Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

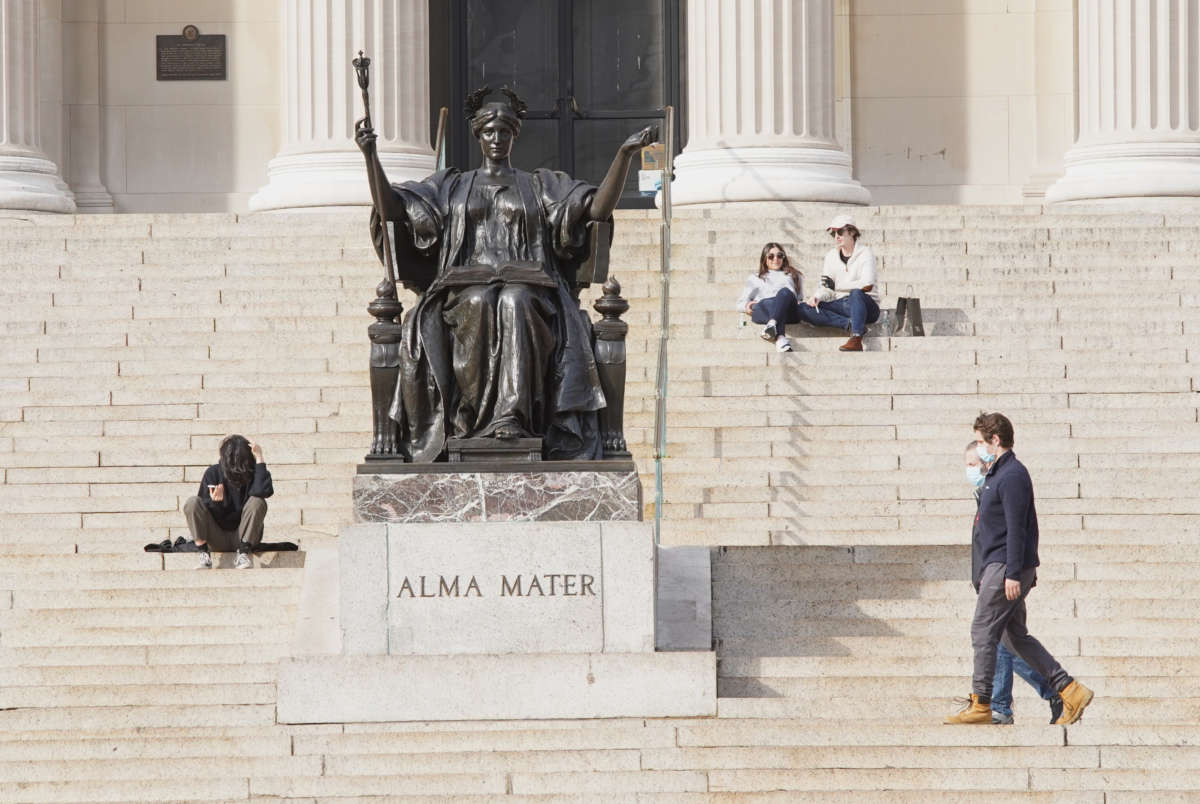

At the end of November, members of the Columbia University-Barnard College chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) launched a tuition strike campaign against “exorbitant tuition rates” which, they say, “constitute a significant source of financial hardship” during the pandemic. Student demands are wide-ranging and include a 10% reduction in the cost of attendance, 10% increase in financial aid, and an amalgamation of demands from disparate student campaigns, many of which were set in motion long before the pandemic began. So far over 1,700 students have signed a petition to withhold tuition for the Spring 2021 semester and any future donations to the university after graduating.

Columbia has consistently topped charts as the most expensive private university in the country, charging over $61,000 a year in tuition and fees, which accounts for nearly a quarter of the school’s revenue. “We just felt like the only way to pressure a university that is structured around the profit motive would be to directly impact their bottom line,” says Emmaline Bennett, a student at Columbia’s Teachers College and one of the founding members of Columbia-Barnard YDSA, which she co-chairs.

Since the pandemic began, the university’s $11 billion endowment has seen a $310 million increase while the response from administration, Bennett says, “has been mostly empty rhetoric around shared sacrifice.”

In These Times reached out to the university administration and did not hear back by the time of publication. In a December 1 article in Patch, a university spokesperson said, “Throughout this difficult year, Columbia has remained focused on preserving the health and safety of our community, fulfilling our commitment to anti-racism, providing the education sought by our students, and continuing the scientific and other research needed to overcome society’s serious challenges.”

Becca Roskill, a junior in Columbia’s school of engineering and secretary of Columbia-Barnard YDSA, says that the campaign has been careful to frame the tuition strike as a means of addressing the ongoing student debt crisis and not just worsening conditions under Covid-19. “We wanted to shift the conversation away from paying less because of online classes and shift the conversation toward a crisis that’s emerged from the fact that we’re treating education as a commodity in the first place.”

