Awá Indians in Brazil’s north-eastern Amazon rainforest know at least 275 useful plants, and at least 31 species of honey-producing bee. Each bee type is associated with another rainforest animal like the tortoise or the tapir.

In the 1980s, the Great Carajás Project opened up Awá lands to illegal loggers and ranchers. More than 30% of one of their territories has since been destroyed.

The Baka have developed sophisticated codes of conservation yet face persecution by wildlife officers. (Photo: Selcen Kucukustel/Atlas)

The Baka have developed sophisticated codes of conservation yet face persecution by wildlife officers. (Photo: Selcen Kucukustel/Atlas)

Baka “Pygmies” of Central Africa eat 14 kinds of wild honey and more than 10 types of wild yam. By leaving part of the root intact in the soil, the Baka spread pockets of wild yams – a favorite food of elephants and wild boar – throughout the forest.

The Baka are taught not to overhunt the animals of the forest. A Baka woman said, “When you find a female animal with her young, you must not kill her. Even worse, when the little animals are walking next to their mother, it is strictly forbidden to kill them.”

But despite their intimate knowledge of their environment, Baka in southeast Cameroon face arrest and beatings, torture and even death at the hands of wildlife officers funded and supported by the conservation giant World Wide Fund for Nature.

A Bushman mother and child gathering berries in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. (Photo: Philippe Clotuche/Survival)The Bushmen consume over 150 species of plant and their diet is high in vitamins and nutrients. Yet Africa’s last hunting Bushmen in Botswana are abused, tortured and arrested when found hunting to feed their families.

A Bushman mother and child gathering berries in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. (Photo: Philippe Clotuche/Survival)The Bushmen consume over 150 species of plant and their diet is high in vitamins and nutrients. Yet Africa’s last hunting Bushmen in Botswana are abused, tortured and arrested when found hunting to feed their families.

A Bushman said, “I know how to take care of the game. That’s why I was born with it, and lived with it, and it’s still there. If you go to my area, you’ll find animals, which shows that I know how to take care of them. In other areas, there are no animals.”

Baiga in India have set up their own project to “save the forest from the forest department” – setting out rules for their own community and outsiders to protect the forest and its biodiversity. As a result, the availability of water supply has increased and they have been able to collect more herbs and medicines from the forest.

A Baiga woman overlooking her tribe’s forest. Thousands of Baiga have been evicted from their land in the name of tiger ‘conservation.’ (Photo: Harshit Charles/ Survival)

A Baiga woman overlooking her tribe’s forest. Thousands of Baiga have been evicted from their land in the name of tiger ‘conservation.’ (Photo: Harshit Charles/ Survival)

The Baiga don’t hunt tigers – on the contrary, they call the animal their little brother – but like many tribal peoples in India, thousands of Baiga have been illegally and forcibly evicted from their ancestral homeland in the name of tiger “conservation,”while tourists are welcomed in.

A Baiga said, “The forest guards don’t know how to look after the tiger. If they see one they bring groups and groups of foreigners to see it. This really harms the tiger, but the park guards can’t see this.”

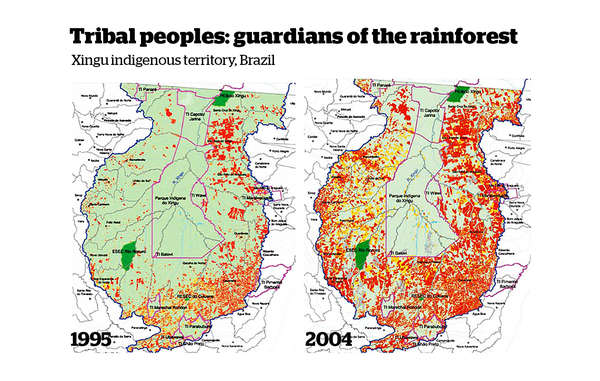

There are many more examples of how tribal peoples are the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world – satellite images and academic studies have shown that indigenous peoples provide a vital barrier to deforestation of their lands. Yet tribal peoples are being illegally evicted from their ancestral homelands in the name of “conservation.” It’s often wrongly claimed that their lands are wildernesses even though tribal peoples have been dependent on, and managed, them for millennia.

The Xingu indigenous park (outlined in pink) is home to several tribes. It provides a vital barrier to deforestation (in red) in the Brazilian Amazon. (Photo: Instituto Socioambiental)

The Xingu indigenous park (outlined in pink) is home to several tribes. It provides a vital barrier to deforestation (in red) in the Brazilian Amazon. (Photo: Instituto Socioambiental)

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said, “Tribal peoples are better at looking after their environments than anyone else – after all, they have been dependent on, and managed, them for millennia. If conservation is actually going to start working, conservationists need to ask tribal peoples what help they need to protect their land, listen to them, and then be prepared to back them up as much as possible. A major change in thinking about conservation is now urgently required.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.