On June 21, 2014, formerly incarcerated women, family members and advocates gathered in Washington, DC for the FreeHer rally to draw attention to the mass incarceration of women and to demand their freedom.

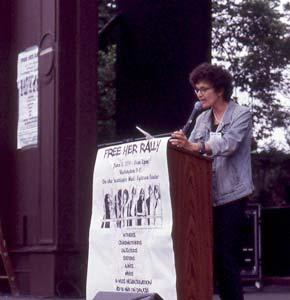

Dorothy Gaines, who received executive clemency from President Clinton, traveled from Alabama to Washington, DC, to speak at the Free Her rally. (Photo: Victoria Law)“This was the year I was due to be released,” said Dorothy Gaines on a drizzly Saturday afternoon in Washington, DC. In 1995, Gaines was sentenced to 19 years in prison. She was placed on a plane and flown from Alabama, where she had lived with her three children, to Connecticut where she entered the federal women’s prison at Danbury. “I’d never flown before,” she told Truthout. “My first flight was with US marshals on Delta.”

Dorothy Gaines, who received executive clemency from President Clinton, traveled from Alabama to Washington, DC, to speak at the Free Her rally. (Photo: Victoria Law)“This was the year I was due to be released,” said Dorothy Gaines on a drizzly Saturday afternoon in Washington, DC. In 1995, Gaines was sentenced to 19 years in prison. She was placed on a plane and flown from Alabama, where she had lived with her three children, to Connecticut where she entered the federal women’s prison at Danbury. “I’d never flown before,” she told Truthout. “My first flight was with US marshals on Delta.”

Gaines refused to accept either the distance from her children or the length of her sentence. She fought to be moved to a federal prison closer to her children while simultaneously fighting her case. She succeeded in both; two years after she began her sentence, she was moved to the federal prison in Tallahassee, Florida. Three years after that, in 2000, she received executive clemency from then-President Clinton and was released from prison.

Fourteen years later, Gaines traveled from Alabama to Washington, DC, to add her voice and experience to the FreeHer rally. She was not the only person. Approximately 300 people gathered that rainy Saturday afternoon to demand an end to mass incarceration and to push for the release of hundreds of other women caught in the drug war.

“Conceived in the Belly of the Beast”

“When I left our sisters in prison, I told them that we would not forget them,” said Andrea James, co-founder of Families for Justice as Healing and organizer of the Free Her rally. (Photo: Victoria Law)The idea began in the prison yard at the Federal Correctional Institution at Danbury, the women’s federal prison made famous by “Orange is the New Black” (which is where Gaines served her prison sentence). At a table in the yard, five women formed Families for Justice as Healing. “I was surrounded by women serving long sentences,” recalled Andrea James, who spent a year and a half in prison. “They were separated from their children, their families and their communities.” Ironically, the impetus to form Families came from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which brings together state legislators and corporations to draft model legislation, including mandatory minimum sentencing laws as well as laws like Florida’s Stand Your Ground statute. “I couldn’t think of an existing organization like this that mass-produced legislation working on the side of the people,” James said. From that absence, Families for Justice as Healing was born.

“When I left our sisters in prison, I told them that we would not forget them,” said Andrea James, co-founder of Families for Justice as Healing and organizer of the Free Her rally. (Photo: Victoria Law)The idea began in the prison yard at the Federal Correctional Institution at Danbury, the women’s federal prison made famous by “Orange is the New Black” (which is where Gaines served her prison sentence). At a table in the yard, five women formed Families for Justice as Healing. “I was surrounded by women serving long sentences,” recalled Andrea James, who spent a year and a half in prison. “They were separated from their children, their families and their communities.” Ironically, the impetus to form Families came from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which brings together state legislators and corporations to draft model legislation, including mandatory minimum sentencing laws as well as laws like Florida’s Stand Your Ground statute. “I couldn’t think of an existing organization like this that mass-produced legislation working on the side of the people,” James said. From that absence, Families for Justice as Healing was born.

“We wanted to have a huge public event to raise our voices and raise awareness of all the women inside who are separated from their families and their communities.”

