Part of the Series

Truthout on the Mexican Border: Revealing What Is Behind the US War on Drugs

Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

Do you support Truthout’s reporting and analysis? Click here to help fund it.

This is the fourth article in Truthout’s series looking at US immigration and Mexican border policies through a social justice lens, focusing on the lower Rio Grande Valley, Brownsville, Texas area. Mark Karlin, editor of BuzzFlash at Truthout, visited the region recently to file these reports.

Previous installments

The US War on Drug Cartels in Mexico Is a Deadly Failure

The Border Wall: The Last Stand at Making the US a White Gated Community

Murder Incorporated: Guns, the NRA and the Politics of Violence on the Mexican Border

When Roads Turned to Mud in the Colonias

Just outside of Brownsville city limits in Cameron Park, Texas, Lupita Sanchez used to park her car a few blocks from her home whenever it rained. The streets of the colonia where she lived were unpaved until 1996. If Sanchez dared to drive all the way to her house, she risked getting stuck in the mud, or, worse still, ending up in a sinkhole and waiting for the road to dry, when her car could finally be towed.

Now Sanchez is coordinator for community action services at Proyecto Juan Diego in Cameron Park, and she works tirelessly to improve conditions in what is becoming an empowered community of about 8,000 people.

Colonias in the United States are unincorporated, low-income communities outside of incorporated cities stretching from Texas to California, but the majority of colonias are in the Lone Star State. The Texas secretary of state estimates the state’s colonias number around 2,300, with the highest number, approximately 1,500 colonias with as many as 300,000 inhabitants, in Cameron and Hidalgo counties at the state’s southernmost tip. These figures are not exact: there is not one agreed-upon definition for colonias, and some colonia residents are undocumented (although at least one estimate is that at least 80% of colonias residents are US citizens, but these are still speculative numbers).

In “Shrub,” Molly Ivins’ and Lou Dubose’s book about George W. Bush, Ivins described the colonias just north of the Mexican border: If they “were a separate nation, they’d look like a Central American republic.” Some colonias still have sand or clay streets, and many individual homes still lack basic necessities, such as sewer and water service, that most people take for granted in the United States.

Through civic engagement, most colonias no longer have mud roads. (Photo is courtesy of Proyecto Azteca.)Colonias Created by Land Speculators Taking Advantage of Weak County Governments

Through civic engagement, most colonias no longer have mud roads. (Photo is courtesy of Proyecto Azteca.)Colonias Created by Land Speculators Taking Advantage of Weak County Governments

US colonias are poor, Mexican-American and long-neglected by all levels of government, although that is changing somewhat – but not without a fight. Colonias grew because land speculators created the subdivisions in unincorporated county areas. In Texas, counties are relatively weak as governmental entities. As a result, land was deeded out to poor Mexican-Americans and migrants. The plots were repossessed if payments weren’t made. This allowed a profiteering developer to turn a small parcel of land over several times without any of the inhabitants accruing equity, and the landowner was not required to go through the foreclosure process.

This changed somewhat in 1995, when the Texas legislature passed legislation requiring land speculators to register deeds with the county, but there are still ways to repossess the land, in the absence of prompt payments, with legal maneuvering and weak county enforcement.

What’s more, until 1994, colonias were most often built without basic electrical, sewage and water services, and many roads were left unpaved. Now, these services are legally mandatory, but the mandates are not always enforced. Furthermore, the state does not allow counties to enact building codes to prevent substandard housing. While the situation for many of the colonia inhabitants has improved, it still remains an uphill struggle to obtain basic residential services and secure, sustainable housing.

Colonias Organize for Positive Change

It would be easy for this to become a story about the woeful conditions of life in the colonias and how the poor were once again pick-pocketed by the wealthy. And that would be true. But I found that while the colonias that I visited late last year face a host of serious challenges, there is an active network of committed social-service and advocacy organizations that are creating meaningful change by helping colonia residents claim their own power. I also began to consider how reinforcing the notion of powerlessness is just another form of keeping power from people who are subjugated.

