Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

In October 1990, only months after being transferred to Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit (SHU), Todd Ashker was shot in the right wrist by a prison guard. “This nearly severed my hand from my wrist and caused severe damage to hand, wrist and forearm,” he recounted. Ashker stated that he was denied medical care, including pain management, and was told by medical staff, “If you want better care, get out of SHU. It’s your choice.” Only after he won a court injunction in February 2010 was he given an arm brace and physical therapy. [Letter from Todd Ashker, November 13, 2011.] Ashker’s experience is the norm rather than the exception. “Prisoners with medical concerns are routinely told by prison officials that if they want better medical care for their conditions or illnesses, or improved pain management, the way to obtain adequate care is to debrief,” states a federal lawsuit filed by Ashker and other SHU prisoners.

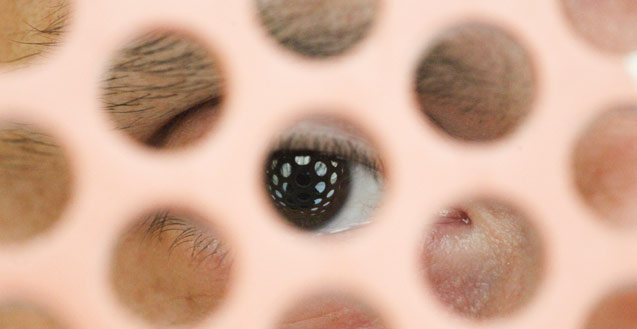

On July 1, 2011, Ashker and thousands of other prisoners went on hunger strike to protest such draconian conditions. As reported in Truthout last year, for three weeks, at least 1,035 of the 1,111 inmates locked in the SHU refused food. In the SHU, which comprises half of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison, prisoners are locked into their cells for at least 22 hours a day. Over 500 people have been confined in the SHU for over a decade, over 200 for more than 15 years and 78 for over 20 years. The only way that a person can be released from the SHU is to debrief, or provide information incriminating other prisoners. Even those who are eligible for parole have been informed that they will not be granted parole so long as they are in the SHU. “They are told they can debrief or die,” stated Jules Lobel, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, which recently filed a federal class-action lawsuit on behalf of the SHU prisoners. [Press conference by phone, May 31, 2012.]

The Pelican Bay hunger strike spread to 13 other state prisons and, at its height, involved at least 6,600 people incarcerated throughout California.

“We have decided to put our fate in our own hands. Some of us have already suffered a slow, agonizing death in which the state has shown no compassion toward these dying prisoners.” Mutope DuGuma, one of the hunger strike representatives, wrote in the original announcement for the hunger strike. “No one wants to die. Yet under this current system of what amounts to immense torture, what choice do we have? If one is to die, it will be on our own terms.”

The hunger strikers at Pelican Bay issued five core demands:

- Eliminate group punishments for individual rules violations;

- Abolish the debriefing policy and modify active/inactive gang status criteria;

- Comply with the recommendations of the 2006 US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons regarding an end to long-term solitary confinement;

- Provide adequate food;

- Expand and provide constructive programs and privileges for indefinite SHU inmates.

In September, when the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) failed to address these demands, prisoners resumed their hunger strike. The strike spread to 12 prisons inside California as well as to prisons in Arizona, Mississippi and Oklahoma that housed California prisoners. On October 13, prisoners at Pelican Bay ended their nearly three-week hunger strike after the CDCR guaranteed a comprehensive review of every prisoner in California whose SHU sentence is related to gang validation under new criteria. Two days later, hunger strikers at Calipatria State Prison stopped their strike to allow time to regain their strength.

Hunger strikers were issued write-ups for “leading a riot or strike or causing others to commit acts of force and violence,” stated a hunger strike representative. [Letter from Paul Redd, December 29, 2011.] The CDCR threatened to refer these cases to the local district attorney for outside prosecution; if found guilty, the hunger strikers would receive additional sentences. Ultimately, however, the charges were dropped.

In the following months, three hunger strike participants committed suicide: Johnny Owens Vick and Alex Machado were both confined in the Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit; Hozel Alanzo Blanchard was confined in the Calipatria Administrative Segregation Unit (ASU). Many of the hunger strikers blame the agonizing conditions in the SHU and ASU for the men’s deaths: “Obviously these men could not stand it anymore and preferred to die by their own hand rather than be subject to another minute of torture,” declared Todd Ashker. [Letter from Todd Ashker, December 26, 2011.]

In late December 2011, prisoners at California’s Corcoran State Prison’s ASU launched a hunger strike. They issued 11 demands, including adequate access to the law library and legal assistance and an end to the practice of holding prisoners in ASU after they have served their sentences in the unit. Prison staff transferred those who were identified as hunger strike leaders to the psychiatric ward and issued all participants violation notices for “participation in mass disturbances.” In February 2012, 27-year-old Christian Gomez died a week after joining the hunger strike.

In March 2012, the CDCR released its plan around SHU classification. The plan proposed identifying prisoners as part of Security Threat Groups (STGs) and placing them in SHU. It did not specify alternatives to debriefing for release from the SHU; instead, it offered a vague four-year plan.

