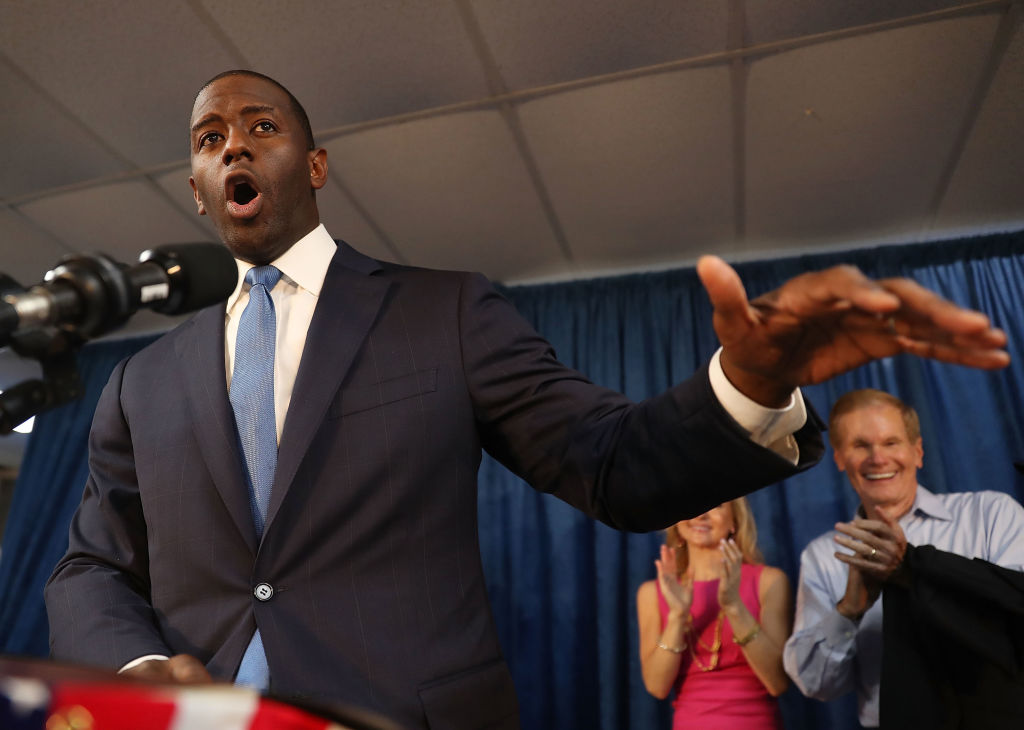

Within of the Andrew Gillum’s upset Democratic primary win to become the first-ever African American candidate for Florida governor, his Trumpite Republican opponent Ron DeSantis warned Florida voters not to “monkey up” the state by voting for Gillum.

The Trump Republicans don’t even try to hide their racism behind so-called “dog whistles” (meaning when politicians use coded language that their supporters understand as racism).

Instead, they reach for the bullhorn.

Championing Medicare for All and supporting calls to abolish ICE, Gillum, the mayor of Tallahassee, defeated a field of “centrist” favorites to win the Democratic nomination. He had the endorsement of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and New York congressional nominee Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Gillum will face a tough fight with DeSantis, who has already shown that he’s willing to go into the gutter to defeat him. But his victory on Tuesday stands out from other Democratic primary races for a couple of reasons.

First, it was a win for the Sanders wing of the party, which has more often fallen short of victory during this primary season. And second, the statewide Democratic vote in this closely divided “swing state” trailed Republican turnout — a break in the pattern this primary season of higher Democratic Party mobilization, compared to Republicans.

This last factor may be just an exception due to competitive Republican primary contests as well. But it’s one of the statistics that political analysts are looking at in assessing the coming midterm elections.

The Building Blue Wave

Through most of the summer, each time a forecaster updated their predictions, it was bad news for Republicans. One analyst, Inside Election’s Nathan L. Gonzalez, predicted that 86 seats in the House of Representatives are “in play” — meaning either main party is given a chance of winning.

Of those 86 seats, Republicans currently hold 76 of them.

It looks like a significant Democratic victory in November — often referred to by commentators as a “blue wave” — is likely. Democrats are the odds-on favorite to retake the majority in House of Representatives.

The Senate will be tougher because of which one-third of senators happen to be up for re-election — three-quarters of the 33 are Democrats this time, and many are from states that voted Trump in 2016. But even here, the Democrats have a shot.

