Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

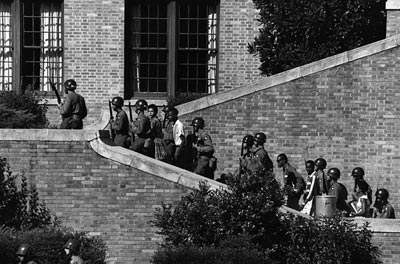

Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little Rock Nine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., 1957. (Photo: National Archives)From police killings, to Stand Your Ground laws, to Medicaid refusal in majority-minority states, 50 years after Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Act, activist Mab Segrest says structural racism is not just a problem for Missouri.

Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little Rock Nine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., 1957. (Photo: National Archives)From police killings, to Stand Your Ground laws, to Medicaid refusal in majority-minority states, 50 years after Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Act, activist Mab Segrest says structural racism is not just a problem for Missouri.

On August 9, 2014, Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old. The scenes that have played out since, of heavily militarized police shooting at protesters in a suburb of St. Louis, have left many wondering what happened to the gains of the civil rights movement.

Mab Segrest, a writer, activist and professor, grew up in Alabama in the 1960s. Her influential autobiography, Memoir of a Race Traitor, has inspired generations. Growing up in a segregationist family, Segrest has studied, organized and taught against white supremacy, patriarchy and homophobia her entire life.

While this conversation preceded the killing in Missouri, it couldn’t be more relevant. In it, Segrest describes, as a young child, watching the adults around her deploy brute force against integration at her high school. It was a “confusing” moment, she recalls, but also a “moment of emancipation in terms of consciousness . . .”

In 1966, a distant cousin of Segrest’s admitted killing Sammy Young, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, yet he was acquitted by an all-white jury. “It was the end of tactical nonviolence,” says Segrest in this interview.

Structural racism is not just a problem for Missouri (as many have pointed out, it was the last of the slave states). From police killings, to Stand Your Ground laws, to Medicaid refusal in majority-minority states, 50 years after Freedom Summer and the Civil Rights Act, says Segrest, we “haven’t broken the paradigm” of white supremacy in America. Far from it. “The ideology is very recognizable,” she says.

Our race history lives in us. “It’s subjective, but it’s never just personal. It’s embedded in our families,” says Segrest.

Still, there is inspiring new organizing taking place. In particular, Segrest holds up Project South and SONG, Southerners on New Ground, of which she was a co-founder.

While the youth of Ferguson and the world watch another brutal display of force policing race lines, what will this generation’s struggle spark? Another SNCC? More white “race traitors”? Break that paradigm at last?

You can watch the full conversation with Segrest at GRITtv.org. GRITtv can also be seen on the new, news channel, TeleSUR English – for a different perspective.

Laura Flanders: Let’s start at the very beginning. You grew up in Alabama at the height of the civil rights movement. What did you see?

Mab Segrest: Well, it wasn’t just Alabama, it was Tuskegee, Alabama and Macon County, so there is particular local culture in terms of race and civil rights. Tuskegee was the home of Tuskegee Institute and it had the largest – when I was growing up – proportion of black people living in a county in the United States: 85 to 89 percent . . . A white minority across the south [of] 10 to 15 percent controlled the 85 percent.

Do you remember how you made sense of that as a kid?

It didn’t occur to me much until it started occurring to everybody; until the civil rights movement literally came to town and not only came to town, but came to our front yard. I think I had been fairly complacent; I knew certain kinds of things and I had conversations with my mother, but in 1963 the first four public schools desegregated in Alabama. It was my high school. I was in the ninth grade. I got ready to go to school knowing that we were going to be integrated and my dad came and said you’re not going to school because George Wallace has sent a hundred state troopers – some of them on horses – to close down the school.

George Wallace the governor of Alabama whose famous phrase was “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” So, troopers to your front yard . . .

The media were in our front yard; we were two doors down from the school. The troopers were surrounding the school so we were all surrounding the troopers and I was under the bushes looking out at everything. It was quite incredible and all of a sudden everything stopped.

Everybody in the town had been gearing up since August to make integration work. Surprisingly given all of the resistance that happened later. The board of education had put things into place. The student council (I had gone to student council meetings) we had plans to kind of segregate the social activities, but we’re going to just try and make it work. When that happened though, Wallace really put a wrench into the works, and the next week there was a whole set of moves and counter moves by him and Fred Gray who was an African-American lawyer who had brought the [desegregation] suit in the first place, and they went in to get a federal restraining order and Wallace threatened to bring out the National Guard and then the federal judge Frank Johnson threatened to nationalize the National Guard so within a week, 13 black students came to the school, but white students by then had pretty much been discouraged.

