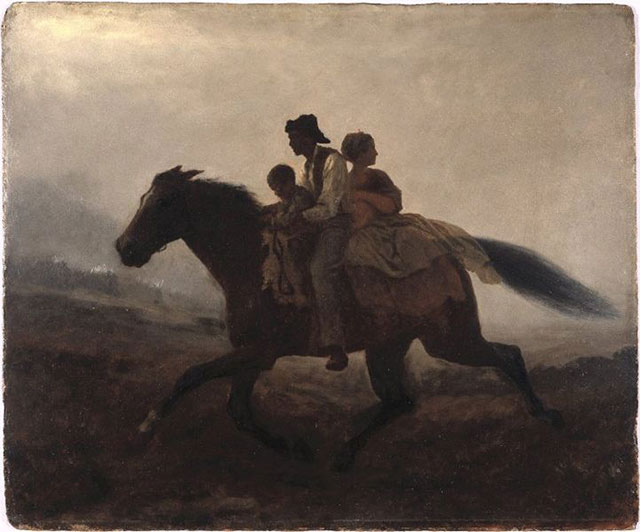

What is the price of freedom? During American slavery, Margaret Garner killed her child to save her from brutality. Runaways left family behind. Nat Turner and his rebels slaughtered their owners, only to be hung in turn. Every path of escape came with a price. How does one represent this terrible question in art?

Colson Whitehead’s sixth novel The Underground Railroad, coils the question tight and springs it. Every scene is propelled by the hunger for freedom or fear of it. At the center is Cora, an enslaved woman fleeing a Georgian plantation, and Ridgeway, a grim, infamous slave catcher who chases her. The ensuing hunt becomes an odyssey through a twisted American landscape.

Colson Whitehead. (Photo: Doubleday)At first, this novel seems an odd turn for Whitehead. He is known for high-end, conceptual and surreal work like 1999’s The Intuitionist or 2011’s zombie epic, Zone One, as well as the coming-of-age story about Black middle class life, Sag Harbor. None of his work prepares us for the bleak but near biblical prose driving The Underground Railroad, until you get to the central conceit. Whitehead reimagines the underground railroad (an above-ground network of safe houses) as a literal railroad with ramshackle trains chugging through dark tunnels, whisking escaped slaves to freedom. It is a dizzying choice that continues the vital literary tradition of Black magical realism.

Colson Whitehead. (Photo: Doubleday)At first, this novel seems an odd turn for Whitehead. He is known for high-end, conceptual and surreal work like 1999’s The Intuitionist or 2011’s zombie epic, Zone One, as well as the coming-of-age story about Black middle class life, Sag Harbor. None of his work prepares us for the bleak but near biblical prose driving The Underground Railroad, until you get to the central conceit. Whitehead reimagines the underground railroad (an above-ground network of safe houses) as a literal railroad with ramshackle trains chugging through dark tunnels, whisking escaped slaves to freedom. It is a dizzying choice that continues the vital literary tradition of Black magical realism.

Faced with modern racial violence, whether lynching or police shootings, Black authors have explored the history of slavery to understand the present. Yet many forgo the social realist mode and use the techniques of magic realism, where fantastic or mythical experiences are folded into the narrative as a seamless part of reality. Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison did so in her epic 1988 novel Beloved, in which a mother’s dead child returns as a fully grown woman. Ishmael Reed, in a comical vein, mashes up time in his 1976 satire, Flight to Canada. Charles Johnson invokes sorcery in his 1990 novel Middle Passage. Whitehead inherited this legacy, saying in a 2016 New York Times interview, “I went back and reread 100 Years of Solitude, and it made me think about what it would be like if I didn’t turn the dial up to 10, but kept the fantasy much more matter-of-fact.”

When Cora is guided by an abolitionist to the underground railroad, she is astounded to step into this netherworld of moving freedom. “The black mouths of the tunnel opened up at either end,” Whitehead writes, “Two steel rails ran the visible length of the tunnel, pinned into dirt by wooden crossties.” His use of a literal railroad becomes a symbol for the ambiguous state of liberty for Black bodies surviving state-sponsored racial terrorism. Cora and her companion Caesar are torn between hope and fear, wondering where the train will take them. Lumbly, one of the station managers, gives an answer that is a description of the dangerous limbo world of newly won freedom. “Locals, expresses, what station’s closed down, where they’re extending the heading,” he tells Cora, “The problem is one destination may be more to your liking than another. Stations are discovered, lines discontinued. You won’t know what awaits you until you pull in.”

Passages like that one are the gift of Black magical realism. In using fantasy to distill from reality its internal structure and render this structure visible through fantastic, even mythic imagery, Whitehead gives us a deep x-ray of America. It is why this novel, more than any he’s written before, seems so oddly prescient of our reactionary, post-Trump victory times. Each stop of this underground railroad is less a geographical space than a “Twilight Zone” episode where political ideologies are put into full, horrifying practice. Cora and Caesar experience the spectrum of white supremacy — from liberal to genocidal — until Cora finally escapes to a free, Black-owned space. The price of freedom changes with each locale.

When Cora and Caesar get to South Carolina, it boasts clean dorms and work and pay. Yet Cora finds the liberal refuge comes at the price of her humanity. Working at the local museum’s slavery exhibit, she acts the part of a slave. Her real memories clash against the liberal clichés, meant to appease a white sentimental gaze. Tired of being an object, Cora throws hate stares at visitors. “She picked the weak links out of the crowd, the ones who broke under her gaze,” Whitehead writes. The scene becomes a mirror to white fascination with movies like 12 Years a Slave and series like The Underground, which slake an endless liberal thirst for Black bodies as objects of pity.

Soon, Ridgeway, the slave catcher, arrives in town to capture them. She runs to North Carolina, where the price of freedom is invisibility. Cora hides abolitionists’ homes because, if found, she won’t be re-enslaved but lynched. North Carolinians, uneasy with the number of Black people within the state and the slave revolts in other states, replaced slaves with white workers. They expelled Black people and any that were caught were killed. “The corpses hung from trees as rotting ornaments,” Whitehead unflinchingly narrates, “Some of them were naked, others partially clothed, the trousers black where their bowels emptied when their neck snapped.” Black magical realism reflects in near hallucinatory prose the holocaust horizon of reactionary ideology. The scene of Cora peering from the window to a racist mob below echoes both the famous slave narrative by Harriet Jacobs and Anne Frank’s memoir of hiding from Nazis.

Truthout Progressive Pick

This award-winning novel tells the story of Cora, a young Black woman attempting to escape slavery in the antebellum South.

Click here now to get the book!

Cora escapes to a mini-utopia called Valentine’s Farm. The founder is a light-skinned man of means, who created it as a nation within a nation, a Black refuge in the bloody storm where she learns to read and heal.

The price of freedom is raised in each section. Everywhere Cora goes, abolitionists, moderates and slave catchers all take turns exacting something from her. Sometimes it is her obedience or playing a role in their mythology. Other times it is her invisibility. Cora pays, but it is never enough. The tension in the novel spikes with each failure, sending her back into Ridgeway’s chains.

In this world escape is never enough. Hiding is never enough. The climatic struggle at the novel’s end points toward one clear message: The only way to be free is to destroy whatever is trying to take your freedom.

The Underground Railroad’s thematic image achieves its full power when we see Cora walking through its tunnels, without a map or plan. She runs her “hand along the wall of the tunnel, the ridges and pockets … fingers danced over valleys, rivers, the peaks of mountains, the counters of a new nation hidden beneath the old.” Colson ends with Cora stepping into her future: “She could not see it but she felt it and moved through its heart.”

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $34,000 in the next 5 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.