Part of the Series

Truthout on the Mexican Border: Revealing What Is Behind the US War on Drugs

Support Truthout’s work by making a tax-deductible donation: click here to contribute.

This is the sixth article in Truthout’s series looking at US immigration and Mexican border policies through a social justice lens. Mark Karlin, editor of BuzzFlash at Truthout, visited the border region recently to file these reports.

Previous installments:

- The US War on Drug Cartels in Mexico Is a Deadly Failure

- The Border Wall: The Last Stand at Making the US a White Gated Community

- Murder Incorporated: Guns, the NRA and the Politics of Violence on the Mexican Border

- Latina Leaders of Texas Colonias Help Remake Shantytowns Into Empowered Communities

- A Poet’s Pain Launches a Peace Movement in Mexico

Reporting on Murder and Corruption in Mexico Can Be Deadly

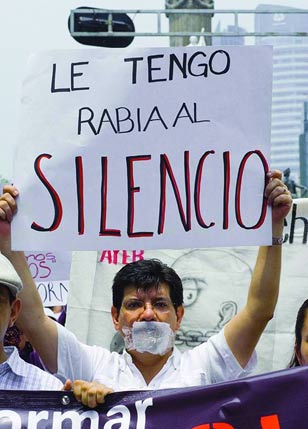

Journalists are being killed, wounded and threatened at an alarming rate in Mexico since the US/Mexican war on drugs accelerated into a bloodbath of deaths, wounding and torture beginning in 2006.

What is the impact of this brutal attempt to suppress the reporting of violence and crime in Mexico?

Take the newspaper El Mañana published in Nuevo Laredo. Unreported by US papers as far as Truthout could determine, El Mañana wrote an editorial on May 13th that it would no longer report on crime in the city (which sits just across the Rio Grande from Laredo, Texas):

This newspaper is calling for the understanding of the public as we will abstain from publishing, for the time being, any news about the crime and violent disputes that our city suffers as well as other areas of the country.

The editorial board and administration of this paper has arrived at this lamentable decision due to the circumstances known by all – and due to the lack of conditions for the free exercise of journalism. [translated by Truthout]

The editorial was posted two days after the office of El Mañana was shot up by a fusillade of bullets during the night shift, although no one was wounded.

Not the First Attack on Journalists in Nuevo Laredo

It was not the first time that the Nuevo Laredo periodical was attacked. According to a Laredo, Texas, television station, El Mañana was shot up and reporters wounded in 2006. Roberto Mora García , the editor of the paper, was assassinated in 2004.

There have been other attacks in Nuevo Laredo on journalists, including the killing of Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro. Her murder by decapitation was, according to the international Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), “the first ever documented by CPJ worldwide that was in direct relation to journalism published on social media.”

Prior to El Mañana’s reluctant announcement that it would no longer report on crime, Nuevo Laredo experienced a macabre display of the barbarous toll of the war on drugs. As The Washington Post reported:

In a bold public display of the gang violence sweeping across northern Mexico, residents in the border city of Nuevo Laredo awoke at dawn Friday to find nine corpses of men and women hanging from a bridge at a busy intersection just a 10-minute drive from Texas.

A few hours later, authorities discovered 14 headless bodies wrapped in plastic bags, stuffed into a sport-utility vehicle in front of a Mexican customs agency. The 14 heads were later placed in plastic-foam coolers and left by armed men on a crosswalk beside the city hall, according to the attorney general in Tamaulipas state.

The True Number of Killed, Wounded and Tortured Journalists in Mexico Is Not Known

Mexico is undergoing an ongoing assault on journalists, including the killing in the last few years of at least 45 reporters and photographers, as estimated by CPJ’s Mike O’Connor. However, O’Connor, who reports from Mexico, explained to Truthout that the figure might be on the low side because the CPJ has rigorous standards for identifying who constitutes a working journalist. Furthermore, due to the lack of police investigations in the vast majority of murder cases, it is not clear how many journalists are killed for what they have revealed in print or just for knowing too much information. O’Connor must investigate much of the scant details available about the killings himself. Even then, doubt often lingers as to why a reporter or photographer died.

