Truthout is an indispensable resource for activists, movement leaders and workers everywhere. Please make this work possible with a quick donation.

Carrying palm fronds and flowers, women and children walked into the center of town along roads strewn with fallen mangos. Blue-crowned motmots flitted from tree to tree while a pandemonium of parakeets flew past overhead, punctuating the quiet morning with their raucous squawking. It was nearly time for Palm Sunday celebrations, but people were also congregating to determine the future of their territory, nestled in the mountains of the Chalatenango department in northern El Salvador.

The population of Nueva Trinidad voiced its resounding opposition to mining in an official municipal consultation process on March 29. In seven community voting centers, 99.25 percent of participating registered voters cast their ballots against metallic mining in Nueva Trinidad. The third consultation of its kind in the country, the local exercise in participatory democracy is the latest manifestation of the thriving national movement against mining in the small Central American nation.

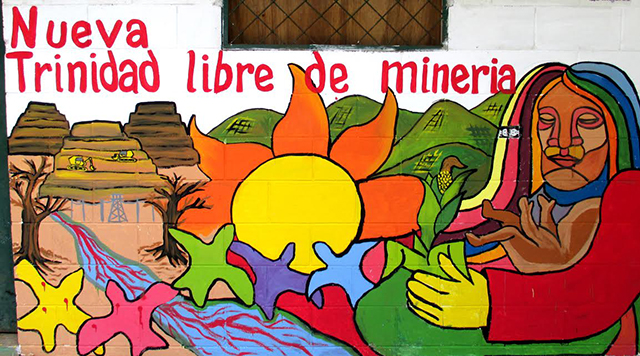

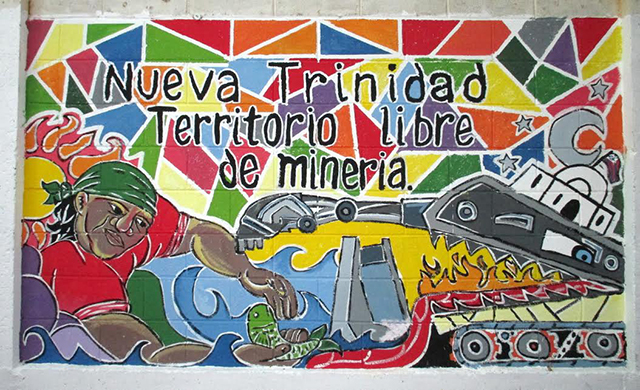

The department of Chalatenango has been at the forefront of the national movement against mining in El Salvador. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The department of Chalatenango has been at the forefront of the national movement against mining in El Salvador. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

“We defend the territory by any means necessary here,” said Ana Dubón, youth secretary of CCR, the Association of Communities for the Development of Chalatenango.

CCR is one of the organizations working on the campaign for territories free of mining in the region. El Salvador is comprised of 14 administrative divisions called departments, but political power resides with the elected governments at the national and municipal levels.

Affected communities employed a diversity of tactics, from marches and rallies to direct action and sabotage.

The importance of the municipal consultation process isn’t limited to the consultation itself, Dubón told Truthout. CCR and other community-based groups working in the region have been engaging in community organizing and awareness-raising activities throughout Chalatenango on an ongoing basis. They’ve had support from the National Roundtable against Metallic Mining, a coalition of community-based, social movement and nonprofit organizations.

Nueva Trinidad is the third municipality in El Salvador to hold a consultation on mining. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Nueva Trinidad is the third municipality in El Salvador to hold a consultation on mining. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

“We organize forums, discussions, meetings, workshops – everything on the issue of mining so that communities are more empowered in their understanding of the consequences mining exploration and exploitation would bring,” said Dubón. “We come together as different sectors to offer an aware, empowered point of view about the defense of our territory.”

Mining companies arrived in Chalatenango roughly 10 years ago, when two Canadian companies began exploration in the region. Ten municipalities in the department, including the three that have now held consultations, have been directly affected by mining concessions.

“Ever since the threat [of mining] arose years ago, we began thinking of different strategies for how to defend ourselves. In the beginning it was organized and peaceful struggle, with marches, rallies, and that kind of thing,” said Julio Rivera, a resident of Nueva Trinidad and a member of the local consultation promotion committee.

Affected communities employed a diversity of tactics, from marches and rallies to direct action and sabotage. They successfully kicked the mining companies out, but they want to make sure they never come back. A moratorium on mining has been in place in El Salvador since 2008, but it’s just an administrative policy. Proposals for a legislated permanent ban on mining have stagnated in Congress.