During their in-prison meetings, the women realized the need to draw public attention to the mass incarceration of women. “We wanted to have a huge public event to raise our voices and raise awareness of all the women inside who are separated from their families and their communities,” said James. “We want people to think about what happens to children and communities when a woman is incarcerated. We also want to let the legislative and executive branches know that people are paying attention. These are people we care about. These are people who are part of our families and communities.”

Andrea James and Susan Rosenberg, both of whom spent years incarcerated at FCI Danbury (Photo: Victoria Law)The idea grew into the FreeHer rally held on June 21 in Washington, DC. For the past two years, James traveled around the country meeting with formerly incarcerated women, family members and advocates. “When I left our sisters in prison, I told them that we would not forget them,” James said at the rally. “I made them a promise that we would not forget them.”

Andrea James and Susan Rosenberg, both of whom spent years incarcerated at FCI Danbury (Photo: Victoria Law)The idea grew into the FreeHer rally held on June 21 in Washington, DC. For the past two years, James traveled around the country meeting with formerly incarcerated women, family members and advocates. “When I left our sisters in prison, I told them that we would not forget them,” James said at the rally. “I made them a promise that we would not forget them.”

The FreeHer rally is part of that promise as well as a way to visibly raise awareness about women’s incarceration and its impact on families and communities. In April, the Obama administration announced it would review the sentences of federal drug war prisoners for possible commutation.

That same day, The New York Times announced that bipartisan Congressional bills to reform sentencing have stalled. One would have reduced the lengthy sentences for those convicted of low-level drug offenses while the other would award credit toward early release for those prisoners considered low-risk if they participate in job training or drug treatment programs.

The FreeHer rally, which included women who had received executive clemency under previous presidents, reminded the crowd that, while legislation is important to ending mass incarceration, executive clemency, sentence commutations and sentence reductions are all within the president’s power and can be exercised now.

Why FreeHer?

Since 1980, the rate of women’s incarceration has increased 518 percent (while the rate for men increased 230 percent). Less than 13,000 women were in prison in 1980. By the end of 2012, that number had risen to over 108,000 (not including the 102,000 women in local jails). Women of color are disproportionately impacted: the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that black women had an imprisonment rate of nearly three times that of white women. The incarceration rate for Latinas is nearly twice that of white women.

No one understands the impact of the drastic surge of women’s imprisonment better than those who have spent time behind bars. At the FreeHer rally, they drew on their own experiences to call for an end to the policies and practices that lock so many women behind bars.

“Prisons are designed for men; health care is designed for men; programs are designed for men. Women deserve to be recognized.”

Beatrice Codianni spent 15 years in Danbury. She remembers how women were treated by the legal system and in the prison system. “The war on drugs did so much damage to men and to women, but we never hear about the women,” she told Truthout. “We wanted to focus on women because they get the short end of the stick. Prisons are designed for men; health care is designed for men; programs are designed for men. Women deserve to be recognized.” Codianni, who is now managing editor for the information site Reentry Central, adds that reentry programs are also primarily focused on men. “You don’t see a lot of programs with childcare so that women can attend. Job training programs and drug treatment are also geared towards men.”

“Women are the backbone of families and communities,” Gaines told Truthout. “There are too many women serving time.” Reflecting on her own case, she added, “We [women] don’t have any information to give the government [in exchange for a lesser sentence]. We get the bulk of the time . . . We need to bring awareness that women need to be released. We don’t need to wait 10, 15, 20 years to let them go.”

Sixty-two percent of women in prison are mothers, many to children under the age of 18. Codianni arrived at Danbury in 1995, shortly after it had  Lashonia Etheridge’s children were ten months old and three years old when she went to prison. They were twenty-one and twenty-three years old when she was released. (Photo: Victoria Law)been converted to a women’s prison. “I was fortunate that my youngest child was 16 when I went to prison,” she said. “But other women had babies or young children.” Lashonia Etheridge, the rally’s mistress of ceremonies, was one of those mothers. Her children were 10 months old and three years old when she went to prison. They were 21 and 23 years old when she was released. “You can imagine the challenges we face when we reunite with our children.” Andrea James had a six-month-old son when she arrived at Danbury. “She handed him to her husband in the lobby of the prison,” James’ mother, Dolores Alleyne Goode, told Truthout.

