Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

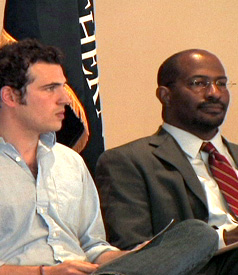

On Monday, March 22, Van Jones and Billy Parish appeared together for a presentation entitled “Challenging America: Achieving Sustainability and Justice Through the Green Collar Economy” at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. The former Obama administration Green Jobs Adviser, Center for American Progress Senior Fellow and author of “The Green Collar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems” and the Yale drop-out founder of the Energy Action Coalition and Clean Energy Corps provided a demonstration of the signature mix of inspirational vision and practical rigor that characterizes both men’s work in support of environmental responsibility, diversity, social justice and democracy.

Billy Parish began his presentation by asking whether Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., Joseph McNeil and David Richmond were present in the hall. No one stood up.

Billy Parish went out on a limb at a recent NAU presentation to put in a word for unpopular international climate reparations. (Photo: John Christopher Strobel)

“Brother Billy” – as Van Jones occasionally referred to him – proceeded to provide a rough sketch of his own trajectory from the safety and predictability of a privileged background to the decision to come “off the tracks” and plunge into committed organizing. He compared being alive now to coming of age at the cusp of the agrarian or industrial revolutions – or in the late 1950’s, as the civil rights struggle was poised to take off. He described the green economy revolution as the only way to reconcile the crisis in resource availability and the social justice requirement to provide jobs for all the billion people poised to enter the global job market over the next three years. A steady-state economy will exhaust global resources of every kind and provide only 300 million jobs for those billion people, while transforming every system on which our economy depends “from how food is grown and processed, to how energy is delivered, to how we do the laundry” could create jobs for all.

Parish cited specific initiatives in Northern Arizona – the creation of green affordable housing for Navajo elders and a local burger restaurant that serves sustainably raised local food only – as examples of what needs to happen and can happen. He closed his prepared remarks with the reinvocation of the four young African-American freshmen at the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina who entered the Greensboro Woolworth’s and sat down on stools previously reserved exclusively for whites and pointed out that, “Acts of courage inspire courage,” that we have a very small window only to reverse climate change, and, finally, that “every single one of us is part of the problem. Every single one of us can be part of the solution.”

Van Jones began his prepared remarks by addressing them exclusively to the “weird” students and the “sensitive” students, those who are uncomfortable with the fact that an increasing number of people have “no jobs and no hope of jobs” that people around the world suffer and struggle. “Something about this is calling to you, but you don’t know what to do. Well, you’re not alone.”

Jones declared, “We can solve the two biggest problems you’re ever going to face in your lives with the same solutions.” Although it’s going to look as though there a lot of different problems, there really are only two:

1. An incredible long-term, structural, economic crisis.

2. An extreme ecological crisis.

Van Jones drove home the fact that living in a diverse, fair and sustainable society means that every single person must give up something. He offered anger as an example. A questioner suggested meat would be a good start. (Photo: John Christopher Strobel)

Jones exhorted students to make a difference on both fronts simultaneously and told them, “If you try to solve one without the other, you’re going to get an ‘F.’ You can get economic growth on a resource-stripped and more violent planet.” You can solve the ecological crisis: “Everybody just stop. Everybody just starve. Everybody stop traveling … and after you fall over, the little worms will eat you and the earth will be happy.” The good news, according to Jones, is that “there is an answer. The bad news is that it’s too big for you to do by yourself.” Jones referred to the US as “the Saudi Arabia” of solar and wind power, the home to some of the most skilled workers in the world – sitting idle. “Why should they be sitting idle in your country? Why should we have 10 percent, 5 percent or even 1 percent unemployment in this country when there’s all this work to be done?” Jones is excited by wind turbines (“8,000 finely machined parts”) which he sees as part of the solution to rural hardship. People who own land and are suffering, who are losing their land because they can’t make a living “could have three sources of income:”

1. Wind turbines.

2. Growing smart energy crops.

3. Sequestering carbon in the soil.

“We could bring our agricultural heartland back in America if we had a smart energy policy.”