In addition, logically, the number of wounded journalists probably exceeds the figure for reporters and photographers who have been killed, but no statistics are kept of media survivors of attacks in Mexico. Nor is it clear how many newspapers or reporters have been shot at or intimidated without sustaining injury, as in the recent case of El Mañana.

As the CPJ reported in its 2012 “Impunity Index: Getting Away With Murder,”

Impunity is the oxygen for attacks against the press and the engine of those who seek to silence the media,” said Javier Garza, deputy editor of the Mexican daily El Siglo de Torreón. Gunmen have attacked his newspaper’s Coahuila offices twice in the past four years and, though fatalities were avoided, no one has been arrested either. “These attacks made it clear to us that we can’t trust the authorities for protection.”

What this leaves, as papers and reporters self-censor their reporting on violence to protect their lives (and those of their families), is a community uninformed as to the extent of crime in their cities. Killing and intimidating reporters suppresses the horror of the war on drugs and helps dampen a call for punishment for acts of violence.

Juarez Journalist: “Most of the Time We Don’t Even Know Where the Threat Is Coming From”

In Juarez, far to the west of Nuevo Laredo on the Mexican side of the border with Texas, Sandra Rodríguez Nieto courageously continues to report on corruption and a dystopian culture of murder for the newspaper El Diario. In 2011, she was honored with the Knight International Journalism Award (also given to her reporting partner Rocío Idalia Gallegos Rodríguez). In her acceptance speech, Rodrguez laid out the dilemma faced by Mexican journalists: “Most of the time we don’t even know where the threat is coming from. Sometimes it’s from the drug traffickers, other times it’s from the police officers, soldiers or politicians with links to organized crime.”

Two of Rodríguez’s colleagues were slain in recent years, which have seen murders in Juarez reach over 3,000 killings in 2010 (although they have been decreasing somewhat since then). But as many corporate mainstream US reporters in DC comfortably play the role of echoing government message points and engaging in high-paid punditry, Rodríguez risks her life on a daily basis.

“Journalists are killed with impunity in our country. We are all unprotected in a city where killers have no fear of being punished,” said Rodríguez in her Knight award acceptance speech. “It also has been hard to protect our hearts. The collective pain is sometimes unbearable in our city. But we keep reporting because this is the most important story of our lives.”

Even among the few murders that are solved in some areas, it is not at all clear that the police have identified the actual murderer. In the case of the killing of one of the El Diario journalists whom Rodríguez worked with, the paper investigated the accused killer and found that the police had tortured an unlikely suspect into “confessing” to the crime.

Whether the Slain Journalist Is a Man or Woman, Don’t Expect Justice

The Houston Chronicle reported on the recent slaying of Regina Martínez Pérez, who was found beaten and strangled in her home in Veracruz, a city on the Gulf of Mexico. Martínez covered the crime and corruption beat for the newspaper El Proceso. The Chronicle reinforced the theory that corruption, a weak legal system and the use of monstrous fear virtually ensures that “hits” go unpunished: “murders are rarely solved in Mexico.” The Chronicle restated the common suspicion, “and when they are, there are many doubts that authorities have even charged the right person.”

Shortly aver Martinez’s brutal killing, more journalists were killed in Veracruz.

As reported by the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, “Five of the eight journalists killed in Veracruz in the last 10 months worked for the local newspaper Notiver, which stopped publishing reporters’ bylines on stories related to crime and security issues, reported the newspaper Diario de Juárez.” The assault on the fourth estate in Mexico has become so brazen and deadly that reporters were reportedly told by newspapers not to attend the funerals of their colleagues in Veracruz.

