Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

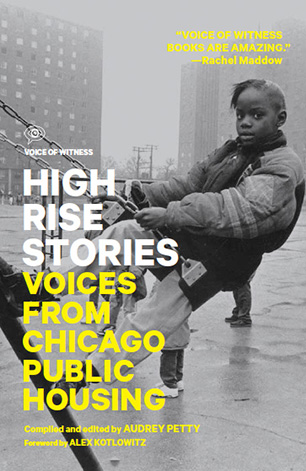

High Rise Stories: Voices from Chicago Public Housing, compiled and edited by Audrey Petty, foreword by Alex Kotlowitz, Voices of Witness Project, McSweeney’s Books, 2013, $16, 280 pages.

Despite its title, High Rise Stories is about far more than public housing in one US metropolis. It’s about failed public policy, heartless bureaucrats and, perhaps most importantly, it’s about people at the bottom of the economic heap, people whose lives are further marred by alcohol and drug abuse, educational neglect, mental and physical illness, gang violence and domestic abuse, among other maladies. At the same time, it’s a gripping account of people trying their hardest to make ends meet and keep themselves and their families out of harm’s way.

Indeed, High Rise Stories will make you simultaneously want to groan in despair and cheer from the rafters. Here’s why.

In 12 wide-ranging oral histories, editor Audrey Petty allows former and current residents of Chicago public housing to talk about their lives. There are old people, young people, former gang bangers and teenage moms. The backdrop – a common denominator of sorts – is the projects, the buildings that began going up in 1937 after Congress passed the Wagner-Steagall Act and provided money to dozens of cities across the country to build decent, affordable homes for those who lacked the resources to pay market rates. At its peak, the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) managed 43,000 units and sheltered approximately 200,000 people. Sixty years later, in 1998, Petty writes, “nearly 19,000 CHA units failed viability inspections mandated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, meaning that under federal law, the authority was required to demolish those units within five years.”

So down they went.

Lip service to resurrection – a $1.6 billion project called the Plan for Transformation – promised displaced residents government-sponsored replacement housing in mixed-income developments. But, predictably, building has fallen far short of stated goals. Alex Kotlowitz, in the book’s foreword, succinctly sums up the demolition’s aftermath: “Now that the high rises are gone, former residents still struggle to attain the American ideal, a place where education would afford opportunities for their children, a place where they could live in safety and security, a place where if they worked hard, success would follow.” Instead, he continues, former CHA residents “have been scattered to the winds, many living in equally impoverished neighborhoods in the city.”

That CHA buildings were so deteriorated that they needed to be razed rather than renovated is a shocking illustration of the not-so-benign neglect that plagues poor communities. Some, like the Henry Horner Homes, were just 36 years old when they were destroyed. High Rise Stories tells the heartbreaking story of CHA mismanagement by making the political personal and casting a clear eye on the human toll of institutional racism and classism.

Among those testifying is 83-year-old Dolores Wilson – who now lives in Dearborn Homes, one of the CHA’s few remaining complexes. She moved there after being forced out of the Cabrini-Green Houses in 2011. “I loved that [Cabrini-Green] apartment,” she begins. “The apartment had three bedrooms and was on the 14th floor. When I first stepped off the elevators in 1958 and looked out over the railing I thought I was going to faint! I’d never been that high.” Wilson worked for the City Water Department, and her husband, Hubert, was a janitor. Both were active in the neighborhood. Hubert ran a drum and bugle corps for local kids, and she served on the building council. In the early days, she continues, people watched out for one another, and the city did its best to make repairs and maintain the buildings. But things changed in the 1980s. “The older kids – the boys – they didn’t join gangs because they wanted to, but with other gangs moving into the neighborhood, this made them form gangs in response, for self-protection. … Even I wanted to carry a gun.”

