Part of the Series

Movement Memos

The Road to Abolition

Why would police want a multimillion-dollar gunshot detection system that doesn’t work? “ShotSpotter manufactures the urgency of an active threat, offering situations where there is likely no risk, but where police can operate within a narrative of extreme risk,” says Kelly Hayes. In this episode of “Movement Memos,” Kelly talks with Chicago organizers who are attempting to rid their city of an acoustic surveillance system that is both ineffective and dangerous.

Music by Son Monarcas and Viriya

TRANSCRIPT

Note: This a rush transcript and has been lightly edited for clarity. Copy may not be in its final form.

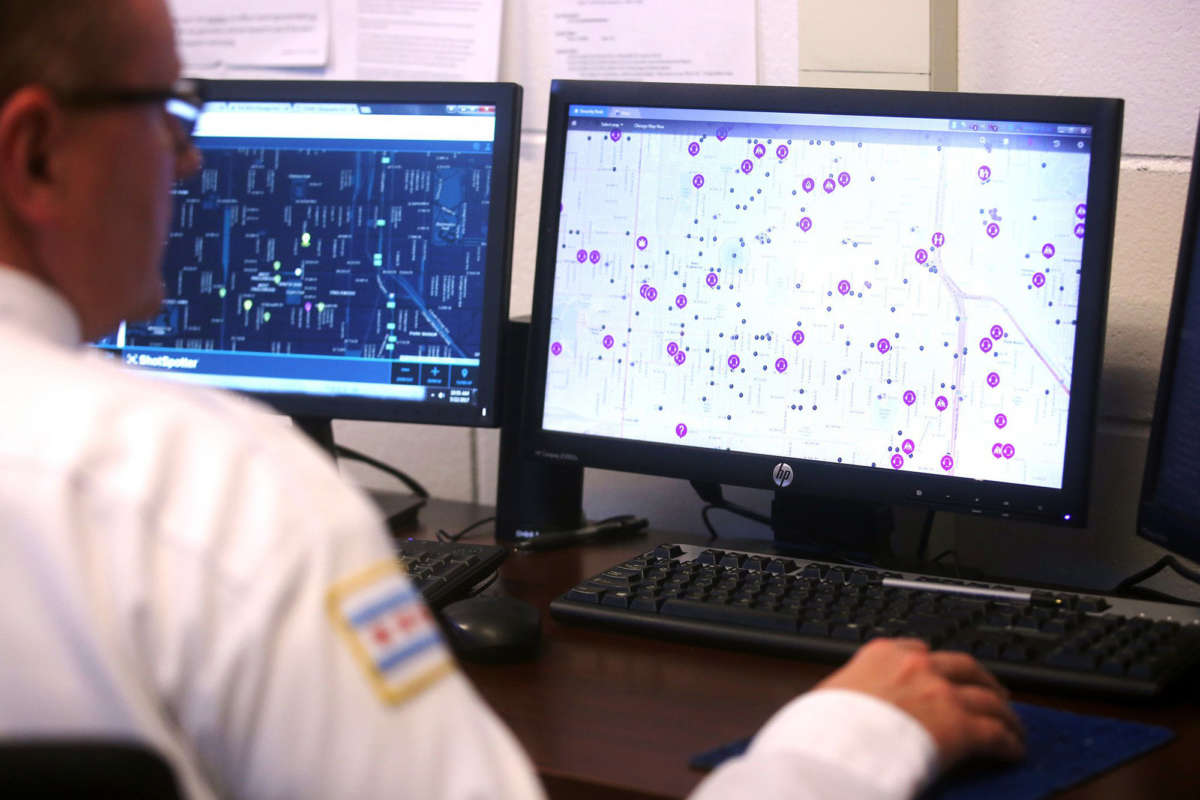

Kelly Hayes: Welcome to “Movement Memos,” a Truthout podcast about things you should know if you want to change the world. I’m your host, writer and organizer, Kelly Hayes. We talk a lot on this show about building the relationships and analysis we need to create movements that can win. Today, we are talking about the surveillance state, and how a coalition of activists in Chicago is seeking to interrupt its work. The surveillance technology known as ShotSpotter sounds like something out of a modern dystopian novel: a sea of microphones, scattered across oppressed communities, supposedly to detect gunshots, for the purpose of community safety. But in reality, the technology rarely turns up actual gun-related crime, and instead leads to harassment, brutalization, false imprisonment, and death for targeted community members. Despite these harmful outcomes, police tout the need for the technology, which costs about $95,000 per square mile per year, and claim that it is integral to their work. The company itself argues that the use of its tech should be expanded, and that schools should also be blanketed with microphones, as a form of early detection for school shootings. So today, we are going to talk about Chicago’s Stop ShotSpotter campaign, and why some police departments are determined to keep a multi-million dollar surveillance system that is both ineffective and dangerous.

In 2018, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) signed a three year, $33 million contract with Shotspotter, with the option for renewal in August 2021. The ShotSpotter system now covers 117 square miles across 12 police districts, mostly on the city’s South and West sides, making Chicago one of the company’s best customers. The company has contracts in over 100 U.S. cities.

In Chicago, the technology’s deployment was largely paid for with funds acquired through the war on drugs via civil asset forfeiture — a controversial process that allows police and prosecutors to seize cash, vehicles, or other goods if they believe those resources are tied to a crime. Chicago police have previously faced criticism for using civil forfeiture to maintain a secret budget that critics say functions “outside the bounds of normal accountability.” A 2016 investigation in The Chicago Reader found that CPD used civil forfeiture funds to pay for some of its day to day narcotics unit operations and “to secretly purchase controversial surveillance equipment without public scrutiny or City Council oversight.”

