Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

It’s a Thursday afternoon and Romero Jackson is busy mapping outreach plans for Milwaukee’s North Side, home to some of the city’s youngest and hardest to reach potential voters. At 25, he’s the field director for the Campaign Against Violence, the Wisconsin-based arm of the League of Young Voters. Today he’s jockeying between his laptop and stacks of voter pledges, while trading jokes around the room about what might help him grow taller. At barely 5-foot-5, Jackson’s got a slight build with smooth dark skin and short dreadlocks that trail his every move.

His words are nervous at first, but come easily once he’s comfortable. It’s that self-assured vulnerability that likely draws people to him, making him seem much bigger than he really is. And with less than two weeks left until the state’s big midterm elections, he’ll need all the charm he can muster to bring voters to the polls. Enthusiasm for the election in this part of town is in short supply.

The recent redevelopment of downtown Milwaukee isn’t visible in the North Side. Dr. Martin Luther King Avenue, the area’s main thoroughfare, is adorned with a healthy dose of Pentecostal and Baptist churches, a candy store, a few cell phone depots—and lots of empty storefronts for rent. Either side of the boulevard is surrounded by modest family homes whose lawns occasionally betray their owners’ political leanings. A stately brick home with a freshly manicured lawn boasts signs for local Democrats. Just a few minutes down the street, another home has got a sign up supporting the Republican gubernatorial candidate, Scott Walker. That Republicans have a foothold even in North Side is an indication of how disastrous the midterm elections have turned out for Wisconsin Democrats.

For Jackson, this year’s election is a big one, too. It’s his first time voting; he couldn’t cast a ballot in 2008 because he was on probation. Not that it stopped him from canvassing with friends and talking to neighbors about why Barack Obama needed to be elected president. Jackson was one piece of the energy that generated an historic black-youth voting wave in 2008—one that helped create a new generation of voters that was widely expected to permanently change electoral politics. Youth organizers like Jackson helped draw in millions of eager, young black voters in record numbers.

This year, Jackson has taken to the streets with new vigor. From Monday through Saturday, he and a team of paid interns spend at least five hours each day canvassing, phone banking, or promoting events to get out the vote. Jackson’s one of the oldest of the group, while the rest are just a few years out of high school and not necessarily intent on college. They’re all friends and cousins who’ve mostly grown up together, and are slowly becoming politicized through their efforts to get out the vote.

In many ways, Wisconsin is ground zero for the massive shifts currently shaking up the nation’s politics. Democratic gubernatorial candidate Tom Barrett and Sen. Russ Feingold, a Democratic icon to many, are both in pitched battles that have become national symbols of the party’s peril this year. Milwaukee and its black vote turnout is key to giving either candidate any serious shot at victory.

Of course, as a 501c(3) non-profit, federal law prevents Jackson’s voter-outreach group from openly endorsing any candidate. But that’s just as well, because neither party has captivated this cadre of canvassers, or the many people they talk to each day. Instead, they’re focusing their energy on the more basic concept of civic participation. And they’re using more basic tools, too—promoting a mixtape that encourages youth turnout, throwing a Halloween-themed party that’s aimed at getting families excited to go to the polls.

Jackson himself admits to being only “kinda sorta excited” about this year’s candidates. He met Tom Barrett at a recent lunch, but his most memorable political experience came the day he convinced 15 guys standing on a North Side corner to fill out voter pledge forms. It was a small but important moment that proved that his efforts could have a direct impact on his community, he says.

“If no one gets out to vote, it’s gonna stay the same,” Jackson says. “Like a Twilight Zone.”

There’s something intangible that makes this year’s election different than most. For many, Barack Obama’s candidacy brought to the forefront a new, more accessible form of democracy. There was a massive communications network that engaged voters online, on the phone, and on their blocks. And there was Obama himself: a man of color who seemed to code switch his way from Chicago’s South Side to Harvard, who talked openly about racial profiling and boasted having Jay-Z on his iPod. He was a well-packaged newcomer who looked, talked, and presumably saw the world through the same eyes as many young people of color. And those eyes weren’t accustomed to the view from the White House.