Wilson’s son Michael was one of the casualties of the burgeoning violence, killed by a random bullet while standing in front of his church. Wilson reports that police response to the shooting was lackadaisical, as if they could not be bothered to investigate the murder of one more black man. On top of this, Wilson notes that increasing violence was not the only change unfolding at Cabrini-Green. As gang activity escalated, building maintenance began to decline, she says. Elevators took longer to be repaired, hallways were cleaned less frequently, and units became infested. Light bulbs were not replaced and a general malaise took hold. That said, Wilson still did not want to leave Cabrini-Green. It was her home.

This was not true for Dawn Knight. Now 48, Knight grew up in the Robert Taylor Homes in the 1980s. Always a good student, Knight recalls spending countless happy hours in the library, a place of respite from her alcoholic mom. Nonetheless, she says that her life began to unravel in 1984 when her brother was shot and killed in their building. “They said the guy was just playing with the gun,” she tells Petty. “I didn’t care. I lost my brother. You know, I was 18 and I’d just had a baby and me and my brother was tight. … We’d gone through a lot. … Back then I was drinking beer and smoking weed to deal with my personal issues, but the night my little brother was killed, afterwards, a so-called friend gave me some heroin. I snorted it and the pain was gone. … The pain just went away. It was downhill from there.”

Knight admits that drug use led to her eviction for nonpayment of rent. In desperate straits, she ended up moving in with her children’s father, a man who abused her. Nonetheless, she believes she got lucky. A chance encounter with members of a Minnesota church who were proselytizing near her building gave her the out she was looking for. She moved to Minneapolis with them, got clean and became a youth pastor. Although she is now back in Chicago, her gaze remains firmly fixed on children and young adults living in dysfunctional or impoverished households. “I let my daughter’s friends know they can always stay [with us] if their family is tripping. I let them know I have to call their moms, but I want them to know they have a place, that they don’t have to smoke or lay with a guy to have a roof over their head,” she says.

Like Knight, 31-year-old Donnell Furlow lacked adult role models when he was coming of age. He lived in Rockwell Gardens and says that he joined a gang when he was in his early teens. “By the time I was in grammar school I was learning how to clean guns, how to shoot a gun, how to hide a gun, how to bag up cocaine and how to shake dope. I had the first of three daughters when I was 13, 14 years old. I had other things on my mind besides school,” he says.

Truant officers seemingly took little notice of Furlow and he speaks matter-of-factly about shooting at cops, robbing people and firing his gun at rivals. What’s more, he tells Petty about corrupt police officers who knew what was going on in Rockwell but ignored it, eager to cash in on the spoils the gangs provided. He further describes instances of overt police brutality.

As for the gang itself, Furlow addresses its appeal. “My parents were there, but they weren’t there,” he says. “I wish I had stand-up parents. I wish I had someone to stand on me to go to school and stuff like that, but I didn’t, so the street had to raise me. … With the gang I was in, there was structure and there were rules.”

Then, in 2005, when Furlow was 24, he was arrested, charged with aggravated armed assault, and sentenced to eight years in prison. He was released to a halfway house in 2011 and is now trying to repair his relationship with his daughters and hold down a job. Despite making enormous life changes, Furlow does not want to relocate. “I want to live where I grew up,” he says. “I have shed blood here just like I have caused blood to be shed over here. … I want to die right here because this is where I’m from. My whole family is here. My history is here.”

Other accounts in High Rise Stories tell complementary tales – of beefs, of friendships, of familial relationships that have nurtured the narrator or caused him or her pain – all of them set in or near CHA-run projects. Some of the testimonies are intensely personal and focus on individual survival, while others look at the impact of community norms on human development and neighborhood cohesion. Throughout, poverty remains front and center.

Petty has put a human face on public housing, offering frontline histories that address the institutional roadblocks and self-sabotage that all too often limit low-income people. City planners interested in addressing urban poverty will find ample fodder here. In addition, activists, politicians and advocates for social justice might use High Rise Stories to ignite a renewed push for federally sponsored housing. For while the CHA and other housing authorities surely made enormous mistakes, the need for subsidized shelter has not abated in the 76 years since Wagner-Steagall became the law of the land.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.