In the spring of 2021, 13 year-old Adam Toledo was gunned down by a police officer in Chicago’s Little Village Neighborhood. Body cam footage subsequently revealed that Adam had his hands in the air when he was shot. There were, predictably, no charges filed against the officer who shot Adam, but some community members zeroed in on the question of how that police officer wound up chasing Adam that night. CPD’s ShotSpotter surveillance system had issued an alert indicating that a gun had been fired in the area, which led to officers being deployed. In the wake of Adam’s murder, some Chicago organizers began to converge around the goal of eliminating ShotSpotter’s contract with the city.

One of those organizers was my friend, Freddy Martinez, who is a cofounder of Lucy Parsons Labs in Chicago and a co-author of that investigative report about civil asset forfeiture. Lucy Parsons Labs is a collaboration between data scientists, transparency activists, artists, and others who take an abolitionist approach to research, technology and digital rights. LPL is also a major resource to organizers and journalists in the city of Chicago when it comes to understanding the scope of the surveillance Chicagoans face. Most people have never heard of ShotSpotter, or the context in which these systems are being deployed, so I asked Freddy if he could offer us some background.

Freddy Martinez: So what is ShotSpotter? So it’s an array of essentially microphones and using acoustic sensing and different physics techniques, they’re supposed to say that, “We detected this gunshot.” And then what happens is when the microphones pick up an alert, they send it to an analyst, some person who’s sitting in some customer support office who then would listen to the sound, and then pushes a notification out to people on the ground, police officers, who then respond thinking that there is a armed person, a quite potentially dangerous situation. And so, that’s kind of how the system looks overall.

The problem with ShotSpotter is that there has never been any kind of evidence, any research that it actually functions in large cities. So, how do you differentiate between gunshots and car backfiring or fireworks? In fact, they don’t. They just turn it off on the 4th of July. So that’s the first part.

The second part is that we really have no idea where there are errors in some of these processes right there. There’s obviously human error, there’s error in the detection algorithms that the company has written. And then, there’s this idea of, what happens after the alert goes out, right? And so, you have cops that are responding to these alerts dozens of times a day, and we basically have no evidence of what happens after these alerts go out.

The reason for that is that ShotSpotter claims that it’s something like 97% accurate. And the way that they get to that number is quite clever. What they do is that they classify basically every sound that they pick up as either one, a gunshot, a single gunshot, multiple gunshots, or what they designate as a probable gunshot. And that’s included in their accuracy number. I studied science, accuracy means a very specific thing, it doesn’t mean, it’s probably a gunshot, so put it down as it is a gunshot and send cops out to the field.

