Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

At the climax of Dear White People, a minstrel-style house party, complete with white students wearing blackface, causes what the media call a “race war” at elite Winchester University. At the film’s heart, however, all the main characters who are black are masking, too. These black students slowly – though perhaps not consciously – recognize that they’ve joined the ranks of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We,” which includes generations of African-Americans who “wear the mask that grins and lies.”

Though the black students do not wear the mask of racial mimicry and appropriation associated with minstrels, they do wear the mask of acceptability, of moderation, of, even, whiteness (and, even, blackness). Both masks, the ones worn by white students parodying black people and the ones worn by black students to appear less threatening, are worn at Winchester. And, in the film, Winchester is a microcosmic symbol of the United States, of white privilege in America, of the persistence of racism also at the heart – in the hearts of Americans.

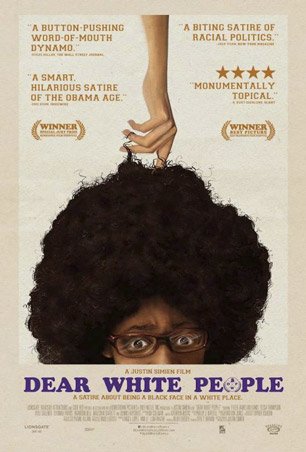

Directed by Justin Simien and starring the superb Tessa Thompson, Dear White People has benefitted from a smart online campaign that equals, if not exceeds, the talent of edgy sketch comedies like “Saturday Night Live” and “Chappelle’s Show.” Presented as “The More You Know PSAs” and State Farm-style “Racism Insurance” ads, Dear White People online examines everyday encounters between white and black Americans with fact-based lessons on how white folk can check their own racism. Crossing the vast minefield that still separates black and white in this country is a task Simien does well, even when black and white are joined in one brown body.

Thompson plays mixed-race Sam, host of an on-campus radio show, aspiring filmmaker and reluctant leader of black students seeking power over their residence hall at Winchester. That she is often afraid, unsure and nervous when speaking in front of groups makes her fearless confidence when positioned behind a microphone more powerful. Like all her peers at Winchester, Sam is fast-thinking, fast-talking and poised. Also like her peers, she is a young person coming of age within the gates of an institution ill-equipped to nurture diverse students of promise into the leadership roles their Ivy League educations should ensure.

Perhaps those closest to the institution, the two sons of Winchester administrators, one black, one white, best prove this point. That the most privileged of each race remains most handicapped by his father’s legacy at Winchester speaks volumes about the failure of all US institutions to bring out the best in all Americans. Black students, including the dean’s son, Troy Fairbanks (Brandon P. Bell), survive, even manage to thrive despite – and not because of – the inept adults at Winchester. The most privileged young white male of all, Kurt Fletcher (Kyle Gallner), is brash and popular, but also indecisive, unimaginative and more than a little bit dangerous – all a consequence of his inherited status as the son of Winchester’s president.

Please Note: Spoiler Alert (Below)

Just as the film examines the black-white binary with stunningly fresh intelligence, Dear White People also examines sexual orientation and the extra burden members of the LGBTQ community who are also black must shoulder. Lionel Higgins, played by Tyler James Williams of “Everybody Hates Chris” fame, experiences violence in nearly every scene he occupies. Unable to cope with racism in the gay community and afraid of homophobia in the black community, Lionel is ostracized and fetishized, sometimes simultaneously. Marginalized, objectified, voiceless, friendless, his physical assault in the party scene is just a new form of the emotional and psychological punishment he receives for simply existing. Lionel gathers allies, though, so his eventual victory is both a welcome relief and completely believable.

Dear White People is a skillful film. References to other films and filmmakers only enhance the audience’s appreciation for the level of craft it achieves. The casting choice of Dennis Haysbert (the real-life voice and face of Allstate Insurance) as Troy’s father is just one of many winks Simien gives that link his online campaign with the feature film.

Much of what works in the film is subtle, even sublime. Filled with arresting images and powerful scenes of microaggressions and racial bias, the feature narrative goes well beyond merely shocking the audience, as Sam’s white lover Gabe (Justin Dobies) urges her to do after she screens her reinterpretation of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in class. Gabe tells Sam to hold up a mirror to the school community, and she does, earning her film within the film much deserved and resounding applause.

Sam’s student film unmasks the hip-hop house party and reveals a horror show, with drunken participants simultaneously mocking authentic black culture and painful black subjugation while exploiting racist stereotypes to titillate and “eat the other.” That these horror shows go on, especially during Halloween, on college campuses all around the country, only magnetizes the full extent of the macabre aspects of eating and regurgitating blackness. Dear White People unmasks this horror and the ghouls that produce it.

The film also unmasks the black characters who seek inclusion. Sam desires inclusion among her fellow black students, but is slowly able to literally and figuratively let down her hair and fully express not only the white half of her biracial identity, but also her deep and mutual love affair with a white student. Their public expression of a private love, a simple gesture of hand-holding, is one of the most poignant moments in the film.

The other important female character, Colandrea “Coco” Conners, played by the irresistible Teyonah Parris, literally and figuratively removes the blond wig that symbolizes her desire for white privilege and also hinders her expression of personal (black) power. Her cool strength through most of Dear White People is a mask, and, when the film concludes, she emerges even more powerful, fully capable of verbally challenging Troy and, despite the status he inherits from his daddy, preventing him from reducing her to the category of side chick or fling.

It was time for a young black filmmaker to update Spike Lee’s School Daze and Bamboozled. With great attention paid to black female intersectionality and open examinations of black LGBTQ life, Justin Simien explores a great multiplicity of identities and the afro-surreal experience of being black and submerged in whiteness.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.