To Lupita Sanchez, change comes one streetlight at a time. Proyecto Juan Diego coordinated a campaign to end Cameron Park’s dark nights. It took commanding respect from political officials through increased voter turnout, cooperation with the utility company, the community’s willingness to pay an extra property tax charge, and ongoing pressure. Now, Sanchez points with pride at the arcing lights that line the paved streets, which used to be dirt roads.

Sanchez and her staff also rallied residents to contract for garbage and recycling collection. Because there were no areas for exercise in Cameron Park, Proyecto Juan Diego helped pull together resources to build a park with a community center and walking path.

Achieving basic services is a big accomplishment in the colonias, but these services create something even more powerful in their wake: a sense of community and a sense of ownership of one’s life and one’s future.

Creating an Equal Voice for Poor and Working Families

Former priest Michael Seifert ministered and agitated in Cameron Park for many years before he left the priesthood and became a colonias network coordinator for the national Marguerite Casey Foundation Equal Voice initiative for poor and working families. In a report on the Equal Voice project, the Marguerite Casey Foundation states that, “the 37 million people – 7.7 million families – who live in poverty are experts on family issues, yet their input has rarely been sought.” According to the foundation, one of the major goals for coordinators such as Seifert is to, “elevate the voices of the families into the public debate,” motivating those who feel powerless to realize that they have the ability to make positive change.

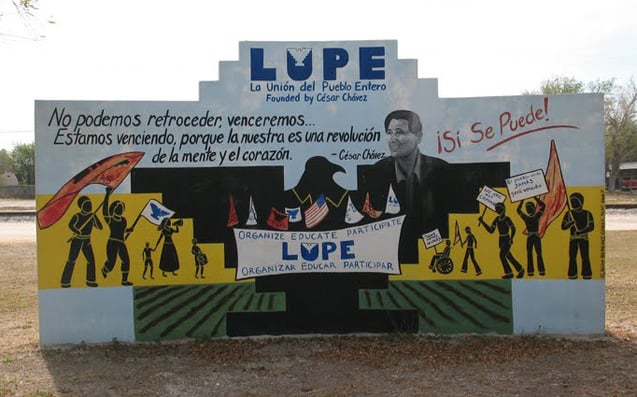

Former priest Michael Seifert now is the coordinator for the Equal Voice Rio Grande Valley colonias initiative. (Photo by Mark Karlin.) Equal Voice organizations meet regularly and have formed task forces for the colonias working on health, jobs and economic security, education, housing, immigration and civic engagement. One example of the effectiveness of a strategic approach to empowerment in the colonias was a recent cumbre, or community summit meeting, convened by Equal Voice member La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), headed by United Farm Workers veteran Juanita Valdez-Cox.

Former priest Michael Seifert now is the coordinator for the Equal Voice Rio Grande Valley colonias initiative. (Photo by Mark Karlin.) Equal Voice organizations meet regularly and have formed task forces for the colonias working on health, jobs and economic security, education, housing, immigration and civic engagement. One example of the effectiveness of a strategic approach to empowerment in the colonias was a recent cumbre, or community summit meeting, convened by Equal Voice member La Unión del Pueblo Entero (LUPE), headed by United Farm Workers veteran Juanita Valdez-Cox.

Seifert wrote of the February summit:

This gathering of border neighborhood leaders who were union [founded in 1989 by César Chávez] members was being asked to decide the priorities for the next two years of work. It was quite a serious group of people. They were being asked to give up a precious Saturday morning. A free morning for an hourly-wage earner is as rare as a raise…. Hardworking people who, at the end of a week have very little change to count, understand very well the connection of daily bread and justice…. The delegates filed out of the auditorium, heading for their colonias and their homes, for the hard work that is living out a dream.

Juanita Valdez-Cox is the director of LUPE, founded by César Chávez. As a child, she traveled with her parents around the US as seasonal farm workers. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)Working Toward a Dream Does Not Mean Waiting for Perfection

Juanita Valdez-Cox is the director of LUPE, founded by César Chávez. As a child, she traveled with her parents around the US as seasonal farm workers. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)Working Toward a Dream Does Not Mean Waiting for Perfection

Working toward a dream does not mean sitting back and waiting until living conditions are perfect, according to one of the six guiding principles of ARISE (A Resource in Serving Equality), which has four colonia outreach centers in south Texas. Lourdes Flores, president of the main ARISE support center, emphasizes that the role of the organization is to provide services that help create independence. “We are animators,” she says. “We animate people and provide skills to help them become independent.”