The company claims, well, don’t you want people — you know, someone dials into 911 and they think that they heard a gunshot but they’re not sure, shouldn’t police respond anyway? It’s like, well yes, that’s true but then what actually happens on a deployment is nothing. The cops show up and they find absolutely nothing. And this happens dozens of times a day, but it also brings really dangerous interactions with the public.

Chicago is often one of the incubators of surveillance technology. It’s often one of the first adopters. They love to go to police tech conferences and say, “Here’s what we’re trying out, and here are all the things that we’re doing.”

The CPD has experimented with all sorts of algorithms that claim that they can predict who, what, where, when crime will happen. They were early adopters into what then called the CAPS Program, but eventually they started calling community policing all over the country, where the premise is just basically have cops talking to people, more interactions with the people everywhere.

And I think this misses a lot of the — when talk about police tactics nationally. I think a lot of people don’t see Chicago as a major player. People always talk about LAPD, people always talk about NYPD, but really Chicago is one of these incubators for experimenting on the public.

KH: So, as Freddy explained, ShotSpotter claims that its product is 97% accurate, and supporters of the technology, including police departments that want to keep the tech, are quite prone to uplifting that number. But when I looked at any report that wasn’t compiled by the ShotSpotter marketing department, I came across very different numbers. According to a report from The MacArthur Justice Center at Northwestern University School of Law, for example, 89% of ShotSpotter deployments in Chicago turned up no gun-related crime. 86% led to no report of any crime at all. The report indicated that over the 21.5 months researchers studied, there were more than 40,000 dead-end ShotSpotter deployments in Chicago. On an average day in Chicago, the report found, “there are more than 61 ShotSpotter-initiated police deployments that turn up no evidence of any crime, let alone gun crime.” That study was conducted between July 1, 2019 and April 14, 2021.

In August, Chicago’s Office of Inspector General’s Public Safety section reported that the police department data it examined “does not support a conclusion that ShotSpotter is an effective tool in developing evidence of gun-related crime.” The report indicated that between January 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, about 50,000 “probably gunshot” alerts were issued by ShotSpotter in Chicago, each of which resulted in Chicago Police being deployed. The report found that, out of all those deployments, a total of 4,556 incidents in which “evidence of a gun-related criminal offense was found.” That represents 9.1% of CPD responses to ShotSpotter alerts.

But when we talk about what we know about ShotSpotter in Chicago, and how organizers have been able to seize upon this issue, we should highlight the fact that activist researchers have been sizing up the surveillance state in Chicago for years, including ShotSpotter, using the Freedom of Information Act, in addition to other methods. Lucy Parsons Labs has gained quite a reputation in Chicago for its in-depth research and dogged cataloging of details that politicians would rather keep buried.

When Adam Toledo was killed, organizers like Freddy were able to offer immediate assistance to people who wanted to understand the surveillance system that set Adam’s fatal police encounter in motion.

FM: So we, for a long time have just been documenting and cataloging police use of surveillance technologies. We’ve done a lot of deep research, we did a lot of lawsuits, to uncover that information. And so, what that allowed us to do is be one of the people that could just plug in immediately. And when people were having questions about, what is this technology? How does it work? What are the pitfalls? What are the police saying, but what’s the actual truth on the ground, and how does it fit into these larger narratives of like anti-Blackness or histories of repression?

We became one of the groups that could answer those questions immediately. I remember at one point there was a journalist on Twitter who had said that weekend that Adam Toledo got murdered was like, “I think I’m going to spend this weekend looking into everything I can about ShotSpotter.” And I said, “Hey, don’t worry about it. Go to our website, chicagopolicesurveillance.com. It’s all on there.” And having those resources ready to go is really critical for just organizing work. And that’s kind of been what we’ve sort of focused on for the last couple of years.

KH: I also spoke with Alyx Goodwin, an organizer with Chicago’s local Defund CPD campaign and the deputy campaign director for the Action Center on Race and the Economy. When we spoke, Alyx told me she’s committed to eliminating the ShotSpotter contract, not simply because the product is ineffective, but also because it’s part of a racialized and deadly system of surveillance that brings violence upon Black and brown people.