The question analysts are asking now is how high or strong the blue wave will be. Even a leading Republican consulting firm recently reported that four of five standard polling measures that predict a “wave” election are flashing in the Democrats’ favor.

The number of “open” Congressional seats, where no incumbent is running, is the highest since 1930. Since incumbents usually win, and since most of the incumbents not running for re-election are Republicans, this is another advantage for Democrats.

The Democrats have also “overperformed” — that is, received greater support than the historical trends would predict — in special elections held at the state and federal levels since Trump took office.

As of early August, Democratic turnout in primary contests was up 84 percent, while Republican turnout had increased by 24 percent. And in the pivotal races that may decide the majority in the US House of Representatives, Democrats have raised more money than Republicans.

The one indicator that wasn’t yet firmly showing a Democratic advantage — “the enthusiasm gap,” meaning whether Democratic or Republican voters are looking forward to voting in November — was still roughly even in August, and the turnout statistics in Florida aren’t the best news for Democrats.

This means the Democrats can’t count on a lower Republican turnout to win — they are going to have to campaign to get supporters to turn out.

But the Democrats are running a record number of candidates — and a record number of women candidates — at the federal level to entice voters. Just fielding a full slate of candidates means that Democrats can pick up seats, even in places they didn’t contest in the past. This was one reason why the Democrats came within a couple of seats of winning the Virginia state assembly in one of the most-watched off-year elections in 2017.

Progressives Versus the Establishment

If it’s likely that the Democrats are going to win the House, it’s important to ask what a new Democratic House would look like.

The Brookings Institution categorized 681 non-incumbent Democratic congressional candidates as either “progressive” or “establishment,” based on how they identified themselves. Of these, 280 identified as progressive, and 400-plus identified as “establishment.” The gap in the primary winners was roughly similar, going against the progressives.

NBC News’ Chuck Todd made a similar analysis on Meet The Press in early July:

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s win gave a lot of hope to progressives trying to remake the Democratic Party. But if you look at the total landscape, this story is a little different. At this point in the primary season, of the 33 House candidates endorsed by the Bernie Sanders group Our Revolution, 14 have won their primaries, while 19 have lost to the so-called establishment wing of the Democratic Party.

An upstart movement winning 42 percent of its races, that’s actually not bad. However, what happens when you take a closer look at the districts where the Bernie wing is actually winning? Only one of those 14 races is rated competitive by our friends at the Cook Political Report. And even there, the Republican candidate is favored to win.

The majority of these Bernie wins are coming in either safe Republican districts, like Georgia’s 1st, and a few are in safe Democratic districts, where the Democrat would win regardless of who won the nomination.

However, in Democrat-held and “swing” districts — the races where the party leadership is most focused — the “establishment” candidates have tended to prevail.

There could still be a few more surprises in the primaries or in November, especially if the “blue wave” is high enough. But the most likely outcome is a House freshman class that’s going to be pretty establishment-oriented, as an article from the Cook Political Report explained.

“All were against abolishing ICE,” concluded the Cook analysts. “None are talking up ‘a federal jobs guarantee.’ However, like Ocasio-Cortez, they are touting the fact that they won’t raise corporate PAC money. And, like her, they’d like Democrats do more than just fix what’s broken in Obamacare. Most support Medicare for All or a public option.”

Still, overall, Cook concluded, “They aren’t Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.”

This is what the Democratic Party in Congress will look like — and what it won’t look like — if it takes one or both houses this November. Business organizations are already hiring Democratic-connected lobbyists in expectation that at least one house in the Congress will flip to the Democrats.

None of this is surprising. But it does mean that putting the Democrats in charge of the House and/or Senate will empower the “centrist” neoliberal establishment, rather than the Berniecrats or democratic socialists.

Even those candidates who tout Medicare for All are demonstrating the time-honored pattern of turning a concrete demand into a campaign talking point that works to bring people to the polls, but carries no legislative weight.

Is the Party Breaking Up?

What does this tell us about the state of the Democratic Party? Some argue that the internal debate between Berniecrats and the neoliberal establishment portends a crisis, even an impending split in the party.

If “crisis in the Democratic Party” is defined as the party leadership’s continued shock and confusion over losing what they thought was a sure-thing election to Trump in 2016, then one can speak of at least a crisis of confidence among Democrats.

