Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

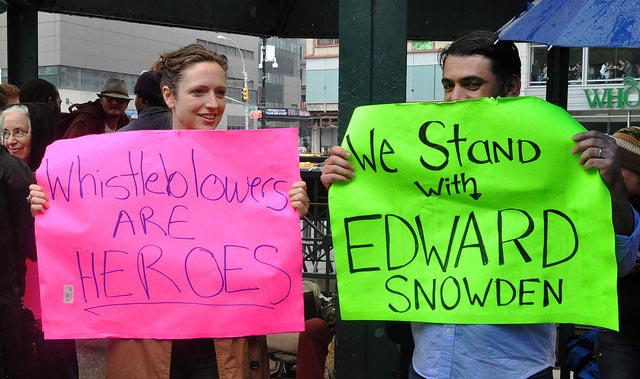

In the ramped-up secrecy of post-9/11 America, many of the more controversial revelations about U.S. national security and intelligence agencies have come to light via whistleblowers: conscientious objectors within government agencies.

While Edward Snowden may be the most recognizable name, many others have also come forward to raise awareness about secret programs ranging from CIA torture at so-called black sites to recent revelations to The Intercept about kill list assassinations by drone strikes.

FSRN’s Shannon Young brings us this first installment of a series on the intersection between technology, surveillance and democracy.

When whistleblowers come forward publicly, many say they’re motivated by the conviction that the American public has a right to know what goes on in the shadows of their government.

But agencies and the White House have been striking back. The Obama Administration has prosecuted more whistleblowers under the 1917 Espionage Act than all other presidents combined. And in October of 2011, after Chelsea Manning handed over a huge trove of diplomatic cables to Wikileaks, President Obama issued an executive order creating the so-called “Insider Threat Program” to mitigate future leaks of classified information.

Mike German is a former FBI agent and whistleblower who, more than a decade ago, brought up concerns about structural failures within the bureau’s counter-terrorism division. He says the main aim of the Insider Threat Program is to suppress dissent within intelligence organizations and any media reports about its causes.

“Basically what it is was doing was creating more strict rules on anybody from the intelligence community talking with the media,” explains German. “And creating and authorizing managers within the intelligence community to have greater surveillance of their employees.”

The Insider Threat program was in place during Edward Snowden’s time as an NSA contractor. During a keynote delivered via video stream last week to the Computers Freedom and Privacy conference, Snowden says he’s heard the program itself has ramped up even more since he came forward.

“They’re actually saying ‘don’t respond to reporters, don’t talk to the press, close yourself off, don’t get involved with that at all, refer people to public affairs officers because they’re the only ones, and then report the journalists to security,'” Snowden told the conference. “‘If you hear a co-worker that you think has any involvement with any sort of reform organization or a journalism organization, those can be indicators of hostile intent.’ And these are sort of red flags that you’re supposed to self-report to security. I think that sort of radically changes the dynamic of who’s in charge of these institutions, of these agencies, of these organizations. Because ultimately it should be the public holding the leash. But the public understands the nature of its government through its press.”

Going to the press has long been a favored option for many whistleblowers who have either given up on, or never trusted, the internal systems for raising concerns. But reporting on leaked information can be a risk many media outlets, including large outfits with legal departments, are unwilling to take.

Other whistleblowers have taken their concerns to members of Congress, but that process can also be tricky. “The system as it’s built right now, it’s questionable – the way the government would interpret it – it’s questionable whether even going to your member of Congress, unless that person is actually on the Intelligence Committee, would be protected,” explains Mike German. He says Congress is at least partially to blame because it hasn’t adequately protected its own ability to get information, even when it had a chance to pass meaningful reform in 2012.

“When the Whistleblower Protection Act was being enhanced, the original House version included strong protections for intelligence community employees, but those were taken out in the Senate and ultimately nothing was passed,” notes German. “It was watered down in the Senate and ultimately nothing was passed that would’ve actually protected their right, clearly, to get information from government employees. And that’s a real part of the problem. They have to realize that the flow of information through official channels is not the only one they need, that they need access to dissenters within the agencies as well.”

It was Congress that passed the legal framework for the mass surveillance programs that Edward Snowden revealed. Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act were two key provisions.

“You know, there are some in Congress who want to give our national security agencies a blank check. They think any attempt to protect our privacy somehow makes us less safe,” said Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont, speaking Wednesday at a conference on surveillance and privacy hosted by the Cato Institute. He said while coalition building to enact reforms can be complicated, it is possible, especially with public pressure. He pointed to how Congress voted against renewing Section 215 when it sunset earlier this year. Leahy noted that the FISA Amendments Act (which include Section 702) sunsets in 2017.