You mentioned that your family wasn’t on the desegregation side of things. You have a personal connection to one of the killings of that era.

Right. The killing was two years later, but ’63 to ’66 is kind of a portal for Tuskegee and certainly for me in these 50-year commemorations. It turned out in that week of interregnum, Wallace stopped everything and four parents got together and decided to go to Wallace and start a segregated private school which was the first in Alabama because Tuskegee was the first public school to desegregate in Alabama. By the time school had opened, there was a movement of white parents to start what turned out to be Macon Academy, which I went to. I was quite surprised that my mother had done it.

Surprised that they sent you to the segregated school?

They started the school; they didn’t just send me to it; they started it. It was quite confusing but it was for me this moment of emancipation in terms of consciousness, to see how much force could be martialed to stand in between children and to realize that there’s something profoundly wrong with the white supremacist mindset that was behind all of this. I mean I had never seen it play out quite so vigorously. . . .

In 1966 Sammy Young was one of the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) leaders in town [who] was shot and killed at a gas station, having asked the white station attendant to go to the white bathroom. He was sent around the door to the back, and he protested and there was an altercation and he ran, and the station attendant had a rifle and shot him in the back of the head and killed him. His name was Marvin Segrest. He was a cousin of mine – distant cousin I never met him – but I do remember the phone call that night where my dad had gotten a call from the jail and said Marvin Segrest had shot Sammy Young, and I didn’t know who Martin Segrest or who Sammy Young was. There were demonstrations in the town. Segrest who said he’d done it – he was standing there with the rifle – was indicted later and was acquitted by an all-white jury in the next county which didn’t have any black people on the voting rolls.

It was the end of tactical nonviolence. SNCC came out three days later against the war in Vietnam, which was the first civil rights organization to do that, and there was an upsurge in black voter registration, especially from the county, and a shift towards black power which is what SNCC and Sammy Young and those folks had been much more involved in. In the liberal regime, the white sheriff had been good to appoint one black deputy, but soon after that they elected the first black sheriff in the South. That window in terms of these 50-year anniversaries and the one that’s coming up, framed my most intense memories of that time.

And your growth out of that?

It terrified me, actually. The more I thought about it, the more I saw my family and outside of it – the more I just felt like I had to get away. I didn’t realize until later when I went to Duke to graduate school in the ’70s, and then came out as a lesbian, that there was a sense of “I can’t live here.” When I came out, there was a very vibrant and political lesbian community in Durham and they were doing all kinds of activism so I started doing feminist and anti-racist activism very soon there and that allowed me to go back and pick up the experiences from my childhood and make more sense of it.

You made beautiful sense of those experiences in your book, Memoir of a Race Traitor, and I encourage anybody to pick up the book and read it through, but there are a couple of things that you address in the book that I would like to just pick out: One is white guilt. Looking at your story a lot of people might say, how did you get the chutzpah to go back and work in the black community, let alone work against white supremacy? What did you do with your own sense of personal and family responsibility, and is it personal, the guilt?

Do a structural analysis. What’s happened in the South? What was the history of slavery? What’s happening in the economy? Why are all of these white people in the ’80s being pulled into Klan movements? What’s the history of struggle; how do we relate to this? Who are the white people who have been in the struggle before? It’s subjective, but it’s never just personal. It’s embedded in our families in that way – all of this stuff around subjectivity.

I did a critique and a history, “On Being White and Other Lies.”

I looked at the genealogy that my mother had left to me – to be in the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Colonial Dames [of America], Daughters of the Revolution. I had white ancestors back to 1609 in Jamestown. I just followed them up and told the story of white settler colonialism and what happened to white people in those struggles.

By the time I was able to recognize it, some of the things that were impacting my own family from having fought in racist wars and been in racist structures and things like that. In some visceral way [I] recognized this profound damage to my parents and our family structure that went back generations that [I] felt increasingly had to do with race. How do white people understand race doesn’t just stop here, but we’re constituted by it, which was kind of the field of whiteness – all of this “whiteness studies” in the middle of the ’80s . . .