Pelican Bay hunger strikers rejected the proposal: “The tools are still in place to keep us in the SHU indefinitely and, in some cases, they are planning on expanding this abuse by making it even more inclusive of a broader class of people with no end in sight,” explained hunger striker Lorenzo Benton. [Letter from Lorenzo Benton, June 5, 2012.] By designating people as part of STGs, the proposal expands the number of people who can be placed in the SHU. The proposal also continues the CDCR’s current policy of keeping alleged gang members in SHU indefinitely and does not respond to hunger strikers’ first three demands. Furthermore, noted Benton, “there does not exist any physical structural changes within our environment. We are still housed in an isolated environment for a prolonged period of time with hardly any meaningful contact.” [Letter from Lorenzo Benton, March 27, 2012.] Benton conceded that “a few creature comforts were bestowed upon us to pacify the masses, but our struggle is not about making prison more comfortable. It’s about being treated humanely and with the hope of a positive future.” [Letter from Lorenzo Benton, June 5, 2012.]

The hunger strikers issued their own counterproposal entitled the Modern-Management Control Unit (MMCU). Modeled after the Max-B management control unit programs in the 1970s and 1980s, the MMCU calls for the end of relying solely on confidential informants for SHU placement and using activities such as group petitions, birthday cards etc. as evidence of gang affiliations. In addition, it outlines a three-phase process for SHU release without requiring debriefing.

Hunger striker Mutope DuGuma stated that, at a follow-up meeting with hunger strikers and the mediation team, the CDCR representative “indicated that they’re going ahead with their proposal regardless of our counterproposal.” [Mutope DuGuma, May 28, 2012.] Instead, the CDCR has placed its proposal into the state’s revised budget.

However, DuGuma and others have not lost hope. “We are still going strong,” he stated. “We are working constantly, prisoners and the mediation team. Our five core demands have not been implemented [and] we all signed on to fight till they are.” [Letter from Mutope DuGuma, May 28, 2012.]

On March 20th, 400 prisoners in California’s SHUs and ASUs petitioned the United Nations to intervene on behalf of the more than 4,000 prisoners similarly situated. The petition can be downloaded from here. Five months earlier, in October 2011, shortly after the hunger strikes ended, Juan Mendez, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Torture, presented a written report on solitary confinement in the US to the UN General Assembly’s Human Rights Committee. He stated that solitary confinement “can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pretrial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles. Segregation, isolation, separation, cellular, lockdown, supermax, the hole, secure housing unit … whatever the name, solitary confinement should be banned by states as a punishment or extortion (of information) technique.” He called for a ban on any type of solitary confinement exceeding 15 days.

On May 31, the Center for Constitutional Rights filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court on behalf of those who have spent between ten and 28 years in Pelican Bay’s SHU, including the hunger strikers. The suit, Ruiz v. Brown, names ten plaintiffs and seeks to establish two classes of prisoners entitled to relief. The larger class consists of all prisoners serving indefinite SHU terms based on gang validation. The suit argues that their rights to due process are violated by this review process. The current review process consists of three steps: First, the prisoner is urged to debrief. Second, a mental health staff member asks, “Do you have a history of mental illness? Do you want to hurt yourself or others?” Third, the classification committee “reviews” the paperwork in the prisoner’s file. However, unless the prisoner is willing to debrief, the review allows no possibility of release from the SHU even though many have had no serious rule violations during their confinement.

The subclass consists of over 500 prisoners who have been or who will be confined to the SHU for ten years or longer. The suit argues that their prolonged SHU confinement violates their Eighth Amendment right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment, including:

- the cumulative effect of prolonged solitary confinement, notably psychological pain and suffering as well as “significant risk of future debilitating and permanent mental illness and physical harm”

- the denial of good-time credits and parole

- the deprivation of quality medical care

The plaintiffs seek a court injunction ordering the governor and the CDCR to present a plan within thirty days of the court order which:

- Provides for the release from the SHU of those confined for more than ten years

- Changes SHU conditions so that prisoners are no longer subject to isolation, sensory deprivation, lack of social and physical human contact and environmental deprivation

- Meaningful review of the continued need for SHU confinement of all prisoners in the SHU both currently and in the future

Nunn noted that, although the suit is limited to the SHU at Pelican Bay, any court ruling would affect the conditions and increasingly routine use of solitary confinement in other prisons. [Press conference by phone, May 31, 2012.]

The actions of both prisoners and outside allies have led to widespread attention to the issue of solitary confinement. Prisoner hunger strikes protesting extreme conditions have also erupted in Illinois, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia.

On June 19, 2012, the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Human Rights held the first-ever Congressional hearing on solitary confinement. In his opening statements, Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin read descriptions of Pelican Bay’s SHU as an example of the extreme inhumanity of solitary confinement.

So, what next? “So it’s now all about ramping up support for a new round of peaceful responsive actions,” wrote Ashker in a recent letter. [Asher, June, 10, 2012.]

Supporters are doing just that: To commemorate the strike’s one-year anniversary, Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity, a Bay Area coalition of family, friends and supporters of the hunger strikers, will be organizing a Month of Education, including building a replica of a SHU cell to be used at outreach events, organizing educational events (and urging those in other states to do the same), continuing legal visits and setting up a pen pal network to connect California prisoners with outside supporters.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.