Though Obama himself warned that his brand of change would be a gradual one, his election inspired many young voters—particularly African Americans—to engage in a political process from which they had long felt alienated. African-American young people voted in unprecedented numbers; their generation was believed to have come of political age in 2008. They had grown up alongside civil rights lore, had been told from birth that they were benefiting from decades of racial, economic and gender struggles that all seemed to culminate on election night in Chicago’s Grant Park. It’s unclear whether young voters themselves were ever willing participants in that narrative. But what’s certain is that two years later, the story arc has become decidedly less triumphant. In cities like Milwaukee, one pervasive question stands above the rest: What has happened to hope?

But youth voter advocates warn that’s the wrong question altogether. If you want to get young people of all colors involved, they say, it’s crucial to understand what drives them into politics. And more often than not, it’s got little to do with partisan campaigns or any particular candidate and much more to do with feeling that they’re heard and can control their own destinies.

A New Generation of Voters

It’s a rainy Saturday morning and nearly 200 people have gathered in downtown Milwaukee’s Red Arrow Park for a rally. With less than two weeks left before Election Day, people have gathered their small kids, big jackets, umbrellas and campaign signs to line up along the park’s concrete and listen to the state’s embattled Democrats make their cases.

Each candidate is there to encourage voters to cast ballots early, a tactic that’s proved increasingly successful for Democrats. Wisconsin Rep. Gwen Moore tells the crowd to stop “drinking the poisoned tea,” a reference to the emergence of the GOP’s tea party backed candidates Scott Walker and Ron Johnson. Tom Barrett, the city’s current mayor who’s locked in a tight race for governor, rambles his way through a story about discontinued bus lines near his Milwaukee home before settling instead for a sports analogy. “This is the fourth quarter of an NBA basketball game,” Barrett yells. “Their whole bet is that you stay home. I want them to lose that bet!”

Finally, crowd-favorite Feingold takes the stage. An 18-year incumbent, Feingold’s career has been characterized by his frequent breaks with party lines. In 2001, he was the only senator to vote against the Patriot Act. Campaign finance and health care reform are both issues that he proudly champions, despite widespread public backlash. But in a tough election season that’s proven hostile to incumbents, Feingold’s fighting for his political life against Johnson, a plastics manufacturer and tea party favorite who this week has a 2-point lead in the polls.

Still, Feingold knows what appeals most to his base. “There’s a ranking of senators that came out recently on Capitol Hill,” he tells the crowd. “Who’s the hottest, who’s a gym rant? I was none of those things,” he jokes. “But I was voted the number one enemy in Washington!” The crowd loves it.

David Crowley loves it, too. He’s been crisscrossing the crowd all morning, setting up speakers and shaking hands. At 24, Crowley is a field organizer for the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, and a former employee of Feingold’s who once headed the senator’s African-American outreach committee. He credits Feingold’s rebellious approach to keeping him interested in politics. A few minutes later, when about a third of the crowd ventures up the street to cast early ballots, Crowley’s there snapping pictures on his camera phone. “This turnout is great,” he says, smiling. “Even better than we expected.”

A day earlier, Crowley sat at a restaurant and explained why, for him, the role of Democratic Party operative didn’t seem likely. Born and raised in MIlwaukee, he recounts how both of his parents battled addiction and an older brother was diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic. He describes himself as a “rough-and-tumble kid” who popped pistols and flirted with selling drugs until he joined Urban Underground, a youth development organization, in high school. That’s when he began to see himself as part of a solution. He began leading workshops on the prison pipeline that was quickly swallowing many of the state’s black youth (“We went from herding animals to herding people,” he jokes) and began studying education at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, before taking a leave from school and getting involved in politics.

These days, Crowley jokes about his lack of a social life. A typical day starts just after dawn and ends shortly before midnight. His day is filled with door-to-door outreach, conference calls and emails, all in an effort to bring more people to the polls on Nov. 2. He estimates that he talks to an average of 200 people each day, and lately, their reactions have been mixed. Most people he runs into don’t know much about this year’s midterm elections, and know even less about their state’s pivotal role on the national political map.