Lashonia Etheridge’s children were ten months old and three years old when she went to prison. They were twenty-one and twenty-three years old when she was released. (Photo: Victoria Law)been converted to a women’s prison. “I was fortunate that my youngest child was 16 when I went to prison,” she said. “But other women had babies or young children.” Lashonia Etheridge, the rally’s mistress of ceremonies, was one of those mothers. Her children were 10 months old and three years old when she went to prison. They were 21 and 23 years old when she was released. “You can imagine the challenges we face when we reunite with our children.” Andrea James had a six-month-old son when she arrived at Danbury. “She handed him to her husband in the lobby of the prison,” James’ mother, Dolores Alleyne Goode, told Truthout.

But even older – and grown – children are affected by parental incarceration. Ariel Goode, James’ oldest daughter, was in her mid-20s when her mother was sent to prison. “When she went away, that was traumatic,” she told Truthout. “Going through my twenties without her was so hard. I couldn’t pick up the phone when I needed her.”

Karla Bowyer, who works with Amachi, a Pittsburgh organization supporting youth with incarcerated parents, also remembers the effects of her mother’s incarceration. Her mother, struggling with addiction, was in and out of jail during Bowyer’s childhood. “I know what it’s like to be suddenly separated from your mother,” she told the crowd. But, she acknowledges, unlike the women that FreeHer is focusing on, her mother did not serve one long prison sentence. “She was gone often, but she wasn’t gone for years at a time, so I could consider myself fortunate that my mother returned home after a short time.”

Once inside the prison, women did not give up hope for an early release. Many not only hoped, but actively worked toward making that hope a reality. In an interview with Truthout before the rally, Codianni remembered how women went through what she described as a “grueling process” to request clemency. “They’d put in the paperwork and wait and wait and wait. And pray. And they’d hear nothing. Or they’d be denied. Then they’d try again the next year. They got the same thing ad nauseam.”

A lifelong educator, Matthew Goode connects the slave patrols of the antebellum South with the current-day system of policing and prisons. “It’s a continuum. People need to understand that.”

Codianni recounted the high hopes women had when Obama was elected in 2008. “We watched all the debates and cheered Obama on,” she said. “I remember the night he was elected. I was sitting in the TV room with so many women. We were so excited and we had such high hopes. We gathered around the TV and, when the results were announced, the women just roared. They, me, everyone was so excited. We said, ‘Now we will have a president who will change these draconian mandatory sentences.’ We had so much hope.” She paused. “Then reality set in. The same thing happened when Holder was appointed. We had high hopes then too [but nothing has changed].”

“We want lawmakers to see that what they’ve done has failed,” said Starlene Patterson. “Yes, it’s failed.” Patterson spent eight years in the federal prison system, mostly at Danbury. Patterson has been out of prison for the past seven years, but remains passionate about the issue. She also sees this year as a window of opportunity to push the issue. “Obama’s changing the commutation requirements; he reduced the crack-cocaine [sentencing] disparity. Holder’s becoming passionate about incarceration issues. There’s some conversation going on [among lawmakers] whereas before, there was no conversation. We have to fight. If we don’t, we can’t get no results.”

The majority of the day’s speakers focused on the number of women incarcerated for nonviolent crimes under the widening net of the war on drugs. KC Mackey of Black and Pink, an organization that supports LGBTQ people behind bars, reminded attendees about the existence and reality of trans women, many of whom are incarcerated in men’s prisons. Mackey read excerpts of letters from three trans women that Black and Pink currently works with. “I hear so many stories of heartache and loneliness and abuse that never seem to end with a mention of support,” said a letter from Nina, a trans woman currently incarcerated in California. “So I challenge any and everyone who is reading this: Find peace and comfort with those who are LGBTQ in your prison, embrace them and help each other with your struggles.”