Many of the key leaders in Equal Voice’s south Rio Grande Valley colonias initiative are women, but ARISE is specifically focused on empowering, “women to help other women see that they have talents and gifts that they can use to improve themselves, their families and their communities.” Its slogan is, “Changing a community, one woman at a time.”

Colonias adults and children lack recreational and exercise opportunities. Lourdes Flores, president of the main ARISE support center, and community organizer Ramona Casas galvanized local colonia residents to secure a 10-acre park. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)

Colonias adults and children lack recreational and exercise opportunities. Lourdes Flores, president of the main ARISE support center, and community organizer Ramona Casas galvanized local colonia residents to secure a 10-acre park. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)

“When a woman learns things, it empowers the whole family,” says ARISE community organizer Ramona Casas. “Women are more open to accepting change.” That may explain why, at the main support center, next to a new ten-acre park and exercise area, Flores and Casas point out with satisfaction ARISE’s development of inexpensive solar heaters, an organic gardening area and diverse educational programming.

By comparison, the slogan of Proyecto Azteca, located not far from the ARISE support center, could easily be, “Improving the colonias one home at a time.” With 0 percent interest loans and a requirement of 550 hours of sweat equity, a home can be built with staff assistance for as little as $45,000.

“The need for affordable housing is great,” says executive director Ann Cass. “Housing needs to be sustainable, as well, to survive the weather events that we have, including cross winds, hurricanes and wind storms.”

Ann Cass, executive director of Proyecto Azteca, with energy efficient wall insulation built into sweat equity sustainable housing. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)With other leaders of the colonias’ Equal Voice Network, Cass spends much of her time working to secure a fair share of funding from different levels of government. This includes tedious but necessary tasks such as ensuring an allocation of federal relief funds for Hurricane Dolly, which devastated the area. In this case, the coalition corralled $186 million for damage to the colonias’ housing and infrastructure, including $64 million for regional drainage improvement projects. Hopefully, with continued Equal Voice Network vigilance, this will lead to jobs for local residents and contractors.

Ann Cass, executive director of Proyecto Azteca, with energy efficient wall insulation built into sweat equity sustainable housing. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)With other leaders of the colonias’ Equal Voice Network, Cass spends much of her time working to secure a fair share of funding from different levels of government. This includes tedious but necessary tasks such as ensuring an allocation of federal relief funds for Hurricane Dolly, which devastated the area. In this case, the coalition corralled $186 million for damage to the colonias’ housing and infrastructure, including $64 million for regional drainage improvement projects. Hopefully, with continued Equal Voice Network vigilance, this will lead to jobs for local residents and contractors.

Developing the power to effect social change locally has ripple effects. Some of the south Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice organizations worked with a statewide coalition to defeat all 85 anti-Mexican immigration and anti-rights bills, including a voter identification law, proposed in the state legislature.

From Unscrupulous Opportunism to Pride and Empowerment

In Mexico City, a colonia is a neighborhood – regardless of income – that can represent a vibrant community. Turning US shantytowns born of the unscrupulous economic opportunism of landowners into communities of pride and empowerment is not an easy task. The obstacles are immense.

But it is being done in the south Rio Grande Valley of Texas, through the tenacious work of leaders, many of them US Latinas, who know that progress can be measured one streetlight at a time.

It is the creation of community itself – of neighbors uniting with a strong unwavering voice – that leads to the improvement of daily living standards and to a shared pride.

This empowerment fulfills the vision of César Chávez: “From the depth of need and despair, people can work together, can organize themselves to solve their own problems and fill their own needs with dignity and strength.”

“We are not able to retreat, we will overcome. We are winning, because ours is a revolution of the mind and the heart,” said César Chávez. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)

“We are not able to retreat, we will overcome. We are winning, because ours is a revolution of the mind and the heart,” said César Chávez. (Photo by Mark Karlin.)

The next installment of Truthout on the Mexican Border will be “Javier Sicilia: A Poet Leads the Mexican Peace Movement.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 432 new monthly donors in the next 7 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.