Alyx Goodwin: Surveillance is actually the way I started to really get a grasp on racial capitalism. Growing up, I understood Black people to be surveilled in a specific way, right? I knew about COINTELPRO, I knew about the dismantling of the Black Panther Party and other organizations. I know Black communities are over-policed, that was my entry point to understanding policing and surveillance as a Black person. And then I met with folks who are undocumented, and experiencing surveillance through ICE and immigration, and the way federal agencies are surveilling folks. And then I met with folks who are Muslim, Arab, South Asian, who are surveilled in a specific way, with a different set of programs and at the end of the day, it is all surveillance. It is all for the purpose of maintaining the status quo, and that was just a huge light bulb for me. Even this ShotSpotter campaign — we’re trying to understand the way ShotSpotter is informing surveillance, other forms of surveillance, other surveillance tools.

So we know that ShotSpotter, per the OIG report, we know that ShotSpotter has also changed police behavior, basically increasing stop and frisk. And we also know on the other side with the gang database campaign, that cops are performing these, what they call “investigatory stops” on people who they believe are gang members. So, there is very likely a strong correlation between ShotSpotter alerts in specific neighborhoods informing the number of stop and frisk, and the way stop and frisk is happening to folks who are now being stopped and labeled as gang members.

I think it’s also important to name that in the OIG report, it’s described as the narrative that ShotSpotter creates about a neighborhood, is what is encouraging officers to stop and frisk folks. So, they’re already going into this with the frame of mind that this is a dangerous neighborhood, or there’s gang members here, whatever excuse they are using to justify. And so, I think I want us to really hammer down folks who are listening, and coming into the ShotSpotter campaign, to understand that this is a piece of a larger puzzle. Not to overwhelm folks, but if we tear down this particular piece of surveillance, what other wins is that going to open us up to? I think it opens us up a lot to winning a lot of other things, and to breaking down other parts of the police state.

One of the things that the campaign talks about is that ShotSpotter is not actually a public safety solution, for a number of reasons, one of them being it’s sending police in and making situations worse and more violent. ACRE, my day job, did a report called “21st Century Policing: The Rise and Reach of Surveillance and Police Technology.” And in that report, we had a chance to highlight ShotSpotter, and that came out earlier this year. And then I want to say around the same time in Chicago, was the very untimely death of Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old, who lived in Little Village who was killed by the Chicago Police Department because a ShotSpotter alert took them to his location.

And we talk a lot about justice for families, and justice for people who are in communities who have been impacted by police violence. And it just kind of felt like, in that moment, we had no choice except to work to cancel the contract. Because as a mom of two myself, I cannot fathom, it’s really hard, just the sheer amount of anger that I feel for Adam’s mom. I can only imagine how she feels, and how other families feel, how other communities feel when they’ve lost somebody to police violence, when these are things that could have been avoided if we were not investing money in policing, and if we were not investing money in surveillance, but instead investing that money into things that communities are asking for and demanding. For some reason it is so difficult for them to find money for housing and mental health, but it is not hard for them to find money for police. And that is also, I think, one of the issues that we want to raise with this campaign.

KH: According to The Associated Press, ShotSpotter evidence has now been admitted in over 200 court cases around the country. Reports prepared by ShotSpotter staff have also been used in court to make dubious assertions about whether defendants fired at police, or how many shots were fired during a particular incident. The AP’s investigation also found that “the system can miss live gunfire right under its microphones, or misclassify the sounds of fireworks or cars backfiring as gunshots.”

65-year-old Michael Williams spent nearly a year in Chicago’s Cook County Jail, facing a murder charge on the basis of evidence mined from ShotSpotter. A silent clip of security footage showing a car driving through an intersection, and a noise picked up by ShotSpotter’s sea of microphones were the only evidence against Williams, who eventually considered taking his own life to escape the torment of incarceration. Prosecutors, who initially claimed ShotSpotter’s secret algorithm had cracked the case, eventually asked a judge to dismiss the charges against Williams, citing insufficient evidence.

The ShotSpotter contract was discussed at a recent meeting of the Chicago City Council, and activists I spoke with had strong feelings about the arguments police and ShotSpotter representatives made in defense of keeping the contract.

