This spring, as California withered in its fourth year of drought and mandatory water restrictions were enacted for the first time in the state’s history, a news story broke revealing that Nestlé Waters North America was tapping springs in the San Bernardino National Forest in southern California using a permit that expired 27 years ago.

And when the company’s CEO Tim Brown was asked on a radio program if Nestlé would stop bottling water in the Golden State, he replied, “Absolutely not. In fact, if I could increase it, I would.” That’s because bottled water is big business, even in a country where most people have clean, safe tap water readily and cheaply available. (Although it should be noted that Starbucks agreed to stop sourcing and manufacturing their Ethos brand water in California after being drought-shamed.)

Profits made by the industry are much to the chagrin of nonprofits like Corporate Accountability International (CAI), a corporate watchdog, and Food and Water Watch (FWW), a consumer advocacy group, both of which have waged campaigns against the bottled water industry for years. But representatives from both organizations say they’ve won key fights against the industry in the last 10 years and have helped shift people’s consciousness on the issue.

A Battle of Numbers

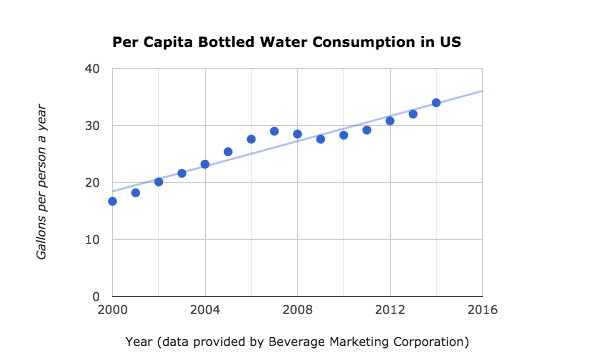

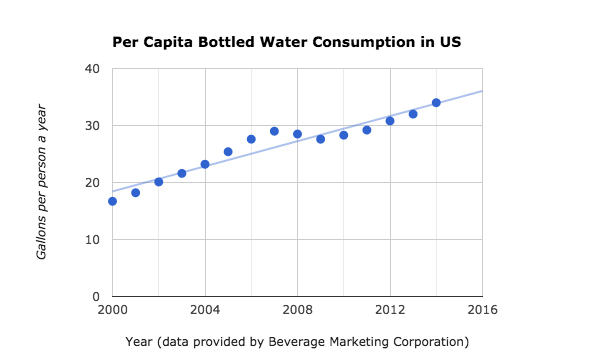

In 2014 bottled water companies spent more than $84 million on advertising to compete with each other and to convince consumers that bottled water is healthier than soda and safer than tap. And it seems to be paying off: Americans have an increasing love of bottled water, particularly those half-liter-sized single-use bottles that are ubiquitous at every check-out stand and in every vending machine. According to Beverage Marketing Corporation (BMC), a data and consulting firm, in the last 14 years consumption of bottled water in the US has risen steadily, with the only exception being a quick dip during the 2008-2009 recession.

In 2000, Americans each drank an average of 23 gallons of bottled water. By 2014, that number hit 34 gallons a person. That translates to 10.7 billion gallons for the US market and sales of $13 billion last year. At the same time, consumption of soda is falling, and by 2017, bottled water sales may surpass that of soda for the first time.

But there is also indication that more eco-conscious consumers are carrying reusable bottles to refill with tap. A Harris poll in 2010 found that 23 percent of respondents switched from bottled water to tap (the number was slightly higher during 2009 recession). Reusable bottles are now chic and available in myriad designs and styles. And a Wall Street Journal story tracked recent acquisitions in the reusable bottle industry that indicate big growth as well, although probably not enough to make a dent in the earnings of bottling giants like Nestlé, Coke and Pepsi.

Why the Fight Over Bottled Water

“The single most important factor in the growth of bottled water is heightened consumer demand for healthier refreshment,” says BMC’s managing director of research Gary A. Hemphill. “Convenience of the packaging and aggressive pricing have been contributing factors.”

That convenience, though, comes with an environmental cost. The Pacific Institute, a nonprofit research organization, found that it took the equivalent of 17 million barrels of oil to make all the plastic water bottles that thirsty Americans drank in 2006 – enough to keep a million cars chugging along the roads for a year. And this is only the energy to make the bottles, not the energy it takes to get them to the store, keep them cold or ship the empties off to recycling plants or landfills.

Of the billions of plastic water bottles sold each year, the majority don’t end up being recycled. Those single-serving bottles, also known as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles because of the kind of resin they’re made with, are recycled at a rate of about 31 percent in the US The other 69 percent end up in landfills or as litter.

And while recycling them is definitely a better option than throwing them away, it comes with a cost, too. Stiv Wilson, director of campaigns at the Story of Stuff Project, says that most PET bottles that are recycled end up, not as new plastic bottles, but as textiles, such as clothing. And when you wash synthetic clothing, microplastics end up going down the drain and back into waterways. These tiny plastic fragments are dangerous for wildlife, especially in oceans.

“If you start out with a bad material to begin with, recycling it is going to be an equally bad material,” says Wilson. “You’re changing its shape but its environmental implications are the same.” PET bottles are part of a growing epidemic of plastic waste that’s projected to get worse. A recent study found that by 2050, 99 percent of seabirds will be ingesting plastic.

