Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

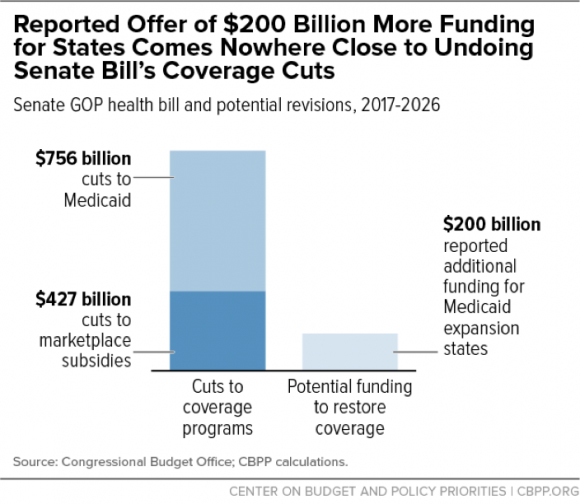

In a last-ditch effort to save their bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Senate leaders are reportedly offering $200 billion to win the votes of senators from states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA. This new fund would presumably supplement private coverage for those who gained Medicaid coverage under the expansion but would lose it under the Senate bill. No senator should fall for it. While $200 billion seems like a lot of money, it’s only 17 percent of the bill’s $1.2 trillion in cuts: $756 billion from Medicaid and $427 billion from subsidies to help low- and moderate-income people buy coverage in the individual market, according to the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates (see first chart). It wouldn’t even fill the federal funding gap left by repealing the Medicaid expansion — let alone prevent the harm from the bill’s per capita cap on federal funding for all of Medicaid and the loss of subsidies and erosion of market reforms for people with individual market coverage.

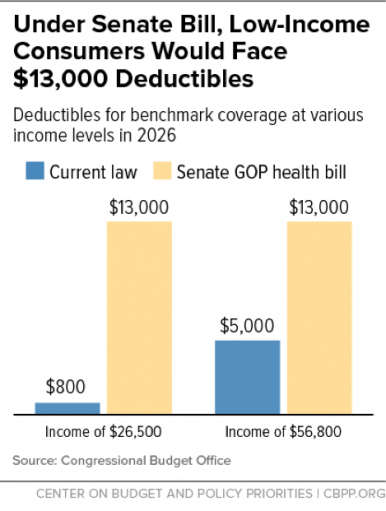

Effectively ending the expansion accounts for about three-quarters of the $756 billion cut in Medicaid, according to CBO. Providing affordable private coverage to poor and near-poor individuals would likely cost more than covering them through Medicaid — that is, far more than the $200 billion that Senate leaders are proposing. That’s because Medicaid coverage costs 22 percent less for comparable beneficiaries, even though Medicaid provides more comprehensive benefits and far greater financial protection. Today’s CBO score shows how big a hole supplemental coverage would have to fill under the Senate bill. The private plans available to people would have deductibles of $13,000 by 2026 (see second chart).

Moreover, news accounts suggest that the additional funding — like the bill’s other state grants — would completely expire in 2026, even as its Medicaid cuts would grow in the second decade.

This new fund would do nothing to fix the major problems that the bill would create:

• It would do nothing to offset the Medicaid cuts resulting from the per capita cap, which would affect children, seniors, and people with disabilities in all states. These cuts would shift ever-increasing costs to states, forcing the states to respond by making ever-deepening cuts in eligibility, benefits, and provider payments.

• It would do nothing to address the bill’s harm to people with private coverage, including the loss of coverage for millions of people (due largely to sharp cuts in marketplace subsidies), increased costs for those who stay covered, and the loss of access to health care for millions with pre-existing conditions.

• It would do nothing to address the fact that millions of lower-income marketplace consumers in non-expansion states would see their deductibles jump many thousands of dollars under the Senate bill. Because of these increases, “few low-income people would purchase any plan” and most would become uninsured, according to CBO. The bill would also effectively prevent non-expansion states from ever expanding Medicaid to provide affordable coverage for people in poverty, as a number of non-expansion states (including Maine, Kansas, North Carolina, and Virginia) have recently considered doing.

The fact that Republican leaders are adding another fund — on top of their $45 billion to address the opioid epidemic, unrealistic promises of federal waivers to use Medicaid funds to help cover people losing Medicaid coverage under the bill, and inadequate, poorly designed stabilization funds — is more evidence that the Senate bill can’t be fixed. Throwing more money into a patchwork of poorly targeted funds that perpetuate the inequities in coverage between expansion and non-expansion states is no substitute for the Medicaid expansion, which has been highly successful in increasing coverage and access to care, including treatment for opioid addiction.

There’s no justification for building such a Rube Goldberg device. As hospitals, doctors, nurses, patients, and governors of both parties have said, Medicaid expansion is working well now and should remain in place. Policymakers should also reject a per capita cap that shifts costs to states and beneficiaries. No one should be fooled: The reported $200 billion can’t fix the basic problems with this bill.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.