AG: One of the police officers, I don’t remember his title, his last name is Snelling. And he was saying like, “Yeah, we talk about the 90% number, ShotSpotter not being effective 90% of the time, but we need to focus on the 10% of the time when it is effective.” And that it just sounds like, 10% is an F, that is technically an F, that is basically a zero. And I could not imagine ever trying to come home with 10% and being like, “Look, just focus on the fact that I wrote my name on the paper.” Right? I think that they were trying really, really hard in the hearing to make a case for needing ShotSpotter without having any data to actually back up why they would need ShotSpotter. Which was really, it was exciting to watch because it felt like we had caught them up in the marketing that is ShotSpotter. Like, the numbers, this is all marketing for a product. It’s not like an actual public safety investment, despite what they want us to believe.

And so, yeah, I think that part of why CPD is so invested in keeping ShotSpotter is just because that further legitimizes their role as an institution for violence and harassment, to be the public safety solution.

FM: ShotSpotter people actually said at the hearing, they’re like, “We are relying on data. Data is neutral. Data is objective. We’re only going off of data.” And literally all of us just starting pulling our hair because anyone that studies crime and sociology, knows that data is not neutral. But that’s who our opponents are. They’ll say anything as a way of obfuscating what they’re really doing. They’ll say these things that everyone who’s acting in good faith would never claim. I would never claim that data on crime is neutral in any way.

One of the things that they kept saying over and over at the hearing was, what about the one time that someone was responding to a ShotSpotter alert and they find someone that’s injured? That’s why this technology works. That’s not a good way of making public policy.

I have to make the joke that at one time I was able to buy Christmas presents because I picked up $400 that someone had dropped outside of the Target, but that’s not how bills get paid, right? And so, when we were talking about the difference here about what true public safety looks like and investing money into mental health and violence interruption programs instead of ShotSpotter precisely because we see that there’s this marketing talk of 97% accuracy.

And then what happens, when CPD responds 96% or 91% of the time, they don’t even write a report. They don’t even open any kind of investigation. There’s no shell casings. There’s nothing for them to do. And then what does happen though, is that we know for a fact that they will write reports about, we found someone with weed on scene or someone with an open container.

We have to figure out how to shape this narrative in a way that’s both talking about what the actual facts on the ground are but also rooting out actual factual answers from an abolitionist perspective, because we know that just dumping more money into the police will not keep us safe. Forget ShotSpotter itself not working properly, even if it did, we still wouldn’t want that money that should go to violence prevention programs going into technologies just because they’re good at marketing.

KH: Organizers with the Stop ShotSpotter campaign say that the city needs to address the root causes of harm and violence in Chicago’s communities, but they understand why that argument is a hard sell with neoliberal city officials.

AG: Abolition is not profitable, and Chicago is a business relationship for ShotSpotter, Chicago is the second biggest contract. And were the city to invest in things that the community identifies as true public safety, ShotSpotter wouldn’t make money. It would probably lead us to finally reckoning with the fact that we need to lay off police officers. Once we start recognizing that a lot of this is profit-driven, and moving on the fact that a lot of policing is profit-driven, the institution would fall apart.

I also think that it’s important to name too, that as calls for abolition and defund have gotten louder, the reform industry is booming. Because again, were we to move towards abolition, there’s a number of industries that would fall because of that. So I also think that this is also about business relationships.

KH: Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot often portrays abolitionists and other critics of police as out of touch and insensitive to the plight of neighborhoods that are besieged by crime and violence. It is, in fact, a common criticism of prison and police abolitionists, and of the movement to defund the police, that demanding disinvestment from the police is a privileged, white perspective. But most abolitionists are not white, and the ideas that propel this work were incubated by Black and brown people who were subject to the very violence they were critiquing. This remains true of most abolitionist organizing today, including the Stop ShotSpotter campaign.

FM: When I think about the campaign and the people that are involved in it, I think one thing that I really appreciate and like about it is just how representative we are of the actual people who are facing these issues and have to tackle them and offer actual solutions that we know will keep us safe, that will lead to collective safety. The mayor likes to say that us abolitionists don’t care about victims of crime and things like that.

