Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working Class Struggle

Edited by the Graphic History Collective, with a preface by Paul Buhle

Between the Lines Press, 2016

Howard Zinn once wrote that “to be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage and kindness.” It’s also more than this. As the Graphic History Collective, editors of Drawn to Change — a graphic depiction of numerous Canadian labor battles waged since the 1880s — note, “hope is critical to struggles for social change.”

Indeed it is, and the nine full-length, if short, comic books that comprise this anthology are exuberantly optimistic — even though many of the campaigns described in the collection actually sputtered or failed. Nonetheless, the intrepid spirit of those who imagined a more humane world is inspiring and offers a cogent push to the world’s workers, urging us to follow their bold example and take risks to improve our lot.

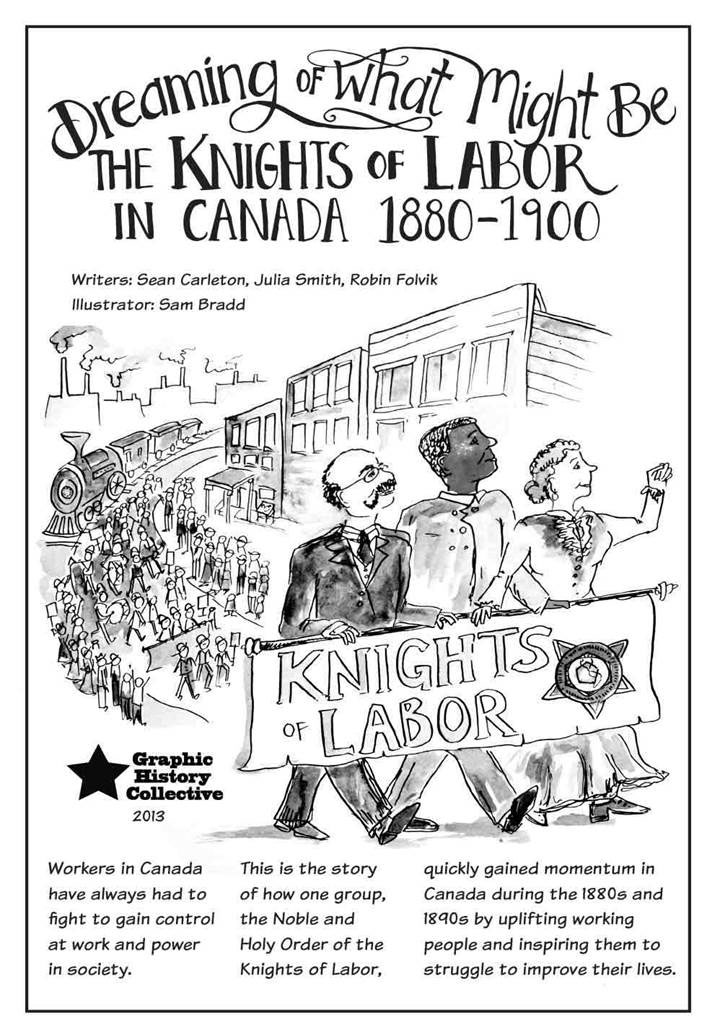

The book opens with Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labor in Canada 1880-1900, written by Sean Carleton, Julia Smith and Robin Folvik and illustrated by Sam Bradd. A brief written narrative introduces the artistic panels and provides an overview of the militant — and racist — Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor (KOL), “a secular brotherhood and sisterhood” that ran its own courts to punish perceived wrongdoings committed by members, from the “abuse of women, children, and workmates, to defrauding or stealing from fellow Knights of Labor, to exposing the secret, ritualized, inner workings of the Noble and Holy Order to non-members.”

Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labor in Canada, 1880-1900. Illustrated by Sam Bradd. Co-written by Sean Carleton, Julia Smith and Robin Folvik. Click to open larger in a new window.

Dreaming of What Might Be: The Knights of Labor in Canada, 1880-1900. Illustrated by Sam Bradd. Co-written by Sean Carleton, Julia Smith and Robin Folvik. Click to open larger in a new window.

