Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

A new survey shows arsenic levels in public water are disproportionately high in certain U.S. communities, despite national regulatory standards designed to protect people from the harmful chemical.

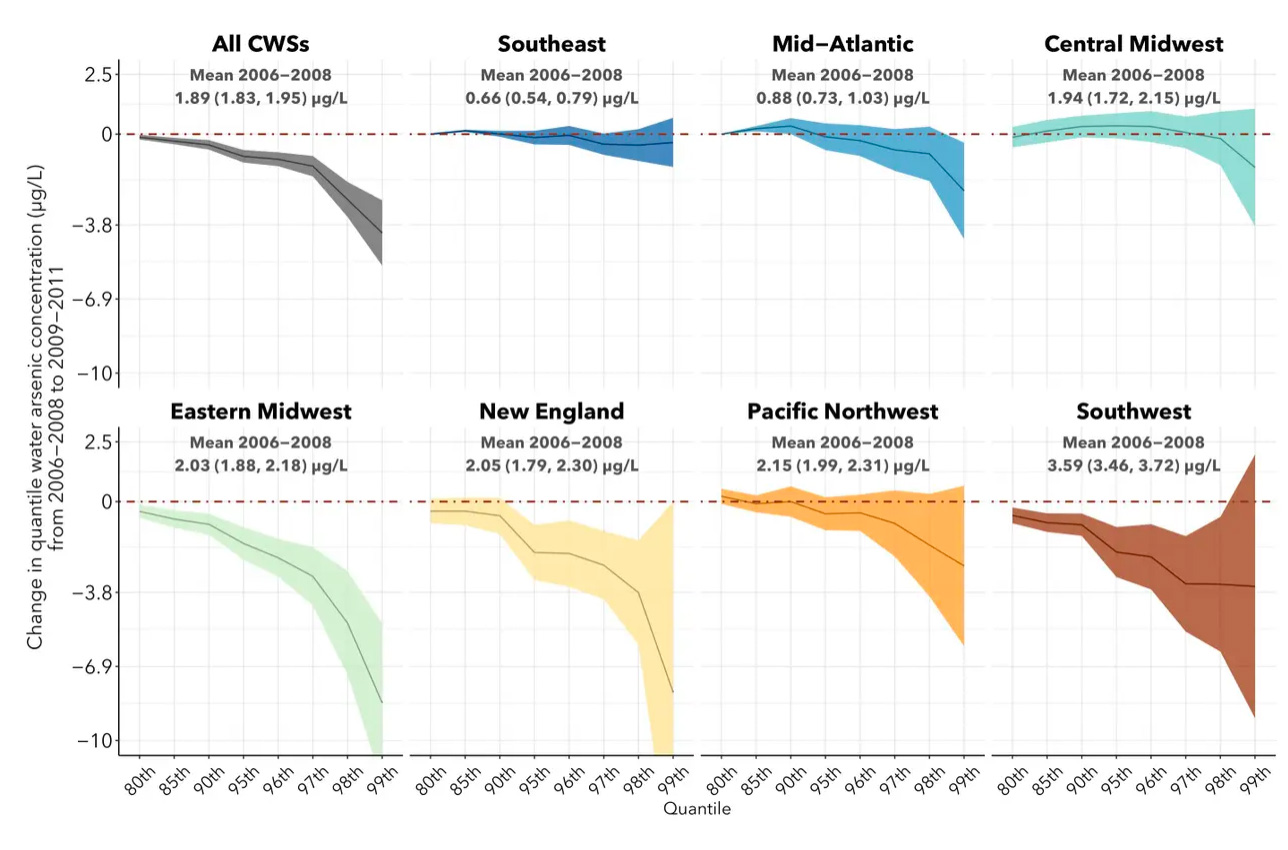

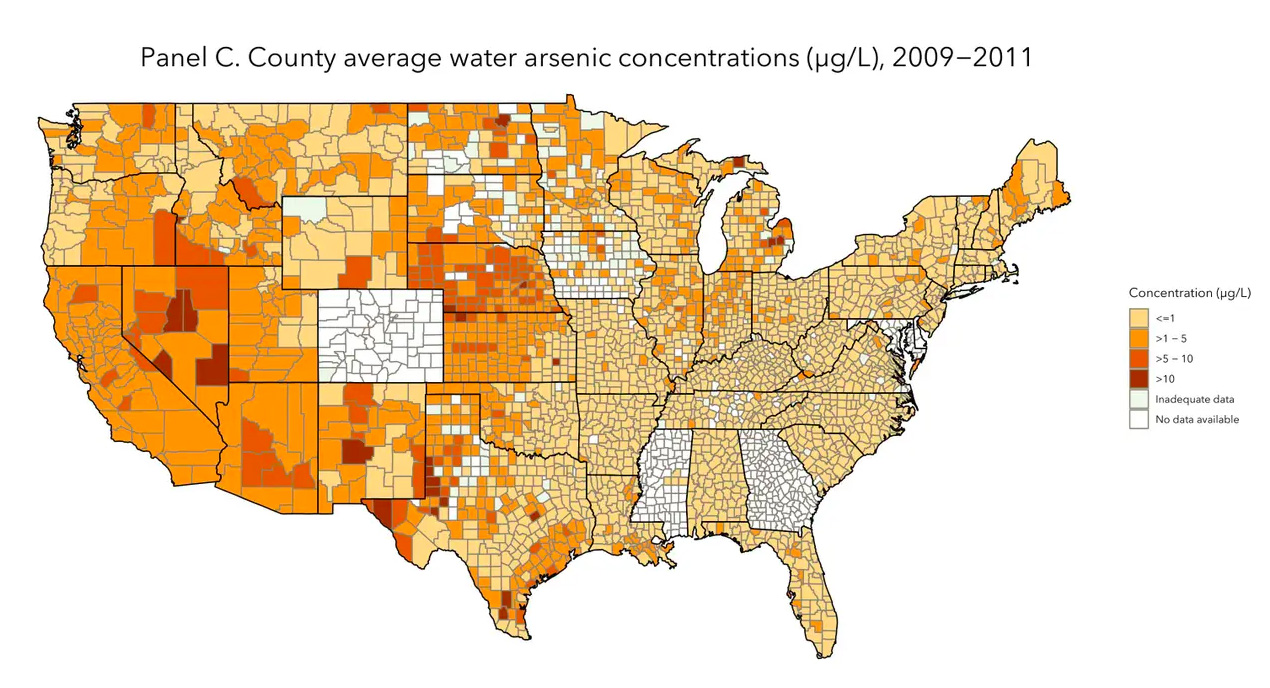

Researchers studied approximately 13 million records from 2006 to 2011 covering 139,000 public water systems in 46 states, Washington D.C., and Native American tribes. The records cover water service for 290 million people, representing 95 percent of all public water systems and 92 percent of the total population served by public water systems. Researchers found that, while average public water arsenic concentrations decreased by an average of 10 percent nationwide over the time studied, that decrease was not equal across all areas or demographic groups. Arsenic levels remained higher in water systems serving Hispanic communities and areas of the Southwestern U.S. Their findings were published this month in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Arsenic is a highly toxic carcinogen, and is “the most significant chemical contaminant in drinking water, globally,” according to the World Health Organization. Chronic exposure to arsenic has been shown to damage almost every system in the human body, resulting in conditions like heart disease, diarrhea, cognitive impairment, cirrhosis and lung disease, among others.

“We actually know very little about inequalities in public drinking water quality across the U.S.,” Anne Nigra, environmental health scientist at Columbia University and the lead author of the paper, told EHN. She added that these contamination levels across different communities are really important data points to collect — with these measurements you can see where inequalities lie, and further study how that exposure is related to disease.