“Organized struggle is very important, but what was needed was legal backing. And the Municipal Code provides for that for us,” said Rivera.

Women and youth took on key roles at the community voting centers in Nueva Trinidad. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Women and youth took on key roles at the community voting centers in Nueva Trinidad. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The Municipal Code of El Salvador stipulates that if 40 percent of the registered voters in any given municipality petition the municipal council for a public consultation on an issue of local concern, the municipal government must comply. Until last year, however, the mechanism hadn’t been invoked.

Between 1980 and 1992, an estimated 75,000 people were killed in El Salvador, and another 8,000 disappeared.

San José Las Flores set the precedent. On September 21, 2014, more than 99 percent of participating registered voters in the municipality voted no to mining in the first consultation of its kind in the country. San Isidro Labrador was next on November 23, 2014, with similar results. In each of the three consultations held to date, more than 60 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot. The end result of the process is an official municipal ordinance declaring the territory free of mining.

Fifty people from different parts of the country participated in the consultation process in Nueva Trinidad as national observers. Twenty-four international observers from Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, the United States, Canada and England also accompanied the event, bearing witness to the activities throughout the day at the various voting centers.

Felipe Orellana rested on his wooden gate as he watched a group of observers gathered for a training session up the street at the community hall in Carasque, a village in the municipality of Nueva Trinidad.

“I see it as a good thing,” he said of the consultation. Now 85, Orellana doesn’t have much energy to continue harvesting oranges, raising farm animals or growing corn and other subsistence crops, but he wants to protect the local way of life from harm. Mining could damage or pollute the area, he said. “For us, it would mean even greater poverty.”

Felipe Orellana, 85, is worried mining would displace local residents. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Felipe Orellana, 85, is worried mining would displace local residents. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Most of all, though, Orellana doesn’t want anyone to be forced to leave their homes and lands again. In the 1980s, he spent three years and three months away from home in another part of Chalatenango. His neighbors also fled due to the indiscriminate violence carried out by state armed forces against civilians in the midst of the armed conflict between the government and the guerrilla forces comprising the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN).

Between 1980 and 1992, an estimated 75,000 people were killed in El Salvador, and another 8,000 disappeared. A United Nations Truth Commission reported that of the thousands of complaints and testimonies received concerning extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, torture and other serious acts of violence, “those giving testimony attributed almost 85 percent of cases to agents of the state, paramilitary groups allied to them, and the death squads.” In comparison, approximately 5 percent of cases were attributed to the FMLN. Amnesty International estimated that state security forces killed 16,000 civilians in 1981 alone.

During the 12-year armed conflict, the United States provided more than $6 billion in economic and military aid to the Salvadoran government and armed forces.

Julio Rivera witnessed the worst of the conflict. He is a survivor of the May 14, 1980, Sumpul River massacre. Seven years old at the time, Rivera hid nearby while more than 600 children, women and men were brutally murdered by soldiers, national guardsmen and paramilitaries on the banks of the Sumpul River, which marks the Salvadoran-Honduran border in Chalatenango.

It is in part Chalatenango communities’ experience of forced displacement that informs their struggle to keep mining companies out at all costs.

The area was a stronghold for the FMLN, and military forces carried out scorched earth operations, targeting both guerrilla forces and noncombatant communities. Indiscriminate aerial bombings, military and paramilitary incursions, and extrajudicial executions became the norm in the early 1980s. Tens of thousands of Chalatenango residents fled to other areas of El Salvador, refugee camps in southwestern Honduras and North America. Approximately one-quarter of the country’s population was displaced during the conflict. Entire communities were deserted.

A bomb sits on display at the Museum of the Salvadoran Revolution in Perquín. Behind it, the crater of a 500-pound, US-made bomb, dropped in 1982, is still visible. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

A bomb sits on display at the Museum of the Salvadoran Revolution in Perquín. Behind it, the crater of a 500-pound, US-made bomb, dropped in 1982, is still visible. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, groups of displaced Salvadoran civilians returned to resettle abandoned communities. When Rivera and others arrived in the small town of Nueva Trinidad on March 22, 1991, there was almost nothing left.

“There wasn’t a single house here. There were fragments from where a house once stood – pieces of a wall, or fallen wood. But the houses here were either bombed by planes, burned by the army, or just fell apart with the rain over time,” said Rivera. “Everything was completely destroyed.”

Little by little, the returnees rebuilt Nueva Trinidad. It is in part the Chalatenango communities’ experience of forced displacement that informs residents’ struggle to keep mining companies out at all costs.