“We notice in all the data that the amount of plastic in the environment is growing exponentially,” says Wilson. “We are exporting it to places that can’t deal with it, we’re burning it with dioxins going into the air. The whole chain of custody is bad for the environment, for animals and the humans that deal with it. The more you produce, the worse it gets. The problem grows.”

Even on land, plastic water bottles are a problem – and in some of our most beautiful natural areas, as a recent controversy over bottled water in National Parks has shown. According to Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), more than 20 national parks have banned the sale of plastic water bottles, reporting that plastic bottles average almost one third of the solid waste that parks must pay (with taxpayer money) to have removed.

After Zion National Park in Utah banned the sale of plastic water bottles, the park saw sales of reusable bottles jump 78 percent and kept it 60,000 bottles (or 5,000 pounds of plastic) a year out of the waste stream. The park also made a concerted effort to provide bottle refilling stations across the park so there would be ample opportunity to refill reusable bottles.

There might be more parks with bans but 200 water bottlers backed by the International Bottled Water Association have fought back to oppose measures by parks to cut down on the sale of disposable plastic water bottles. The group was not too happy when National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis wrote that parks “must be a visible exemplar of sustainability,” and said in 2011 that the more than 400 hundreds entities in the National Park Service could ban the sale of plastic bottles if they meet strict requirements for making drinking water available to visitors.

Park officials contend that trashcans are overflowing with bottles in some parks. The bottling industry counters that people are more apt to choose sugary drinks, like soda, if they don’t have access to bottled water. The bottled water industry alliance used its Washington muscle to add a rider to an appropriations bill in July that would have stopped parks from restricting bottled water sales. The bill didn’t pass for other reasons, but it’s likely not the last time the rider will surface in legislation.

Changing Tide

Bottlers may be making big money, but activists have also notched their own share of wins. “When we first started, really no one was out there challenging the misleading marketing that the bottled water industry was giving the public,” said John Stewart, deputy campaign director at CAI, which first began campaigning against bottled water in 2004. “You had no information available to consumers about the sources of bottling and you had communities whose water supplies were being threatened by companies like Nestlé with total impunity.”

If you buy the marketing, then it would appear that most bottled water comes from pristine mountain springs beside snow-capped peaks. But in reality, about half of all bottled water, including Pepsi’s Aquafina and Coca-Cola’s Dasani, come from municipal sources that are then purified or treated in some way. Activists fought to have companies label the source of its water and they succeeded with two of the top three – Pepsi and Nestlé. “We also garnered national media stories that put a spotlight on the fact that bottling corporations were taking our tap water and selling it back to us at thousands of times the price,” said Stewart. “People finally began to see they were getting duped.”

When companies aren’t bottling from municipal sources, the water is mostly spring water tapped from wilderness areas, like Nestlé bottling in the San Bernardino National Forest, or rural communities. Some communities concerned about industrial withdrawals of groundwater have fought back against spring water bottlers – the biggest being Nestlé, which owns dozens of regional brands like Arrowhead, Calistoga, Deer Park, Ice Mountain and Poland Spring. Coalitions have helped back communities in victories in Maine, Michigan and California (among other areas) in fights against Nestlé.

One the biggest was in McCloud, California, which sits in the shadow of snowy Mount Shasta, and actually looks like the label on so many bottles. Residents of McCloud fought for six years against Nestlé’s plan for a water bottling facility that first intended to draw 200 million gallons of water a year from a local spring. Nestlé finally scrapped its plans and left town, but ended up heading 200 miles down the road to the city of Sacramento, where it got a sweetheart deal on the city’s municipal water supply.

CAI and FWW have also worked with college students. Close to a hundred have taken some action, says Stewart. “Not all the schools have been able to ban the sale of bottled water on campus but we’ve come up with other strategies like passing resolutions that student government funds can’t be used to purchase bottled water or increasing the availability of tap water on campus or helping to get water fountains retrofitted so you can refill your reusable bottle,” says Emily Wurth, FWW’s water program director.

Changes have also come at the municipal level. In 2007, San Francisco led the charge by prohibiting the city from spending money on bottled water for its offices. At the 2010 Conference of Mayors, 72 percent of mayors said they have considered “eliminating or reducing bottled water purchases within city facilities” and nine mayors had already adopted a ban proposal. In 2015, San Francisco passed a law (to be phased in over four years) that will ban the sale of bottled water on city property.

These victories, say activists, are part of a much bigger fight – larger than the bottled water industry itself. “We are shifting to fight the wholesale privatization of water a little more,” says Stewart. He says supporters who have joined coalitions to fight bottled water “deeply understand the problematic nature of water for profit and the commodification of water” that transcends from bottled water to private control of municipal power and sewer systems.

Currently the vast majority (90 percent) of water systems in the US are publically run, but cash-strapped cities and towns are also targets of multinational water companies, says Stewart. The situation is made more dire by massive shortfalls in federal funding that used to help support municipal water and now is usually cut during federal budget crunches.

“Cities are so desperate that they don’t think about long-term implications of job cuts, rate hikes, loss of control over the quality of the water and any kind of accountability when it comes to how the system is managed,” says Stewart. “We need to turn all eyes to our public water systems and aging infrastructure and our public services in general that are threatened by privatization.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.