(Photo: Don Rojas)

(Photo: Don Rojas)

Women charged with violent crimes were not entirely excluded. In addition to numerous signs in support of Marissa Alexander, representatives of Boston Feminists for Liberation spoke about the need to support women incarcerated for self-defense, specifically highlighting the cases of Alexander as well as those of the New Jersey Four and CeCe McDonald, all of whom are black women who were incarcerated for defending themselves against attack.

“I had to go back inside to tell the long-termers, ‘Never give up.'”

Among the 300 attendees were James’ parents, husband and children. “We took the Megabus from Boston,” James’ father, Matthew Goode, told Truthout. “I’m 84 and Dolores [James’ mother] is 80. I’m telling you this to show that people can get places. You don’t need airfare or lots of money to be able to come out and support.” A lifelong educator, Goode connects the slave patrols of the antebellum South with the current-day system of policing and prisons. “It’s a continuum. People need to understand that.”

Angela Murphy, who lives nearly 180 miles away in Hampton, Virginia, said she had only learned about the rally the day before. “I got an email, turned to my best friend and said, ‘It’s time to go.'” Murphy spent several years in and out of the state prison system and has experienced the lack of support for people returning home from prison. “I went to after help to get no help,” she said. If there had been resources available, she continued, “I wouldn’t have been going back and forth for so long.” Murphy is attempting to change that lack, at least in Hampton, with House of Dreams, an outreach ministry dedicated to helping people returning from jails and prisons. “My goal is to let people know they can make a change,” she said.

“I Actually Won the Demand That We’re Making Today . . . Every One of the People Inside Deserves the Same Chance”

“I actually won the demand that we’re making today,” said Susan Rosenberg, who spent sixteen years in the federal system before Clinton released her on his last day in office. (Photo: Victoria Law)“I actually won the demand that we’re making today,” said Susan Rosenberg, who spent 16 years in the federal system before being granted a pardon during then-President Clinton’s last day in office. She learned that she had been granted a pardon while in the legal visiting room at FCI Danbury. She argued with the warden to allow her to return to her housing unit to say goodbye. “I had to go back inside to tell the long-termers, ‘Never give up,'” she told the crowd. “Every one of the people still inside deserves that same chance. Some of the women that I went to say goodbye to are still in prison.

“I actually won the demand that we’re making today,” said Susan Rosenberg, who spent sixteen years in the federal system before Clinton released her on his last day in office. (Photo: Victoria Law)“I actually won the demand that we’re making today,” said Susan Rosenberg, who spent 16 years in the federal system before being granted a pardon during then-President Clinton’s last day in office. She learned that she had been granted a pardon while in the legal visiting room at FCI Danbury. She argued with the warden to allow her to return to her housing unit to say goodbye. “I had to go back inside to tell the long-termers, ‘Never give up,'” she told the crowd. “Every one of the people still inside deserves that same chance. Some of the women that I went to say goodbye to are still in prison.

“What would happen if Obama released 3,000 women incarcerated for the war on drugs?” she asked the crowd. “They would come home. They would rebuild their lives and grow their communities.” She reminded the audience that executive clemency, sentence commutations and sentence reductions are all within Obama’s power and do not need legislative approval. “But we have to remember the quote from Frederick Douglass: ‘Power concedes nothing without a demand.'”

For Gaines, the day was emotional. Her son was 9 years old when she was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Last week, that same son was sentenced to 20 years in state prison, leaving behind an 8-year-old daughter. “Instead of being in prison, I should have been home with him,” she told the crowd. “This cycle has got to stop.”

Andrea James and her eldest daughter, Ariel Goode (Photo: Victoria Law)

Andrea James and her eldest daughter, Ariel Goode (Photo: Victoria Law)

5 Days Left: All gifts to Truthout now matched!

From now until the end of the year, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar up to $50,000! Thanks to a generous supporter, your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

We have just 5 days left to raise $50,000 and receive the full match.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. As Trump attempts to silence dissenting voices and oppositional nonprofits, reader support is our best defense against the right-wing agenda.

Help Truthout confront Trump’s fascism in 2026, and have your donation matched now!