Primarily Hispanic communities, smaller populations of about 1,000, and areas in the Southwest were more likely to have arsenic concentrations in drinking water that exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) maximum contaminant level, raising environmental justice concerns. The maximum contaminant level is the highest concentration of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water. The EPA determines these levels by considering the public’s health, but also the costs and feasibility of achieving and enforcing that standard.

Nigra and her team studied records from 2006 to 2011 because that was when the EPA began following up and enforcing their new, lowered thresholds for arsenic in water. The EPA announced in 2001 that the maximum contaminant level would go from 50 parts per billion to 10 parts per billion, to be enforced by 2006.

Ten parts per billion may be significantly lower than 50 parts per billion, but Nigra said that’s not enough. “The Netherlands has established a regulatory limit of 1 part per billion in drinking water. Denmark, New Hampshire, and the state of New Jersey, have all established a regulatory standard of five parts per billion,” she said.

Many counties exceed even that. The study results showed that there are still close to 500 counties whose arsenic levels crossed that threshold. It’s a great health concern, said Nigra, because “there is no safe level of arsenic in drinking water.”

The EPA’s maximum contaminant level goal is zero parts per billion.

Arsenic may not accumulate in the body the way other elements, like lead or mercury do, said Nigra, but if you are being exposed to arsenic through drinking water, that exposure is chronic, and “chronic exposure, even at low to moderate levels of exposure, is a real problem, and it’s a real threat to health.”

Speaking against the authoritarian crackdown

In the midst of a nationwide attack on civil liberties, Truthout urgently needs your help.

Journalism is a critical tool in the fight against Trump and his extremist agenda. The right wing knows this — that’s why they’ve taken over many legacy media publications.

But we won’t let truth be replaced by propaganda. As the Trump administration works to silence dissent, please support nonprofit independent journalism. Truthout is almost entirely funded by individual giving, so a one-time or monthly donation goes a long way. Click below to sustain our work.