts.

Math Is Hard, Euro Edition

It’s astonishing how many European officials and unofficial wise men insist, with a great air of wisdom, that the euro crisis was caused by failure to enforce the stability pact — that is, limits on deficits and debt.

How hard is it to look at the data and discover that Ireland and Spain appeared to be fiscal paragons on the eve of the crisis, with budget surpluses and low debt?

Yet another triumph of the Very Serious narrative over easily checked facts.

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Paul Krugman joined The New York Times in 1999 as a columnist on the Op-Ed page and continues as a professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. He was awarded the Nobel in economic science in 2008.

Mr Krugman is the author or editor of 20 books and more than 200 papers in professional journals and edited volumes, including “The Return of Depression Economics” (2008) and “The Conscience of a Liberal” (2007). Copyright 2011 The New York Times.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.