KOL’s broad sweep involved the fostering of working class solidarity through social events, such as dances and picnics, and the publication of pro-worker newspapers, pamphlets and books. All told, the KOL provided a startling example of vision and activist breadth. This makes it absolutely horrifying to learn that the organization supported racial segregation, including the exclusion of Chinese immigrants. Still, the fact that Drawn to Change highlights this enormous political wrong, while simultaneously championing KOL’s many strengths, gives this section of the book nuance and connects it to modern-day xenophobia.

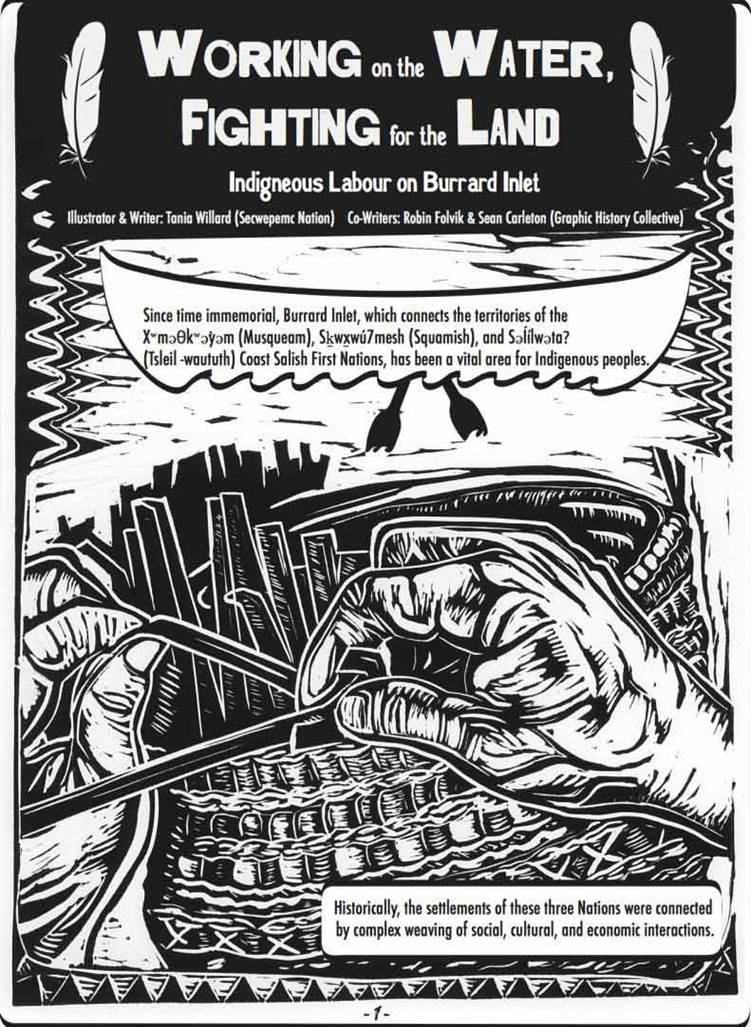

Similarly, the racist conquest of Vancouver Island by the British Crown, and Britain’s subsequent refusal to compensate native people for the land and resources it stole, is illustrated in Tania Willard’s linoleum-print drawings. In Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land, Willard and co-writers Carleton and Folvik depict the friction between indigenous Canadians — among them the Coast Salish, Musqueam and Squamish people — and the English-owned timber companies that became the region’s major employer in the early years of the 20th century. Beginning in 1959, the authors write, the Crown “claimed” a great deal of land and hastily set up new industries to profit from the rich resources they had access to. Although the land-grab rankled many native peoples, the lure of jobs proved irresistible. “The Squamish became an indispensable part of labour [sic] in the new industry,” the authors write. “Some worked as loggers, but many more worked as stevedores or longshoremen, leading the lumber into the tall-masted sailing ships that took the lumber to Pacific and European markets.”

Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet. Illustrated by Tania Willard (Secwepemc Nation). Co-written by Robin Folvik and Sean Carleton. Click to open larger in a new window.

Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet. Illustrated by Tania Willard (Secwepemc Nation). Co-written by Robin Folvik and Sean Carleton. Click to open larger in a new window.