Furthermore, the Knight Center revealed a detail about Martínez’s reporting that may shed some insight as to why some journalist murders quite likely come from governmental entities, including the military. “In 2007, the local newspaper Politica fired the journalist [Martinez] for reporting about an indigenous woman who was raped and killed by military men,” the Knight Center recounted. “Martínez disproved the official version that stated that the woman had died of natural causes, according to the newspaper Diario.”

So, not only did Martínez expose that the military was likely responsible for a rape and murder, she may have been killed for revealing or hinting at such truths on a regular basis.

Much doubt exists about claims that the drug cartels are behind all the murders. According to NPR, Mexican Congressman Manuel Clothier, strongly believes that “the majority of the aggressions against journalists come from those in power, not from organized crime.”

A Failed Mexican Federal Program to Protect Journalists and a New Constitutional Amendment

O’Connor of CPJ writes of a failed federal program, called the “protection mechanism” in English, that was supposed to provide FBI-style security to targeted journalists. It ended up being an understaffed, powerless entity. Instead of being a refuge, the program may have been a trap, since no journalist can truly trust any level of government with information that might lead to their murder. In short, the journalist protection initiative of President Felipe Calderón has been more of a public relations stunt than a means of ensuring that reporters can disseminate the truth without fear for their lives.

Recently, the Mexican Senate passed a constitutional amendment that “would modify Article 73 of the Mexican Constitution to say that federal authorities would have jurisdiction over any crime against, ‘journalists, people, or outlets that affects, limits, or impinges upon the right to information and freedom of expression and the press.'” O’Connor and the CPJ lobbied for the amendment, which now has to be ratified by a simple majority of states in Mexico.

O’Connor remains cautiously optimistic about future federal prosecution of crimes against journalists mandated in the amendment, but he acknowledged that the new amendment could also fail to be effective, even if approved by the states, if not funded sufficiently or if federal authorities are not given enough independent prosecutorial power. Mexico does not have an aggressive history of the federal government intervening in state and local murder prosecutions (which are as low as 1 percent in some states and cities), nor has it even shown much interest in doing so – let alone does it have a legal mandate to do so, in most cases. There remains the additional question (noted earlier) as to what extent some high government officials (including the military and police), for reasons of corruption, don’t want murders resolved because they are protecting the killers or may themselves be involved with groups that carried out the assassination.

When Social Order Disintegrates Into a Crime Factory

Sandra Rodríguez, (who was also honored as a hero of the media by The Los Angeles Times in 2010) recently published a book whose title in English translates to “The Crime Factory.” It is about how political, law enforcement, military and drug corruption – along with the exploitative maquiladoras (low-wage assembly plants that proliferated after NAFTA) have created an environment that nurtures brutality and murder among young people.

Rodriguez discussed her book with an interviewer for El País International:

Cuando uno habla de cártel se refiere al traficante, al sicario, al policía y a las autoridades. Si los grupos del narco son tan poderosos es porque han contado desde el principio con la protección del gobierno.”

When one speaks of the cartels, one is referring to the trafficker, the assassin, to the police and the authorities. If the narco groups are so powerful, it is because they have counted on the protection of the government from the beginning.” [translated by Truthout]

If most journalists in Mexico and publishers are not as brave as Sandra Rodríguez, who can blame them?

But without the likes of Rodríguez and her partner Gallegos, “the public does not know what is going on,” according to CPJ’s O’Connor. “The basis of democracy is an informed public.”

Reporters being chosen as targets of murder and shootings by people who want to stay in the dark is clear; who is ordering and doing the killing of journalists in Mexico is not. In some cases, they most likely include partners of the United States in the ill-fated war on drugs.

“This is what we are supposed to be doing,” Rodríguez said of her profession in a video that profiled her and Gallegos. “I live here. I am a reporter. I love this place. This is the job. These are the circumstances, and I am going to pray not to die, not to get killed.”

The next installment of Truthout on the Border will be on Sunday, June 2.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.