“Protecting our basic rights and protecting the country are not part of a zero sum equation. We can do both. But we have to keep in mind if we don’t protect America’s privacy and constitutional liberties, what have we given up? Frankly, I think far too much,” Leahy remarked.

Whistleblower Mike German argues that accountability is a key component of an effective security strategy, but that most Americans have become inured to the idea that a part of the government operates in secret with free rein and no oversight.

For his part, Snowden says an informed and engaged citizenry is crucial to push for change.

“Whistleblowers are valuable, but they can do nothing in a vacuum. It requires a civil society. It requires a free press. It requires reporting and -eventually collective congressional action, institutional action. Also through the courts is a good way to force reform,” explains Snowden. “Because that pendulum will always swing too far and one of the reasons that I felt so compelled to come forward when I did is not because I felt that the pendulum was irrecoverably far but because I saw it moving in a direction. And I feel that citizens, individuals have an ability, particularly when they’re inside and witness these programs that are occurring without our knowledge or consent, to arrest that swing.”

As the pendulum continues to swing along its arc, those people most intimately aware of the forces at play face the tough choice between infamously ineffective internal complaint mechanisms and the risks of going to the press: facing criminal charges and being labeled a traitor.

Whistleblowers will likely remain stuck between that rock and a hard place unless significant public pressure is able to rally lawmakers to enact reform.

Edward Snowden and Mike German: A Conversation Between Two Whistleblowers

{mp3remote}https://fsrn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/EdSnowden_MikeGerman.mp3{/mp3remote}

During the coming weeks, FSRN will feature a series of reports on the intersections of technology policy, digital privacy, press freedom and democracy. As a preview, we’re publishing the entirety of a extended Q&A session between two whistleblowers – former NSA contractor Edward Snowden and ex-FBI agent Mike German.

Hillary Clinton recently criticized Snowden’s whistleblowing, saying that he should have come forward with his concerns through internal procedures. In his time at the FBI, Mike German did just that and shared his experiences and reflections in this 60 minute interview with Snowden.

The conversation, held live at the opening session of the 25th annual Computers, Freedom and Privacy conference, ranges from how 9/11 created a generation gap at the country’s intelligence agencies, how internal programs at this agency suppress dissent within the ranks, and why an adversarial press is crucial to a healthy democracy.

Mike German: It’s interesting that there’s so much similarity in our backgrounds. We both come from a military family, both spent a lot of time in the DC area growing up, both went into federal service. As that’s what you do, right? You go into the government and go to work. And really I think the big distinction is that you came into the intelligence community, into the military, after 9/11. Where I came in in 1988 when the lessons from the previous intelligence scandals – and particularly the framework for the reforms – was very present in everyone’s mind. And what I saw was a big transition after 9/11 that – well, I’ll let you explain whether that was actually something that was in the front of people’s minds when you started at these agencies.

Edward Snowden: I definitely think so. I mean, when I first entered into government service, I was enlisting for the Army in 2004 when everyone else was protesting against it because when you grow up in the shadow of government, you don’t really doubt it. Like you said, it’s what you do; you grow up, you work for the government and eventually retire.

But in 2005, I started working for the CIA as a contractor. And that was quite unusual because, although I had a significant amount of technical skill, I didn’t have a lot in terms of paper credentials. I had some industry certifications and things like that, but the Bush administration had really gone on a hiring tear for all of the intelligence community, but specifically for the CIA, the NSA, groups like that. And so when I joined, there was this incredible bifurcation in the workforce where you had sort of a group of old-timers who grew up going through training learning Morse code and how to solder, you know, radios together. They didn’t think that when something breaks you just threw it away and got another one like you do today. They basically had to field service everything.

And then you had this new generation where everything was digitized, everything was computerized. What made us valuable was the fact that we had mastered a new sort of era of technology. But what we all lacked was the institutional history of why the reforms happened and why they were so necessary. We still knew about them in sort of a generalized academic sense because every year in government you’ve got these sort of annual training requirements where you’ve got to tick the box saying you watched the flash presentation or read the fifteen-page whatever. And we got those, but it wasn’t really something from our generation, it was considered solved problems, secret history. And rather than, bearing in mind that power and reach and extension by government can be dangerous, not just to our adversaries but also inside, to our own civil society.

We were in this new moment, where anything could be justified. I mean, whether it was torture or mass surveillance, targeted killings, and so on and so forth. The motto the I learned, almost the first day when I came in, and this was as a contractor before I was even sworn in officially as a CIA officer, was “mission first.” Mission first. That’s really all that mattered. Not when do we go home, not what you do, but the mission. The mission was all that matters. And I think that did have a lasting impact on not just this new wave, but it gave an organization a chance to change its character and its culture radically, and I think that’s happened because the majority of those holdovers have since retired.

(This is only a partial transcript of the 60 minute audio)

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.