“This election isn’t about Feingold or Barrett, ” he says over breakfast. “It’s about Obama.” Later, he hones in on his point. “All I’m trying to do is build a structure for 2012, because it’s not going to be as easy as it was [in 2008], if this year is any indication.”

That line may move some voters, but it doesn’t work on many. Particularly, he says, younger ones, who point out that their fortunes haven’t changed with a black president in office. It’s a strikingly changed attitude for a state that ranked second in youth voter turnout two years ago.

On Sept. 28, President Obama kicked off his national outreach to young voters with a speech at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. It was an indication of just how crucial Wisconsin’s young electorate is to Democrats. Obama warned the crowd against dropping a ball that was almost certainly in their court. “The biggest mistake we could make is to let disappointment or frustration lead to apathy. … That is how the other side wins,” he told a crowd of 26,000 supporters. “If the other side does win, they will spend the next two years fighting for the very same policies that led to this recession in the first place.” CNN noted that the rally lacked the excitement of 2008, and the Washington Post declared that the mood of the day was “upbeat but controlled.”

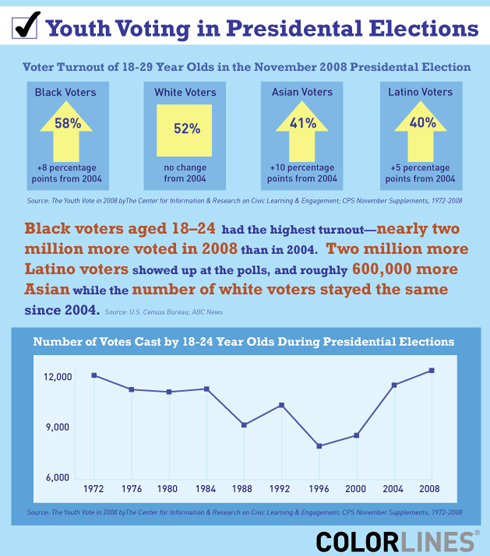

Young voters, particularly those of color, have become increasingly important to the nation’s elections. In 2008, 68 percent of voters under 29 chose Obama, continuing a trend from 2006 in which nearly six in 10 young voters supported Democrats. But Obama’s election was a record-breaking moment for black and Latino voters, as the youth vote helped close the long-standing black-white gap in turnout.

According to the latest Census figures, black youth had the highest turnout among voters aged 18-24 of any ethnic group, and nearly two million more voted in 2008 than in 2004. Two million more young Latino voters also showed up at the polls, and roughly 600,000 more Asian-American voters. Meanwhile, the polling rate among young white voters stayed the same as 2004.

Crowley acknowledges that this year is likely to look much different. The election of the nation’s first black president, which drove many to the polls, is no longer a dream but rather a reality that’s not all that different from the past. Youth unemployment, particularly in post-industrial cities like Milwaukee, remains high. The country’s political climate has grown increasingly hostile and polarized along racial lines. There’s the ascendance of the Tea Party, the defeat of the DREAM Act, which would have opened a path to citizenship for undocumented youth, and the shelving of comprehensive immigration reform.

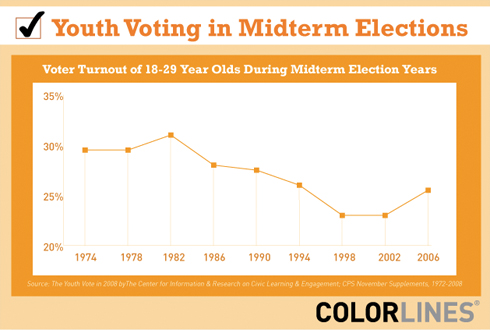

And history isn’t exactly on the side of good turnout: For one, it’s a non-presidential election, meaning that voters of all ages are expected to turn out in far lower numbers. So far, statistical projections have varied wildly. On one hand, Rock the Vote, a political engagement hub for young voters, is expecting a 76 percent turnout among all youth. Meanwhile, the Pew Research Center estimates that only 45 percent will show up to the polls on Election Day. And even in a comparatively good year like 2006, only 25 percent of young people came out to vote. The highest turnout on record for voters under 20 was 1982, when 31 percent cast ballots.