Although the work was plentiful, it was not without difficulty, and the comic book notes that Squamish longshoremen faced relentless prejudice and discrimination. This prompted about 60 native lumber handlers and waterfront workers to form the Bows and Arrows, Local 526 of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1906. The Bows and Arrows worked tirelessly to bring attention to two issues: The horrid racism on the job and “the injustice of British Columbia’s land policy, specifically the lack of treaties.” The upshot, they conclude, was that in addition to fighting for bread-and-butter unionism, “native Canadians worked on the water to fight for the land.” Several violent strikes took place — notably in 1923, 1935 and 1945 — and the battles are far from over. Unfortunately, the comic offers scant details; nonetheless, it reports that indigenous people — on the docks and in communities — have taken this struggle into the 21st century as they fight for improved working conditions, better wages and policies that will protect the environment from further degradation.

From the Sea to the Mountains

Nicole Marie Burton’s Coal Mountain — the text and illustrations are both hers — looks at the abominable working conditions in the company-run Canadian coal town of Corbin, British Columbia, during the first decades of the last century. The efforts of the independent and radical Corbin Miners Association led to a bitter 1935 confrontation between workers and bosses that culminated in a long strike. The health and safety violations endemic to the mines were but one of their grievances. In fact, Burton notes that the workers complained that “the housing conditions in Corbin are unbearable for anybody to live in. Some instances the snow blows in through the cracks in the walls, through the window sashes and doors. We have repeatedly taken this up with management for the past three years but very little repair work has been done by the company.” In response, the owners cut off electricity to the dwellings that, in turn, caused the miners and their families to ramp up their fight. But despite financial support from other unions, the battle was made more difficult by management’s use of police-protected scabs. The ensuing clashes left 51 union picketers with either broken feet or head injuries.

Ultimately, the workers were outgunned — literally — and later that year, the mine shut down. Sadly, the workers had little choice but to search for new jobs in unfamiliar locales. It’s a terrible denouement.

That said, labor historian Ron Verzuh, in an introduction to the comic, writes that “by revisiting the tragic events of 1935, we can take a graphic tour of their struggle and witness the courageous actions of the men and women of this company town eighty years ago. Thanks to [Nicole Marie] Burton, Corbin takes its proper place in labour [sic] history as a symbol of resistance to oppressive employers everywhere.”

This is undoubtedly true. Still, readers and activists also need to learn about successful campaigns and organizing progress. Thankfully, a comic called Kwentong Bayan: Labour of Love by Althea Balmes and Jo Alcampo offers a hearty dollop. The comic chronicles the ongoing efforts of Toronto’s Filipina and Jamaican nannies and caregivers to protect their jobs and better their working conditions. Like Domestic Workers United in the US, Canadian domestic laborers have begun to mobilize for higher wages, protections against sexual harassment, time off and other benefits. The graphic looks at the solidarity they’ve forged as they trumpet their demands. It also presents the incremental victories they’ve won, including passage of the Juana Tejada Law, which makes it easier for caregivers to establish permanent residency as immigrants to Canada.

Kwentong Bayan: Labour of Love. By Althea Balmes and Jo SiMalaya Alcampo. Click to open larger in a new window.

Kwentong Bayan: Labour of Love. By Althea Balmes and Jo SiMalaya Alcampo. Click to open larger in a new window.

Of course, short comics like those included in this collection — unlike full-length graphics like Maus or Persepolis, for example — cannot provide a comprehensive history of complex labor conflicts, whether in homes, offices, mines or on the waterfront. But to its credit, the Graphic History Collective provides readers with a long list of articles, books and films to supplement these concise, if appealing and provocative accounts, two of which highlight the courageous example of individual labor activists Madeleine Parent and Bill Williamson.

Bill Williamson. Illustrated and edited by Kara Sievewright. Click to open larger in a new window.

Bill Williamson. Illustrated and edited by Kara Sievewright. Click to open larger in a new window.

As I read about their bravery and chutzpah, I found myself thinking about my own union, the Professional Staff Congress of the City University of New York, and imagining ways to increase our visibility and solicit wider community support as we oppose tuition hikes and the push to privatize.

Drawn to Change offers a timely reminder that if we venture nothing, we will gain nothing. The text makes this point incredibly clear. Moreover, unless we fuse hope with action, we stand no chance of winning anything, either electorally or in the workplace.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 379 new monthly donors in the next 6 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.