Millennial voters have gotten a bad rap when it comes to politics. They’re often brushed off as self-obsessed and disengaged, a stigma rooted in their abysmal turnout in recent elections. Just 21 percent of millennials voted in the 2014 midterms.

Millennials will make up about 31 percent of the electorate this year.

But the 2016 election season has put that stereotype into question. Millennials will make up about 31 percent of the electorate this year (up from 18 percent in the 2012 elections), and are poised to play a decisive role in many states. For the first time, their numbers will match those of the baby boomers.

With that kind of clout, it’s no surprise presidential candidates are talking about the issues young voters care about most, like the minimum wage and student debt. But what happens once the polls close and the election is over? How do young people hold politicians accountable after they’ve cast their votes?

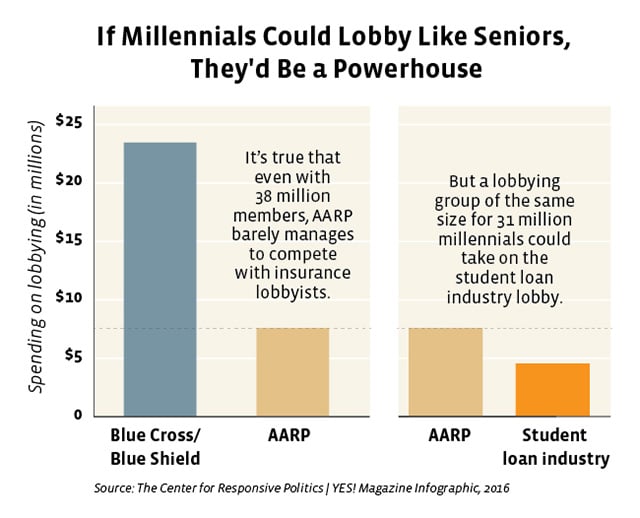

Right now, they don’t. Most voting blocs (like seniors, African Americans, or conservationists) use lobbyists and advocacy organizations to make their voices heard. Young voters haven’t had that option — until now.

The Association of Young Americans (AYA) is a fledgling nonprofit that aims to represent Americans between 18 and 35 years old in policymaking. “You can think of it as an AARP for young people,” says the organization’s founder, Ben Brown.

“Companies, unions, even our parents have lobbying organizations,” he says. “After they vote, they continue to have representation every day.”

The AYA functions a lot like AARP, formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons. It’s based on a membership model, in which individuals pay $20 a year to support the organization. Those dues pay for professional lobbyists to represent the group’s interests, and members gain access to discounts (currently, perks include savings on mattress delivery and on a brand of “caffeine-enhanced energy tea”). Launched a month ago, AYA is developing partnerships and growing its member base, which so far is in the “low hundreds,” according to Brown. The group won’t begin lobbying until after the November elections, when members of Congress return to business as usual.

Brown, 27, graduated from Middlebury College in 2011 with a B.A. in physics. He’s based in New York City and previously worked as an analyst for several clean-energy companies. He got the idea for AYA three years ago, after reading an article in The Washington Post that quoted U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wy.) talking about young people’s lack of political power. The senator had said that nothing would change until a young person “could walk into his office and say, ‘I’m from the American Association of Young People. We have 30 million members, and we’re watching you, Simpson.'”

That’s exactly what Brown wants AYA to be: enforcers working on behalf of young people.

Millennials are especially in need of political access because they face a unique set of economic pressures.

Lobbyists are often frowned upon for doing the bidding of major corporations. A list of the organizations that spend the most on lobbying, maintained by the website OpenSecrets.org, is full of corporations like Boeing, General Electric, and AT&T, as well as associations like the National Association of Realtors.

But lobbyists also represent retired people, unions, and graduate students. “Lobbying shouldn’t be a bad word,” says Mark Huelsman, senior policy analyst at Demos, a think tank that researches issues including democracy.

Huelsman says millennials are especially in need of political access because they face a unique set of economic pressures — from a changing job market where pensions are hard to come by to a lack of affordable housing. Take student debt: Universities and lenders have the resources and tools to lobby policymakers, while students, despite being the most affected, don’t have a voice in the matter.

“There has to be a big, wide, concerted effort to show state legislatures, Congress, even the White House that things really are different for this generation,” says Huelsman.

Untapped Power

An assembly of young people would have been harder to achieve 10 years ago, Brown says. That’s partly because there wasn’t as much alignment on the issues among young voters, but also because the tools to organize such a widespread group of people were not as advanced.

“We’re really hoping to bring lobbying into the 21st century,” says Brown. He envisions a system where members can communicate with lobbyists and be brought into their conversations with representatives through live streams and social platforms.

That kind of involvement is exactly what members hope the group will provide. Christopher Whalen, 26, is a communications manager for the Credit Union League of Connecticut. He says he joined AYA because he knows firsthand that advocates can make a difference and believes the group will give young people a way to be involved in politics year-round. “We tend to be a generation that can get hashtag campaigns trending, but we often have a problem taking that passion and turning it into strategy,” says Whalen. “Change doesn’t happen every four years. It’s an everyday thing.”

Gabriella Rebata, an 18-year-old high-school senior, shared a similar sentiment. “Young people aren’t interested because they think they’re just one vote,” she says. “They don’t see how much power they actually have.”

More Than Just an Age Group?

Getting young people to join forces is an ambitious goal, especially since millennials have tended not to vote in recent elections.

That’s part of what makes this project an “uphill battle,” says Matt Grossmann, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan University and author of a book about interest groups in American politics. He studied 140 lobbying groups in the United States and found the most successful ones were organized around a specific cause or policy issue and had members who were already engaged in the political process.

“You can say that you’re speaking for young people as a whole, but that’s not how policymakers see it,” says Grossmann.

AARP, for example, developed out of a specific campaign to secure health insurance for older Americans. The group also was independently useful to members because it offered essential discounts and services. Plus, seniors’ high turnout gave the AARP leverage with lawmakers.

Brown believes that young people have the potential to wield that kind of clout. For one, a Pew Research Center study shows that half of millennials reject party affiliations and consider themselves independent, more than any other generation.

AYA asks members to fill out a survey about the issues most important to them. Across the board, members expressed concern with student debt, campaign finance, and criminal justice reform. So millennials have more in common than just their age.

“I think the common thread is a burning desire among young people for honesty and transparency in government,” says Brown. “For America’s wealthiest corporations to have this tool to push their agenda every day is not equal-opportunity, and I think that idea unites young people.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.