And when I saw the murder of Adam Toledo, he was killed outside of the high school that my cousins went to. I know that neighborhood. I’m from that neighborhood. I grew up in that neighborhood. And in a lot of ways, I think that coming to this campaign is a way of both trying to do something for me personally going back 20 years or 25 years and wishing I had lived in a neighborhood that was safer, but also realizing that the solutions are going to come from people like me and from people like Alyx and all of us because I mean, we have to be involved because ultimately, we keep us safe, as they say. That’s one thing that’s been sticking with me a lot, thinking about the campaign and some of the work we’ve been doing across the city.

KH: Amid public debate about the contract’s renewal in August, activists and members of the Chicago City Council learned that the city’s ShotSpotter contract had been quietly renewed back in December. Some members of the City Council objected to the administration’s lack of transparency, with one alderman calling the renewal “an abuse of authority.” While City Council members talk about how to prevent similar incidents in the future, organizers with the Stop ShotSpotter campaign are reminding the public that the contract is still vulnerable.

AG: So, the contract can be canceled at any time. There’s no legal penalty, there’s no fines. If City Council does not appropriate the money, the contract is canceled. And so for folks in Chicago, we need folks telling their city council member, by calling them, or emailing them, or tweeting at them, Alderwoman Pat Dowell does not like to be tweeted at, so I would highly suggest you tweet at her. But we’re letting them know that folks, we don’t want ShotSpotter in our wards. We don’t want the city paying nine million dollars for this technology, we want nine million dollars invested in structural solutions, in community-led violence interruption and prevention, like the Peace Book, for example. That’s one thing.

We’re also collecting petition signatures, tonight we hit over 2,500 signatures, which is really exciting. Because [the] City Council is saying, “We need to see the data,” so we showed them the data that ShotSpotter doesn’t work. And they said, “Oh, well, we need to hear from our constituents,” so we are showing them that their constituents that don’t want ShotSpotter exist, and are here and are loud.

And so, really the most important thing that folks can do that are in Chicago, is tell their Alderperson that they don’t want ShotSpotter used in their ward, or anywhere in the city. For folks who are not in Chicago, if ShotSpotter has a pilot in your city, hit us up, hit folks up in Chicago, because we are looking to support other local campaigns that want to cancel ShotSpotter contracts, or make sure that ShotSpotter doesn’t happen in their city. Also, I would also highly suggest tweeting at Ralph Clark, who is the CEO of ShotSpotter. This man makes a million dollars a year, he lives in the Hills of Oakland very comfortably, and is profiting off of the harassment and surveillance, and gun violence of Black people and Latinx people in Chicago and around the country. And that is just not right, on so many levels.

KH: Given that police casually inflict violence upon marginalized people, robbing people of life, liberty and dignity, there’s something especially draconian about technology that summons such forces to a targeted community anytime there’s a loud noise. In Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision, Brendan McQuade wrote that the basic mandate of police power is to “regulate poverty and fabricate capitalist forms of order.” According to McQuade, mass surveillance projects and the work of “security” are not a response to disorder, but rather, “the political work of managing poverty and pacifying class struggle.”

Police do not function as community members, operating in the pursuit of communal safety. They operate in opposition to communities targeted for criminalization and pacification. ShotSpotter offers opportunities for instigation wherein community members are assumed combatants. The social impunity that police enjoy often rests on the idea that police have to make split second decisions in life threatening situations. ShotSpotter manufactures the urgency of an active threat, offering situations where there is likely no risk, but where police can operate within a narrative of extreme risk. In this way, ShotSpotter serves up an ideal narrative context for police deployments — one that cloaks the everyday violence of policing in ShotSpotter’s algorithmic fog of war.

A few years ago, a couple of friends of mine were sitting outside on a summer day, outside one of their homes, when the police rolled up. The officers who approached them claimed there had been gunfire in the area and demanded to know what my two friends had seen and heard. My friends, a Latinx woman and a trans white woman, told the police they had not seen or heard anything and did not believe there had been a gunshot. The police insisted that they were certain there had been a gunshot because the ShotSpotter system told them so, and they accused my friends of covering for gang members. The police demanded to know why my friends would protect violent criminals who, as far as we know, did not exist. Two marginalized people were at risk of experiencing violence, or arrest, that day, in an accusatory confrontation with police, generated by a faulty algorithm. My friends managed to back away from the situation safely, but the more often incidents like this occur, the more often they will result in abuse, dehumanization, the indignity of arrest, or even the death of a marginalized person.

