Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

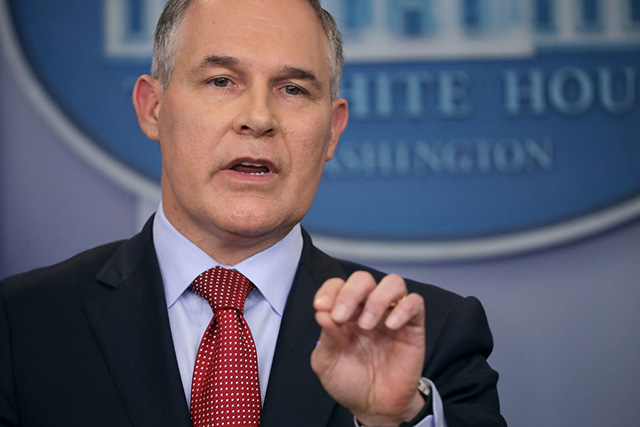

In June, about 10 weeks before explosions and fires would begin erupting at a chemical plant damaged by Hurricane Harvey near Houston, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt placed a 20-month delay on the implementation of rules designed to prevent and contain spills, fires and explosions at chemical plants.

In a public comment filed with the EPA in May, an association of emergency response planning officials asked that at least one portion of the rules be spared the delay and implemented immediately: a section requiring hazardous chemical facilities to coordinate with local first responders and planners in case of an emergency.

“Save for the act of coordination and providing certain information, if it exists, this provision simply and directly requires people to talk to each other,” wrote Timothy Gablehouse, president of the National Association of SARA Title III Program Officials, an association of state and local emergency response commissions. “It is fully appropriate for regulated facilities to understand what local responders can and cannot accomplish during an emergency response.”

Pruitt delayed implementation of the rules in response to complaints about the rulemaking process filed by chemical companies and industry groups, according to the EPA’s filing in the federal register. States with large industrial chemical sectors, including Texas and Louisiana, also requested that compliance dates for the rules be delayed.

The industry complained that the emergency response requirements in particular did not specify limits on the information that emergency planners and first responders could ask for, and the EPA agreed to delay those provisions to allow for additional public comment, despite warnings from Gablehouse and environmental groups.

The decision to delay the rules — particularly the section on sharing information with emergency planners — is under intense scrutiny as environmental disasters unfold in the wake of Hurricane Harvey.

“It’s offensive that they refuse to share information with police and firefighters who have to risk their lives to go into those disaster [areas],” said Gordon Sommers, an attorney at Earthjustice, an environmental group that opposed the delay. “They risk their lives because they don’t know what risks they face … because the industry does not want to share information.”

Toxic Fires in Texas

Early Thursday morning, emergency officials reported two explosions and black smoke coming from a chemical facility in Crosby, Texas, about 25 miles outside of Houston.

Arkema, the French company that runs the chemical facility, had warned that fires or explosions could occur at the plant because “unprecedented” flood waters had compromised backup power systems that kept stores of organic peroxide, a hazardous chemical, refrigerated at temperatures that prevent combustion.

Federal authorities warned that the resulting chemical fumes in Crosby are “incredibly dangerous,” and smoke from the plant left at least one first responder in need of medical treatment, according to The Washington Post.

In a statement released on Thursday, Arkema officials said that “organic peroxides are extremely flammable” and the company agrees with public officials that the best course of action “is to let the fire burn itself out.” Local residents should be aware that the chemicals are stored in “multiple locations” and the threat of “additional explosion” remains.

Hurricane Harvey has wreaked havoc across the vast petrochemical corridor that dominates Texas’ Gulf Coast, releasing millions of pounds of pollutants from refineries and chemical plants. The disaster raises immediate questions about the Trump administration’s ongoing effort to gut and delay environmental protections nationwide, including the amendments to the EPA’s “Risk Management Program” for accidental releases at chemical plants that Pruitt delayed in June.

Aging Infrastructure and Thousands of Accidents

The EPA began reviewing and updating the rules after several deadly explosions occurred at refineries and chemical facilities during the Obama administration, including an explosion at a chemical facility in West, Texas, that killed 15 people in 2013, according to Sommers. The agency looked at over 2,000 chemical accidents that occurred over a 10-year period and wrote new rules to prevent and contain releases of 160 extremely dangerous chemicals.

“I mean it’s inexcusable. People … are facing already all the catastrophe that is inherent in a major flood like this,” Sommers said. “It’s crazy that on top of that, they are also worried about explosions and chemicals spills and all sorts of chemicals being in the air because there aren’t backup systems in place.”

Federal law prevents the administration from unilaterally gutting regulations without taking comments from the public, so Pruitt and other federal Trump appointees have been using statutory loopholes to block or delay pending regulations at federal agencies instead of nixing them outright.

From January to mid-July, the administration blocked or delayed at least 45 federal regulations across several departments, many of them designed to reduce air and water pollution, according to the Center for Progressive Reform.

Jeff Ruch, director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, points out that President Trump revoked a Federal Flood Risk Management Standard put in place by President Obama just two weeks before Hurricane Harvey battered the Texas coast.

“If Trump had a smaller baseball cap, he could be like an ostrich and stick his head in the sand,” Ruch said.

Combined with the chemical rule delay, Ruch said, the Trump administration appears to be dismantling the federal government’s role in preventing disasters. Like public infrastructure, the nation’s private industrial infrastructure is aging and in disrepair. By setting aside federal regulations, the Trump administration is discouraging corporate investment in new infrastructure.

“We haven’t built a [new] refinery in 60 years, so these are really old facilities,” Ruch said.

Pruitt has also taken fire for ditching EPA plans to ban a pesticide linked to brain damage in children. Under orders from President Trump, federal agencies must make an effort to slash regulations, forcing the EPA to consider gutting rules that protect children from lead poisoning along with other longstanding protections.

As promised, environmental groups and other watchdogs have filed lawsuits challenging Trump and Pruitt’s deregulatory agenda, and courts are starting to place limits on the administration’s power. For example, last month, a federal court ruled that the EPA could not delay a rule that limits the amount of climate-warming methane oil and gas drillers can spew into the atmosphere.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.