“With all the gold they extracted, they could have at least left us with some kind of potable water system.”

Elsewhere in El Salvador, communities continue to suffer the devastating impacts of international mining company operations. One hundred miles east of Nueva Trinidad, the San Sebastian gold mine operated for more than 100 years. Its last owner, Wisconsin-based mining company Commerce Group Corp, effectively abandoned the site after decades of extraction. The company’s permit was revoked in 2006, following environmental studies conducted by the Salvadoran government.

Acid mine drainage continues. A mile or so downstream from the mine site, the San Sebastian River and the streams that feed it are a deep orange color. Rocks in the river are coated with a white and yellow crust. In 2012, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources found that the river contained nine times more cyanide than is permitted by the national standards for potable water. The river’s iron content was more than 1,000 times the limit.

The iron content of waterways downstream of the San Sebastian mine is 1,000 times the maximum level permitted by national potable water standards. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The iron content of waterways downstream of the San Sebastian mine is 1,000 times the maximum level permitted by national potable water standards. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Standing above the orange waters, local villager Gustavo Blanco explained that, with another month left in the dry season, the situation will likely become even more extreme before the rains begin. Sometimes, he said, the river runs red.

Groundwater in the area is also contaminated. “When well water is poured into a container, a white crust forms,” said Blanco. Communities in the area have no local access to clean surface or groundwater. “With all the gold they extracted, they could have at least left us with some kind of potable water system.”

Villagers have to pay if they want clean water for consumption or household use. A gallon or so of drinking water goes for 50 cents. A barrel of water for bathing, laundry and other household needs costs $3, and large tanks are available for $20.

“The most we earn around here is $6 a day,” said Blanco. There are hardly any jobs in the area, and not everyone can afford water. Those who don’t have the resources to buy water use river or well water. Many locals suffer from health problems, particularly those who worked in the mine, said Blanco.

“The company simply left. . . . leaving behind only contaminated water and lands,” he said. “They didn’t leave any benefit for us, just illnesses.”

After it failed to receive a permit to continue mining, Commerce Group Corp initiated proceedings against El Salvador at the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a supranational arbitration tribunal belonging to the World Bank Group. The case and a subsequent review were both unsuccessful, but for monetary and procedural reasons rather than on the basis of the case’s merits.

The Vancouver-based Pacific Rim mining corporation also filed an ICSID lawsuit against El Salvador in 2009, after the permit for operations at its El Dorado gold mining project didn’t come through. Both Pacific Rim and Commerce Group Corp cited provisions in the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) and Salvadoran investment protection legislation as the legal basis for their cases. In the case of Pacific Rim, now a subsidiary of Canadian-Australian corporation OceanaGold, ICSID ruled against the application of CAFTA, but allowed the $301 million lawsuit to proceed on other grounds. A final ruling is expected any time.

Stalled for seven years, the El Dorado project continues to be a source of tension in the department of Cabañas. Communities are divided, and grassroots community environmental groups have suffered threats and violence. In 2009, Marcelo Rivera, Ramiro Rivera and Dora Recinos Sorto, all local activists campaigning against the mine, were murdered. Recinos Sorto was eight months pregnant at the time. Despite their tragic loss, local groups continue to organize to defend their lands and communities.

“We’re going on almost 10 years of struggle against this transnational company,” said Vidalina Morales, an outspoken local community leader. “I think it’s a very inspiring sign that Chalatenango is at the forefront of these consultations,” she said. “We hope to hold them here in Cabañas too in the near future.”

Back in Nueva Trinidad, where Morales participated as a national observer, the consultation process had an unanticipated showing of government support. Among those present were Arístides Valencia, minister of the Interior and Territorial Development; Marcos Rodríguez, secretary of Citizen Participation, Transparency and Anti-Corruption; Audelia Guadalupe López, congresswoman for Chalatenango; José Raimundo Alas, governor of Chalatenango; and representatives of the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman.

Also present were mayors and councilors from neighboring municipalities, including San José las Flores and San Isidro Labrador, where the first two consultations were held. Together with Nueva Trinidad, the three municipalities form a small contiguous territory in eastern Chalatenango, and another addition to the block may be on the horizon. José Alberto Avelar, the mayor of Arcatao, publicly announced his interest in holding a consultation on mining in Arcatao, which borders Nueva Trinidad.

“The struggle continues to make progress,” said Morales. “I think we can speak of a triumph of the people of El Salvador: the fact that to date, there is still no mining in El Salvador.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 379 new monthly donors in the next 6 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.