The Watts teenager holding a handgun and standing next to a house with no insulation could be standing on the roof of that same house within a year – installing solar panels, installing insulation. There’s no reason in the world why the 100 million homes in America that can be profitably upgraded to save energy, materials and water should not be.

“Why should we have one percent unemployment? Because we lack something in this country at sufficient scale: feeling for country, feeling for other people…. Now I’d like you to notice that nothing I’ve been talking about today requires anyone to change their political party.” It’s all about making America stronger for the long term, about being a leader, not a follower, among nations. “We can choose to let other nations lead on this. China is spending $12 million an hour to develop alternative energy sources.” We need friendly competition – “coopetition” – to repower the earth. “I want China to succeed; I love China; they have people living in misery …” Jones just wants to make sure we get our fair share of the jobs created by this great transition and that everyone in the US has a fair shot at those jobs, including people in Appalachia, in Watts, on the Native American reservations.

Jones reverted to this theme later when a question arose about stimulus funds that went to Chinese industries: Of the $80 billion in the recovery package, almost all went to the US, however, “If we are not careful, everything you fear and much worse will come to pass. America as a whole is in great danger because global production capacity for wind turbines is about to be frozen in place,” primarily in Asia. Private capital decides where to build factories. But there’s no renewable energy standard in the United States, while it’s state policy in China. “If you want to attract the private capital, you have to get the public policy right.” A much more aggressive renewable energy standard and goal would bring in a tidal wave of private capital, he asserted.

Asked to provide examples of cost-effective green revitalization efforts in areas hit by disaster such as New Orleans, Jones noted that there are “people drowning on dry land who have been knocked over by economic tsunamis” and admitted that green movement activists have been caught unprepared while corporations are completely ready to mobilize “just waiting for something bad to happen,” something, Jones notes, that we can’t be shocked by any more. “We need to do a better job at consolidating our resources…. We need to be ready to put together much bigger, more sophisticated proposals.” Green movement organizations need to spend less time fighting one another and get together and get ready.

In response to the same question, Parish cited Cleveland’s “evergreen cooperatives,” including a cooperative laundry and a huge indoor greenhouse, as models that could be replicated. He pointed out that US communities hit by disasters are still wealthy and well-prepared relative to global counterparts and that some part of global environmental preparedness must include some form of – most unpopular in the developed world – international climate financing. In response to a question about green projects on Native American reservations, Parish acknowledged the necessity to find syntheses between traditional lifeways and the economy, between high tech, green tech and traditional tech. He highlighted the real risk of the clean energy revolution following the colonial model of prior energy regimes and warned that policies must be changed so that tribes can become equity owners of energy projects situated on tribal lands.

Asked how organizers overcome many people’s sense that structural equals insurmountable, Parish advocated broadening coalitions and reminded listeners that Campus Climate Challenge had mobilized hundreds of students and at least 50 organizations that work with young people, but had very little to show for it after two years. The breakthrough occurred when they created a larger set of stakeholders by partnering with a college presidents’ group. All key people need to be involved.

Van Jones referred to another aspect of the history of creating social change. “In Birmingham, maybe 15 percent of the African-American community was involved.” The way human society is organized, “somebody’s always gotta be dealing with other stuff.” However, “we’re going to be doing this a long time. This is a major turning point in human civilization.” He exhorted students to develop the skill set now that will serve them whatever they do the rest of their lives, to “stick with it” and recognize that those who complain the most are also often achieving the most. The skills developed through social activism are applicable in all walks of life and every profession.

Asked about “eco-apartheid,” Jones responded forcefully, “At the end of the day, this is a moral movement. It’s way too late to imagine we can have an industrial movement without a moral center. We don’t behave as though we have throw-away children or throw-away resources…. In Chicago [where today, Green Corps is teaching people – many of them former inmates of correctional institutions – how to retrofit buildings, plant gardens, etc.], people had been thrown away. If we’re willing to give a plastic bottle a second chance, I can’t understand our not being willing to give a fellow human being a second chance.” Parish pointed to model green job creation policies in Portland and the Massachusetts “Commonwealth Challenge,” as well as Property-assessed clean energy (PACE) bonds, now used in fifteen states (but NOT Arizona yet) to finance complete home retrofitting and other local clean energy initiatives as examples of programs that have promoted social justice and diversity as well as energy transformation.