Leading up to the strike’s announcement, students organized a petition for partial tuition reimbursement (different from the one listed above), an email campaign and phone zaps, a pressure tactic used to flood office lines, to impress upon administrators the burdens of the university’s excessive costs. Before the start of the Fall semester, a tuition freeze was issued for the university’s two main undergraduate schools, Columbia College and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science — concessions that Bennett believes were a direct response to student organizing over the summer. But support for students and workers across campus, Bennett says, has been uneven, and the tuition strike is aimed at much more than just high tuition.

In addition to lowering the cost of attendance and increasing financial aid, the tuition strike has included demands to put an end to campus expansion, invest in the surrounding West Harlem community, defund the university’s Department of Public Safety (the campus law enforcement body), commit to transparency around the university’s financial investments, and bargain in good faith with unions on campus.

“The students organizing the tuition strike view it as a last-resort tactic to compel the university to listen to demands that students have been organizing around for the past few years,” reads a statement released Monday. The tuition strike has received wide support in part by building coalitions with other groups on campus that have put forward their own demands in the past. This includes referendums voted on by the student body, which the demands letter says should be respected and enforced.

A referendum that was passed in September demanding the university divest from companies that profit from or support Israel’s human rights abuses against Palestinians was the culmination of years of organizing from members of Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace. The referendum has been all but dismissed by the administration despite being passed by the student body. Similarly, administrators have been slow to respond to student demands to divest the school’s endowment from fossil fuels, a campaign that has been waged on campus since 2015. YDSA has been busy building ties with the campus chapters of Extinction Rebellion and the Sunrise Movement.

The tuition strike has also included demands from Mobilized African Diaspora (MAD), a coalition of Black student activists on campus that sent its own detailed list of demands to Columbia President Lee Bollinger. After spending the summer mobilizing against police violence, MAD called for the university to commit to anti-racism and provide employment and affordable housing to the surrounding Harlem community, end the university’s relationship with the New York Police Department, cut funding from the university’s Department of Public Safety and increase support for Black students.

On December 3, mere days after the strike’s announcement, Barnard College canceled its search for a new executive director of Public Safety and announced it would restructure the office to focus on community safety under the new Community Accountability, Response, and Emergency Services office. Bennett says MAD has been a major coalition partner, and the group’s demands to repair harm to the surrounding community and invest in community safety solutions are reflected in the tuition strike.

YDSA’s letter to the administration also includes a demand to bargain in good faith with unions on campus for increased benefits and compensation in addition to protections for international students. Statements from the tuition strike campaign have emphasized that cuts to cost of attendance “should not come at the expense of instructor or worker pay, but rather at the expense of bloated administrative salaries, expansion projects, and other expenses that don’t benefit students and workers.”

The Graduate Workers of Columbia-United Auto Workers Local 2110 (GWC-UAW), which has been the recipient of strike support and solidarity from YDSA, will be asking its membership to pledge their support for the strike. This would include distributing tuition strike materials to students and continuing to teach students who plan on withholding tuition even if told not to by university officials.

Susannah Glickman, a fifth year PhD student in history at Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and a member of GWC’s bargaining committee, says YDSA and the union have been working closely to support each other. “It’s good that students recognize that they have some power to influence the conversation [around corporate governance], even if they’re not employees,” Glickman said. “They probably have more [power] because they’re the financial base of the university.”

Tuition strike organizers say the idea for a tuition strike preceded the pandemic, but was in part inspired by the University of Chicago where 200 students withheld payments in late April with a number of demands, including a 50% reduction in tuition. By the end of their tuition strike in mid-May, University of Chicago students had won a freeze on tuition, which is now over $57,000 a year — second only to Columbia. Today, the total cost of attendance at the University of Chicago is estimated to be upwards of $80,000 a year when including fees, room and board, personal expenses and books.

With over 1,700 students signed on, Columbia’s tuition strike next spring could represent the largest tuition strike since 1973, when students at the University of Michigan withheld payments in opposition to a 24% increase in tuition from the year before. About 2,500 signed up for a tuition strike which coincided with a wave of labor organizing on the part of teaching fellows and other graduate employees. While the student tuition strike alone was not enough to win concessions from the University of Michigan’s administration, the Graduate Employees’ Organization (GEO), which represents graduate workers on campus, was ultimately able to win a tuition reduction and increased pay and benefits through contract negotiations after more than half of undergraduate students joined GEO members in a picket line in February 1975.

As students continue to mobilize toward next semester’s tuition strike, YDSA organizers report an increase in membership and participation within their chapter, which some believe has been strengthened by their ability to organize digitally.

“I think we’ve seen a strengthening in our community that we didn’t expect to be able to cater to over Zoom,” says Roskill. ”And we’re really hopeful that socialist politics will provide an answer to the political questions that weren’t being answered by Biden or Trump, particularly on student debt advocacy.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.