This, of course, has emboldened elements of the party who were critical of Hillary Clinton’s “America is already great” message. But as Perry Anderson astutely pointed out in his postmortem of the 2016 election and the Obama era for New Left Review:

[G]iven how narrowly the party lost in 2016 even with such a deficient candidate, and how brittle the incumbent regime looks, the same kind of common sense suggests that little more need be changed. Assuming that in the interim Trump, unable to deliver better jobs or faster growth, has stumbled all over the place, any halfway decent standard-bearer of a traditional stamp should be able to romp home. Such, at least, is the calculation of the Democratic establishment. Not all sympathizers agree. It underestimated Trump once; for some, it risks doing so again.

Until Ocasio-Cortez’s victory, Democratic leaders had pretty much been able to get the candidates they wanted. And most Democratic voters will vote for any Democrat on the ballot in November in order to protest Trump and the Republicans.

Indeed, the prospect of a “blue wave” in November is forging a certain kind of unity in Democrat ranks. “Trump has been the great doctor, stitching up our scars and healing us organically,” Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, chair of the Democratic Governors Association, told the Washington Post.

It’s inaccurate to say that the Democratic Party is on the verge of a split or an organizational crisis. But it is clear that there is discontent among a significant section of the Democratic voting base over the direction of the party.

This isn’t reducible to the “Berniecrat vs. centrist” axis. There are a number of divisions: generational, for one — whether the Democrats should be more confrontational in their approach to Trump, for another. Not everyone who wants the Democrats to do more to challenge Trump is a Sanders supporter.

There is certainly disillusionment with the existing Democratic Party for not standing up for ordinary people, for being out of touch — for example, the disconnect between a Washington elite obsessed with Russia and a “base” more concerned with health care and inequality.

But for most people who call themselves Democrats, this is much more of a mood or a feeling than an organizing principle. For most, the misgivings could all be reversed with the right liberal candidate — say, Elizabeth Warren — with very little change in the party’s core commitments.

It’s significant that leading 2020 presidential contenders feel they need to endorse Medicare for All, rather than touting their “centrist” credentials. Perhaps that’s a recognition that after 40 years of promoting what Nancy Fraser calls “progressive neoliberalism,” the Democrats (or a significant number of them) see the need to move “left.”

Today, a national health care system and a $15-an-hour minimum wage sound radical in comparison to the still-dominant Clintonite politics in the Democratic Party. But as Ocasio-Cortez pointed out, Democratic presidents like Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman advocated many of these policies more than 70 years ago.

We should be under no illusion about the Democrats’ ability to rehabilitate themselves — and there’s no need to look back beyond 2008 for an example.

The Democratic Party suffered a major defeat in 2004 when George W. Bush, who lost the popular vote the first time, won re-election easily. Pundits were predicting a generation of Republican rule. Yet in 2006, the Democrats swept back to congressional majorities, and in 2008, they won the White House and both houses of Congress.

Millions of people who had given up on the Democrats flocked behind Barack Obama, who despite his commitment to neoliberal orthodoxy, projected a “progressive” image of “hope” and “change.”

The Future of the Resistance

Harvard University sociologist Theda Skocpol has done a careful study of resistance groups in “swing state” counties, and her findings are telling:

We find Bernie voters are in some of these groups…But we don’t find Bernie organizations. I haven’t found even a whiff of Our Revolution. I think that’s mainly a big-city, liberal-area phenomenon…

After every special election, we have another debate. Does Conor Lamb mean that the Democrats are moving moderate? Does [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] in the Bronx mean that they’re moving left? They’re not moving either way. These candidates are suited to their districts, and they’re tied to networks, and they have these groups of women and men in the resistance working for them.

Skocpol’s conclusion, after looking beyond the marquee developments like Lamb and Ocasio-Cortez, is that the electoral resistance to Trump is mostly being channeled into fairly mainstream Democratic Party campaigns.

Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas — who is actually facing a credible challenge to his re-election — has warned fellow Republicans that Democrats “will crawl over broken glass in November to vote.”

That’s absolutely true, but we shouldn’t mistake the urgent desire to vote against Trump and the right wing on the part of millions of people — which is, after all, the latest version of the old “lesser evil” dynamic — with the idea that people are primarily seeing elections as a way to vote “for” things like single-payer health care or free college or even socialism.

While the psychology of Democratic voters in November might not be so overwhelmingly weighted toward the “hold your nose” character of the 2016 election, when Hillary Clinton was the presidential candidate, the logic of “lesser evilism” is still, by and large, the main dynamic.

If the elections put the Democrats in the majority of one or even both houses of Congress, mainstream politics in the Trump era will take on a new form. But whether the Democrats will become more committed to, or more adept at, challenging the Trump agenda remains to be seen.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.