But coupled with these already low expectations is the belief that Democrats in general, and President Obama in particular, have lost sight of what inspired the nation’s young electorate to rally behind them in the first place: The promise of tangible change for their lives and their communities.

What Have You Done for Me?

Milwaukee recently emerged as America’s fourth-most impoverished big city, a statistic that’s mostly concentrated among the city’s black and Latino neighborhoods. Like other cities on the list—Detroit was first, followed by Cleveland—Milwaukee is a mostly black, midwestern town struggling to find a post-industrial economic identity. While the downturn is at least partly to blame, it’s not the only culprit; factory jobs here have been disappearing for the better part of three decades. That prolonged chokehold comes with a host of concomitant effects: in the 1990’s the city’s murder rate was among the highest in the country and earned it the unenviable nickname “Kilwaukee.” And Wisconsin leads the nation in its incarceration rate of black men, a rate that’s more than 10 times that of whites.

“This state is like a donut hole,” says Denise Neylon, 57, who’s black and has worked as a special-service attendant at the Frontier Center for the past five years. “All the resources come into Milwaukee, and then they’re sucked out to the suburbs.”

It’s exactly this sentiment that’s become a prevailing narrative in this year’s governor’s race. Wisconsin has lost 180,000 jobs during the recession, and a big part of Republican Scott Walker’s economic recovery plan is eliminating $1.8 billion in tax increases approved last year by the state legislature. Progressives fear he’ll also do away with the state’s signature BadgerCare health insurance program, which provides low cost insurance to thousands of the state’s poorest residents. Barrett, who was born and raised in Milwaukee, has tried to rev up the city by painting Walker as an outsider from Wauwatosa, one of the city’s affluent white suburbs. He says Walker’s just riding the waves of conservative populism without any true sense of how to govern a state whose economic ship is sinking.

But it’s not a job that Barrett has convinced many here he’s worthy or capable of, either. Nearly 15 years Walker’s senior, Barrett’s got a nervous, uncertain way about him in public, a look that can lead some observers to question whether he really wants the job. His speeches don’t captivate crowds and, judging by Milwaukee’s current troubles, it’s not clear to the city’s voters that his policies will either. The ambivalence shows statewide: Barrett’s trailing Walker by 10 points, according to the latest Rasmussen poll.

Barrett’s also got a tenuous relationship with the city’s black community. He captured the mayor’s office in 2004 after defeating Marvin Pratt, the city’s first black mayor. Pratt held a commanding lead until the final weeks of the race, when Barrett surged. Members of the black community argued that Barrett’s last minute comeback was buoyed by the city’s long-standing racial divide. They accused the media, namely the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, of turning white voters against Pratt. This year, Pratt’s endorsing Walker for governor.

Along Dr. Martin Luther King Avenue, where Romero Jackson begins his outreach every day, the rifts from that debate are still visible. Many 2008 voters, young and old, held out hope that a new economic order would come to the North Side with the new political order they created. It didn’t. And now their enthusiasm is proving as tenuous as the recovery. Just whose fault that is depends on who you ask. There’s a sense that Milwaukee’s black community feels left behind by broken Democratic promises of revival.

Crowley also testifies that it’s been hard to recruit black organizers. First, he says, it’s hard to find young African Americans who are trained in the type of political organizing that’s necessary in a campaign season. But perhaps more importantly, it’s been tough to convince young black organizers who do have experience that it’s worth investing in the Democratic Party. The hours are long, the pay is meager, and they’d likely have to sacrifice time and energy away from their communities and school to invest in a party that tends to only show up during election season.

“We don’t hold Democrats accountable,” Crowley says. “We need to challenge candidates to take on our issues. What are we giving them to do?”

