Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Washington – Under the political gun, the Pentagon has bulked up its anti-rape campaign far more than many people realize. It's expensive, aggressive and imperfect.

Training on preventing and dealing with sexual assault has proliferated. Sometimes it's tainted juries. Budgets have ballooned. So have bureaucracies. Lawmakers have tried to protect victims. Sometimes they've bungled the job. Higher-ups have demanded tougher action. Sometimes they've unduly cowed subordinates.

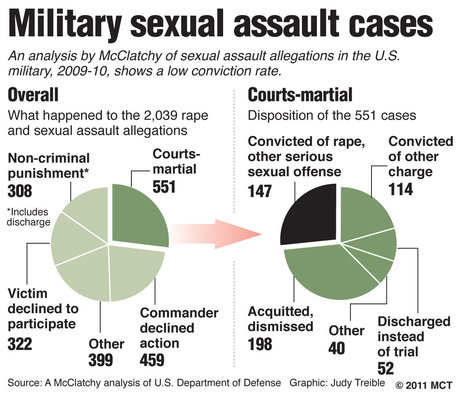

Contrary to public and political impression, an extensive McClatchy review of military sexual assault finds plenty of Pentagon and congressional action. Some works. Some falls short. Some goes too far, in a legal arena that's notorious for its complications.

“These cases are among the most difficult to handle because of the many thorny issues involved, like 'he said, she said' testimony, alcohol use and misuse of military position, and because they impact the ability of soldiers to live and work together,” noted Lisa Schenck, an associate dean at George Washington University Law School who's a retired Army colonel and a former senior judge on the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals.

Bureaucratically, the Pentagon undeniably has beefed up.

The budget for the Defense Department's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office leapt from $5 million in fiscal 2005 to more than $23 million in fiscal 2010. Once administered by a civilian with a doctorate in counseling, the office is now overseen by an Air Force major general with a background in security.

Total Defense Department spending on sexual assault prevention and related efforts now exceeds $113 million annually.

“The department has placed particular emphasis over the past few years on reducing the stigma associated with reporting incidents, ensuring commanders receive sufficient training and providing appropriate training and resources to investigators and trial counsel,” Defense Department spokeswoman Cynthia Smith said.

Some training aims to prevent misbehavior in the first place, with classes that have titles such as “Sex Signals” and “Can I Kiss You?”

The training gets mixed reviews.

Numerous service members confided that sexual assault and harassment training “is not taken seriously,” the Government Accountability Office noted in 2008. A 2009 Pentagon sexual assault task force likewise warned that some training, heavy on the PowerPoint, was only “marginally effective.”

And some of it can taint the military justice system.

One drink, service members periodically have been taught, renders a woman incapable of consenting to sex. This lesson is easy to remember and it draws a bright line: better safe than sorry. It's also legally inaccurate and can be dangerous in a courtroom.

Last year, for instance, Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Jamie Walton faced charges relating to a brief affair with a 19-year-old female Marine. The charges against the married Walton included sexual assault and providing alcohol to a minor.

Prospective jurors reported that they'd been taught that a woman can't consent to sex after only a single drink. The judge instructed them to ignore the training. One juror, a Marine staff sergeant, nonetheless said he couldn't reconcile his prior training with the new instructions.

“It's just integrity, sir,” the staff sergeant told the judge, a trial transcript shows. “I can't agree with it.”

The judge dismissed the staff sergeant, and Walton subsequently was convicted of adultery, which is illegal in the military. Although the judge managed to eject the juror who admitted a conflict, the question lingers whether jurors in other trials may retain their erroneous lessons.

Earlier this year, an Air Force enlisted man at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey was accused of sexually assaulting an intoxicated woman. Military jurors revealed that they, too, had been taught that any amount of alcohol rendered a woman substantially incapacitated and hence incapable of consenting.

“First of all, that's not the law,” said the enlisted man's attorney, Michael Waddington, “and it's not medically accurate.”

The erroneous lessons that stuck in the minds of jurors made his job more difficult, Waddington said, though his client eventually was acquitted of the sex-related charges.

With paperwork, too, the Pentagon is reinforcing its campaign against sexual assault. The Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office's first annual report, presented in May 2005, covered 10 pages.

By March 2011, the annual report and appendices spanned some 620 pages. It included significant statistical detail and a useful listing of each allegation. It also included ornamentation, such as a photograph of country singer Toby Keith posing with soldiers.

Raw performance sometimes has lagged. Congress directed the Pentagon in October 2008 to complete a comprehensive sexual assault database by January 2010. The Pentagon missed the deadline. Now officials hope to complete the database by August 2012, at an estimated cost of $12 million.

To motivate the military, officials employ sharp rhetoric and direct commands. In April 2004, notably, Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld ordered top commanders to “identify, remove and encourage the prosecuting of those responsible” for sexual violence.

Military officers began facing new obligations; their promotions could turn, in part, on how well they handled sexual assault issues. Prosecutions have proliferated. No commander, numerous military officers confided on the condition of anonymity, wants to be second-guessed for failing to prosecute even an iffy case.