Adam Toledo’s case gained attention because body camera footage revealed he had his hands up at the moment he was killed. Such moments of exposure are rare for police, who generally enjoy the white-washed image that cop shows and doting politicians have upheld for generations. In Adam’s case, we saw a convergence of surveillance devices that we are told exist to protect the public: police body cameras and ShotSpotter. A ShotSpotter alert summoned the police. A police officer’s body camera documented that Adam’s hands were in the air when a police officer killed him. And in the end, that footage meant nothing, because the surveillance technology that captured it does not exist to protect people like Adam, and neither do the police.

We live in a time when biometric surveillance systems, facial recognition software, e-carceration and ubiquitous cameras have created new avenues for policing and social control. We know that these technologies are often faulty, and that even when they work, they are empowering an inherently violent, racist system — one where police freely harass, brutalize, cage and kill with impunity. In Chicago, we are witnessing a vicious cycle, where funds captured in the war on drugs fund narcotics unit operations and controversial surveillance devices, including miles of microphones. And those listening devices, working in concert, provide cover for more aggressive police deployments.

But cycles can be broken and organizers are fighting to end ShotSpotter contracts, to ban facial recognition software, and to shut down surveillance technologies that are being deployed against migrants and other criminalized people. San Antonio, Charlotte, and Fall River have all ended their ShotSpotter contracts, deeming the technology costly and ineffective. Seven states and nearly two dozen cities have limited government use of facial recognition technology. Groups like Mijente are organizing for a surveillance free future and targeting tech companies that provide ICE with its predatory infrastructure. The Illinois Coalition to End Money Bond is pushing “to reduce the harm done by pretrial electronic monitoring and to eliminate its use in the long run.” We have so much to dismantle, and so much yet to build, but we can always begin by learning, and by sharing what we know, and then shaping narratives that can help others understand that a dystopian sea of microphones is not what public safety looks like. Safety comes from people working together to change the material conditions that generate harm and despair, and I hope we are ready to do that work together.

I want to thank Freddy and Alyx for talking with me about Stop ShotSpotter, security and abolition. I learned a lot and I really appreciate the work they’re doing. I also want to thank our listeners for joining us today, and remember, our best defense against cynicism is to do good and to remember that the good we do matters. Until next time, I’ll see you in the streets.

Show Notes

Take Action:

- You can sign the petition to cancel ShotSpotter and support community-led solutions to address gun violence in Chicago here.

- From the StopShotSpotter organizers: “This toolkit contains background information, resources, and calls to action for you to learn more about this campaign and support the Coalition’s goal to not only get rid of this tech, but to also reinvest those funds into the things that would actually create safety in our communities, like the Peace Book and Community Restoration Ordinance.”

Further Reading:

- Chicago watchdog harshly criticizes ShotSpotter system by Don Babwin and Garance Burke

- How AI Powered Tech Landed a Man in Jail with Scant Evidence by Garance Burke, Martha Mendoza, Juliet Linderman and Michael Tarm

- ShotSpotter creates thousands of dead-end police deployments that find no evidence of actual gunfire (MacArthur Justice Center)

- Chicago Inspector General: Using ShotSpotter Does Not Justify Crime Fighting Utility

- Summary of OIG Report report

- Community groups demand city oust ShotSpotter gunshot detection system by Patrick Elwood

- Chicago Should Cancel ShotSpotter Contract After Report Shows Police Influence On Technology, Activists Say by Mauricio Peña and Justin Laurence

- Op-Ed: End the City’s ShotSpotter Contract by Freddy Martinez and Lucy Parsons Labs

- Chicago Awaits Video of Police Killing 13 Year-Old Boy by Jamie Kalven

- The Shots Heard Round the City by Michael Wasney

- Critics see waste, bias in Chicago’s multimillion-dollar gunfire-detection system by Emily Zantow

- Inside the Chicago Police Department’s secret budget by Joel Handley, Jennifer Helsby and Freddy Martinez

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $44,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.