Now there has been some criticism of whiteness studies that it suggests to some that whites are somehow the victims, which is not what you’re saying, obviously.

No, whites are not neutral. It’s not reverse discrimination at all . . . The racist position is that whites are neutral and look out at all of those people of color who have various pathologies, who are working so hard, or have these cultures that are so exotic and colorful and we’re not in the picture. After generations, if not centuries, of black people saying white people need to tend to their own histories, [mine was an] effort to try and trace the history of the emergence of white identities in the context of white, settler colonialism; just to decentralize it in a way.

I think the other part of my book that folks have appreciated is the record of activism and this is not just “oh, well . . . because of this identity . . . I’m doing this kind of activism and I’m documenting it. [But rather] what does it feel like to be a white person, a lesbian with my family history who is doing lots of work across North Carolina for six years.

In terms of the 50-year anniversary and the issues that were up for debate and were being fought over at that point which, among other things, were economic self-determination, political representation, access to public goods and the mobility through the society – you can add to the list – what’s happened?

Well, we haven’t broken that paradigm yet, clearly. It’s a very Southern paradigm that I think has very national and I think global repercussions.

The paradigm of white supremacy or one group’s supremacy in power?

. . . And how it’s manipulated and held in place. Racist violence in 1966, Sammy Young is shot and killed. Trayvon Martin two years ago with Stand Your Ground laws in 26 states it says, “if you’re afraid of them, shoot them. If you need to defend yourself because you’re afraid, then shoot them.” And that’s defense in court.

Which is the argument that most of the Klan leaders made. I was under threat.

Right and what Marvin Segrest made after he shot Sammy Young and got off for that.

Or lack of access to public resources and public goods which has always been brutal in the slave and post-slave South and now with 23 states – somewhere in the twenties – they turned down Medicaid from the Affordable Care Act and 10 of them are in the Southern states, but almost 80 percent of the people who are being denied insurance from the Affordable Care Act are in the South. Those legislatures turning [care] away [have] higher concentrations of poor people, many of whom are people of color.

If it’s Stand Your Ground, if it’s the Medicaid refusal, if it’s the super-majorities [in state legislatures], if it’s Republican ideology, and organizing that’s such a contest in the rest of the country . . . there’s a Southern base to that.

The ideology is very recognizable from the history of the slave and the post-slave culture. You can look at it too from the Southwest and you can see the conquest of Mexico in 1848. You can see what happened to indigenous people. You can read all of those things. They are still there in our DNA. We have not broken it at all. So those kind of battles, they are very familiar battles. We have records of them and there are new strategies too.

Talk about some of those new strategies. Are we hearing the same language today that was used 50 years ago or has it gone in for an update?

There’s definitely an update. Two of the organizations in the South that friends are working on that I’m most excited about is Project South for the Elimination of Poverty and Genocide and Southerners on New Ground or SONG and Project South came out of the movement of the ’60s with SNCC folks at the helms of them, and have been doing very wonderful organizing for 50 years now.

With new leadership now, they helped to host the first US Social Forum in Atlanta after [Hurricane] Katrina, and really focused on Katrina and the diaspora there, and the organizing response to it, which really shook some organizers. People realized it at a whole different level when the state abandoned you at that level. What do you do? What’s self-sufficiency? What’s more interdependence in communities and how can you hold states accountable, and how can you win when you’re not able to?

And SONG?

Southerners on New Ground formed in probably 1992 or ’93. I was one of the six founders so, I’m very proud here. We’re lesbians, black and white, who had been working both within lesbian and gay movements and broader issues of equality, and within those broader movements on questions of sexuality and homophobia. Right now SONG is doing really brilliant organizing across the Southeast: very queer, very multi-issue, very network into a range of organizations. It’s not single-issue anymore; it’s not identity-based anymore, liberation in our lifetime, queer liberation in our lifetime, ignite the kinship. Both of those organizations I am very proud of and very inspired by.

If you had one message to people who are trying to take advantage of this 50th anniversary, to maybe bone up on history they never knew, to teach classes they never taught or read books they never read, or do things they hadn’t done before, what’s your message?

Be brave. What’s that song, [“Brave”] “I want to see you be brave”? I want to see me be brave. It’s such an amazing piece of history where so many people, together, decided to be so brave and that there was something worth more than their lives.

Thank you so much for coming in.

You’re welcome.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have a goal to add 273 new monthly donors in the next 72 hours. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.