One panelist pointed out that the virulent attacks on Jones while he was employed within the Obama administration were also attacks against the idea of green jobs and the idea of sustainable communities. “What makes for the strength, the resonance of that backlash? If this isn’t appealing to a wide variety of people what can be?” Jones began with the statesmanlike admission that “Anything that is new has to go through a period of being misunderstood…. Federal commitment to green jobs – at least in its present articulation – is less than three years old,” and moved on to the ironic observation, “My colorful career makes me a pretty fun target.” Then he pointed out that the call for green jobs should makes everybody happy: progressives get “poor people, the bunnies, and the trees,” while conservatives should like it that there are no more demands for welfare, but rather for work; nor for entitlements, but rather for enterprise. “This is common ground. Whether I have a job in the White House, the greenhouse or the dog house, this will still be the prize: jobs and reborn communities.” Generals are actually beginning to talk about this issue as one of geopolitical security. “Do we actually want to be one country around this? Or do we just want to be right? It’s a big enough problem that I’m willing to put aside parts of my identity to get this done.” Foreign policy, Jones noted, used to unite the country. “I think on some things we should be one country.”

Another questioner referred to studies demonstrating that the higher the level of democratic participation in a given locale, the greater the level of environmental protection and wondered how to create a vibrant local democratic culture. Van Jones described this as “the question we’re going to be answering the rest of our lives: how to make democracy work.” He proceeded to say, “What you describe as a political crisis, I see as a spiritual crisis. If you look at the dynamics we have now, something happened in November 2008 that there is a potential in yourself to be moved by…. And then things got really ugly. And you try to hold that contrast in your mind. We can pretend that’s a political controversy, but there’s something going on that’s a lot deeper than that. I think the country is trying to come to terms with something essential about ourselves.

“We’re the only country in the world that has every race, every class, every gender orientation … and it works. Every day. It’s a miracle every single day in this country. If we can find a way to be a more perfect union with this level of diversity. If we can do the out-of-the-many-one deal right now … ” Isn’t that what we all want? “Yet nobody gets to live in that America without giving up something…. There’s a price … I have to give up being an angry black guy…. When can you give something up? When you have been inspired by something greater. I think that’s what’s underneath…. All of this is a spiritual struggle.

“Progressives love change. But not everyone does: You don’t want to respect what was good for me and my mama and my grandmama?

“If we hold, help and listen to each other and carry each other and support each other, then politics don’t matter.”

Yet, one person wondered, “How can you have change without addressing the consumer-corporate culture so prevalent in the US today?” Parish referred to a new kind of “conscious capitalism” that is emerging and claimed that a high standard of living remains possible for all, but we don’t yet have and haven’t implemented the necessary technologies. He did acknowledge that behavioral changes, life style choices, and “re-localizing” would be necessary.

Jones, however, began by taking this particular bull by the horns: “Your question is a subversive one which goes right to the heart of our challenge: economic growth on an ecologically bounded planet. You get in trouble whenever you touch this thing and you know how I don’t want to get into trouble…. Unlimited growth, the ideology of the cancer cell, can’t be the right answer…. Is green growth possible?” No-growth has “mystical,” but not many other attractions.

Ultimately finessing the growth issue – or pointing to the only way to address it such that a majority of people may be able to hear – Jones addressed once again the need for mutual comprehension and support, arguing that it is important to acknowledge the concern other people may have about progressives, about whether, in addition to their love for the earth and the honeybees, they feel “an unabashed unashamed love of country.

“I think you can [be a progressive and] love your country. I get up every day and try to think of ways to make this country better, of how to extend that idea of liberty and justice for all. And I want my credit as a patriot for that work.”

As a child, Jones wept when they sang “America the beautiful” in school and he remains moved by the words and the concept. “I’m willing to defend her beauty with my life. And I think we should get our credit as patriots for that work … You cannot lead a country you don’t love.”

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $41,000 in the next 7 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.