This new command focus contrasted with what many veterans said was a prior blind eye, or worse.

Ohio resident Kori Cioca, for instance, was a Coast Guard enlisted woman when, she says, one of her superiors grabbed her by the hair in December 2005, pulled her into a stateroom and raped her.

She reported the attack, but she was the one who got in trouble.

“The command did not keep the rape and assault confidential,” Cioca's attorney Susan Burke reported, in a lawsuit filed on Cioca's behalf, “but instead permitted other military personnel to harass (her), call her names and spit on her.”

But as officials rivet attention and incite action to avoid a repeat of Cioca's experience, their rhetoric can charge ahead of the facts.

In late September, for instance, a California congresswoman took to the floor of the House of Representatives with a frightful tale of military sexual violence.

“Nineteen thousand rapes a year occur in the military,” Democratic Rep. Jackie Speier declared on Sept. 22, citing what she called Pentagon estimates.

Speier's horrific account was the latest in a weekly series she's delivered all year, spotlighting what she calls the “epidemic of rape and sexual assault in the military.” Equally bad, she says, is military indifference.

“The Department of Defense still testifies that there are 19,000 rapes that occur in the military every year,” Speier said in a House speech on June 15, ” and we have done nothing about it.”

Speier was misspeaking; usually her written statements refer to 19,000 “rapes and sexual assaults,” rather than rape alone. Even this, though, can be exaggerated.

By all accounts, rapes are underreported. The intimately violent crime can shame any victim into silence.

Last year, the military received 3,158 reports of sexual assault. Rape accounted for about one-quarter of the total. If only one in five military rapes is reported, as the Pentagon estimates, the annual number would be about 3,900.

The 19,000 number Speier cited was an extrapolation based on a survey of 2 percent of the military. It referred, moreover, to any form of “unwanted sexual touching.” This covered everything from a slap on the bottom to fondling to rape.

Speier, introducing a bill in November to impose a new system for handling military sexual assaults, further declared that “for too long, the military's response to rape victims has been, 'Take an aspirin and go to bed.' ” The sound bite was vivid, but it referred to a comment allegedly made in 1985 to Navy enlisted woman Terri Odam.

Since Odam's long-ago experience, part of the military's increasingly aggressive response involves training specialized personnel. More than 10,000 trained “victims' advocates” now serve in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force. In addition, more than 500 sexual assault response coordinators serve military installations and units.

This proliferation of trained personnel can help change the military culture, like a swelling of antibodies, but transformation can take awhile.

A victims' advocate, for instance, was summoned in March 2007 at Camp Lejeune, N.C., when Marine Lance Cpl. Maria Lauterbach said Cpl. Cesar Laurean had raped her. An advocate then accompanied Lauterbach to meetings with Navy investigators and counselors and conversed with her daily.

Lauterbach's victims' advocates largely performed well, a Defense Department Office of Inspector General investigation concluded this month. The unit's sexual assault coordinator, though, fell short.

“As a result,” the Office of Inspector General reported, “the professionals who met to discuss sexual assault cases were unable to facilitate Lance Cpl. Lauterbach's proper care and services or assure her safety, well-being and recovery.”

Lauterbach disappeared in December 2007. Her remains were found a month later. Laurean eventually was convicted of murdering her.

The political and military response to sexual assault has included revising the relevant laws. Judicially, this hasn't always turned out well.

In 2006, for instance, Congress changed the sexual-assault provisions of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Part of the intent, as Rep. Loretta Sanchez, D-Calif., said once, was to emphasize “the acts of the perpetrator, rather than the reaction of the victim during an assault.”

But in trying to protect the victim, the congressional rewrite caused considerable courtroom confusion by shifting the burden of proof onto those defendants who claim that the sex was consensual. The reasons are technical, but the result, according to Marine Corps Lt. Col. Raymond Beal II, a military judge, is “horribly flawed.”

“If you had 100 monkeys with a typewriter, they'd probably come up with something like this,” Air Force Col. Don Christensen, another military judge, declared during a 2009 aggravated sexual assault case,

The Senate is considering a defense authorization bill that would change, once more, the military law provisions. The prospects for the bill are unknown.

© 2011 McClatchy-Tribune Information Services

Truthout has licensed this content. It may not be reproduced by any other source and is not covered by our Creative Commons license.

Holding Trump accountable for his illegal war on Iran

The devastating American and Israeli attacks have killed hundreds of Iranians, and the death toll continues to rise.

As independent media, what we do next matters a lot. It’s up to us to report the truth, demand accountability, and reckon with the consequences of U.S. militarism at this cataclysmic historical moment.

Trump may be an authoritarian, but he is not entirely invulnerable, nor are the elected officials who have given him pass after pass. We cannot let him believe for a second longer that he can get away with something this wildly illegal or recklessly dangerous without accountability.

We ask for your support as we carry out our media resistance to unchecked militarism. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation to Truthout.