On the south side of town, immigrant rights activists are grappling with similar questions.

“There’s this rising wave of anti-immigrant sentiment and it needs to be battled, especially in a society that talks about being founded by immigrants,” says Maricela Aguilar, a 19-year-old undocumented junior at Marquette University.

Aguliar has spent the past several years jugging school, a waitressing job, and political work with Voces De La Frontera, a Milwaukee-based immigrant rights groups. After successfully working on an effort to grant undocumented students in-state tuition, she’s been actively involved with a national network lobbying for the DREAM Act, which Feingold co-sponsored earlier this year, before it was defeated in the Senate.

“People got really caught up in the sentimentality of hope and change [in 2008], and I think now they’re disillusioned, especially in the Latino community,” she says, citing President Obama’s reluctance to throw his full weight behind comprehensive immigration reform and the DREAM Act.

“We need really good elected officials to push legislation that needs to be passed,” she says. Aguliar adds she’s not interested in whether Feingold has magical charisma (which he doesn’t). She’s involved because he’s actively worked on issues that could have profound impacts on her life.

Tunnels to the Future

Both parties have vested interests in reaching out to voters while they’re young. Studies have shown that people across the political spectrum are likely to stick with the party that they’re drawn to in their early years as voters. And while that’s worked in Democrats’ favor recently, since younger voters have tended to be more progressive over the past 20 years, it could also turn against them, if failure to deliver results drives a whole generation out of electoral politics altogether.

The challenge isn’t just the economy, youth organizers say. “Mudslinging turns people off,” says Karlo Barrios Marcelo, a Chicago-based political consultant and former researcher for the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, which studies youth voting. “To engage young people, you have to ask what they want, and how they want to get involved.”

While 2008 was framed largely around a message of unity, 2010 has been characterized by a rise in political extremism.

“There’s a sense of, ‘We don’t have to give into this partisan political hackery,’ ” says Christina Hollenback, director of Generational Alliance, a national voter coalition. “We can do better, and don’t have to take part in this craziness.”

But if there’s a quantifiable difference between this year’s election and 2008, it’s resources. Marcelo notes that from his bird’s eye view, candidates haven’t put the time and energy into courting young voters, and there’s not been much of the type of innovation that piques the curiosity of those looking for something new to engage. He suspects that will change over the next two years as both parties prepare for the 2012 presidential elections. The question is whether that’s too late.

Still, the unforgiving reality for both parties is that the country is trending toward a more diverse electorate, and today’s young voters will be at its core. People of color now make up two-fifths of all kids under 18, and demographers estimate they’ll be a majority by 2023. As this electorate grows more prominent, so do the issues that matter most to them. “We can’t deny demographics,” says Marcelo. “They are our destiny.”

The secret to claiming that destiny was evident the night before the Democrats’ early-voting rally at Red Arrow Park. Just a few blocks away, Urban Underground, the organization that helped give Crowley his start, was celebrating its 10-year anniversary. There was a sparse, but energetic crowd. There were testimonies from former members who, like Crowley, credited structure and mentorship for their literal survival. There were poems about taking agency, and a rousing appeal by Alderman Joe Davis to think globally about business and remember the power of God. And then there was a final award of the night, presented at the event’s closing by executive director Sharlen Moore. Perhaps not surprisingly, she called Crowley up to the stage.

It was a moving moment, but also notable because neither the election, nor Crowley’s role in it, came up.

“You’ve always been there,” Moore told the young Crowley. “When money’s been tight or someone needed a ride to go get shoes for the prom. More people should be like you.” To that, Crowley raised an eyebrow and nodded his head slowly, as if to say, yeah, more people should.

Wisconsin’s Democrats would agree. But if they want to tap into the Crowleys of the world, they’ll have to first understand he’s more ally than operative. When asked the day before to broadly describe what he does, Crowley called himself more of a “tunnel builder than a bridge builder.” “Tunnels last longer,” he said. “And don’t everybody need to see what I’m building.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.