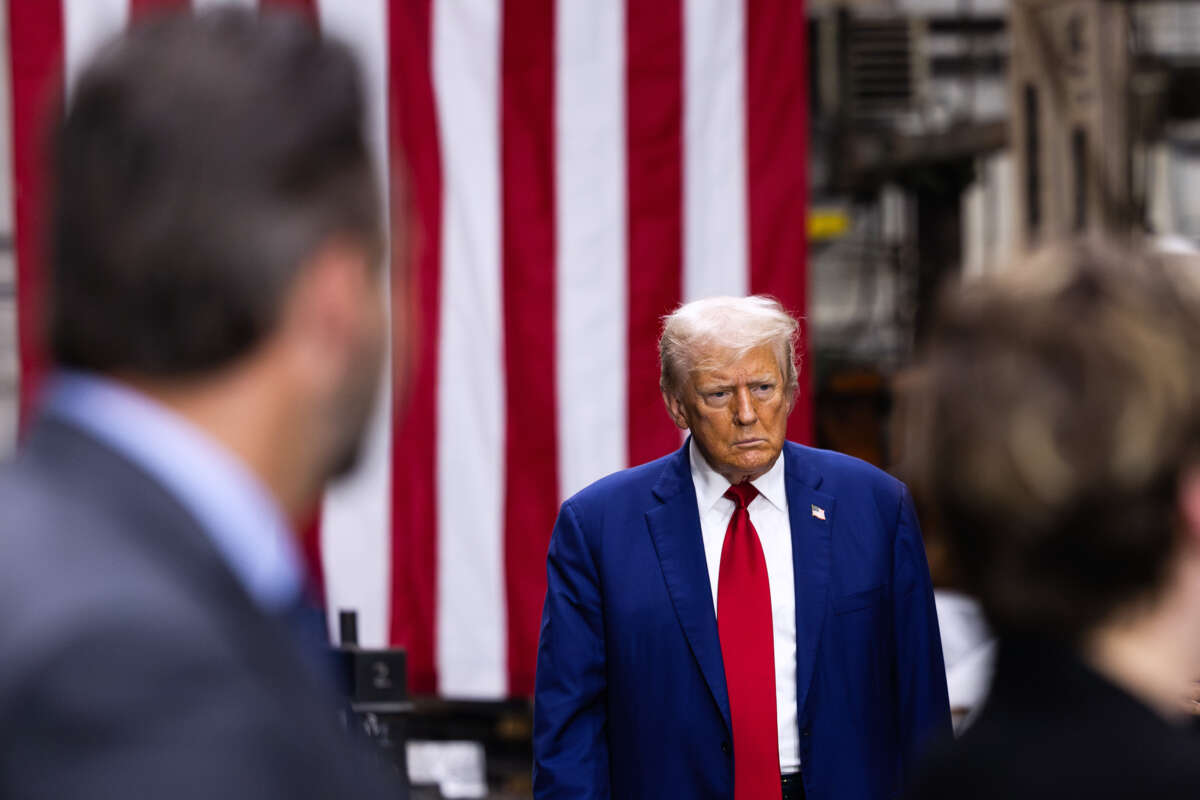

Former President Donald Trump is sometimes depicted as having a less interventionist foreign policy than his Democratic rivals, but this is a myth, argues foreign policy scholar Stephen Zunes. The former president had an extreme militaristic agenda, which he disingenuously pitched as an alternative to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s during the 2016 presidential campaign — an initial source of this myth. During his presidency Trump not only created and bragged about dropping the largest non-nuclear bomb, making a Space Force, and yearning for a military parade, he also became a steadfast supplier of arms to notable human rights violators like Israel, Saudi Arabia and Morocco. In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Zunes discusses Trump’s foreign policy record in Syria, Iran and North Korea. He also forecasts what foreign policy would look like if Trump retakes the presidency or if Vice President Kamala Harris wins in November.

Daniel Falcone: Can you discuss the ways in which the characterization of “Trump as a moderate,” or as someone interested in détente in terms of foreign policy, is simply misleading or false? What was Trump’s actual record of deployment and military buildup and usage during the four years of the “America First” doctrine?

Stephen Zunes: Trump has rejected the neoconservative belligerence of Senators Mitch McConnell, Marco Rubio, and other Republican hawks regarding direct United States military interventionism and putting boots on the ground, but he is still very much a militarist. He dramatically increased military spending during his first term and has promised to do it again with major increases in the already-bloated Pentagon budget, including an extremely costly and dubiously effective missile defense system. He has little interest in real diplomacy of any kind. As with his business dealings, his forays into diplomacy have been largely transactional with lots of threats and bluster.

Despite promises to “bring the troops home,” he increased the numbers of U.S. forces overseas. For example, his “withdrawal” of U.S. forces from northern Syria that were protecting the Kurdish population was in reality a redeployment to other areas of Syria, such as the oil fields, and to Saudi Arabia. He loosened the already lax standards regarding bombing populated areas, leading to tens of thousands of civilian deaths in Taliban-controlled areas of Afghanistan and ISIS-controlled areas of Iraq and Syria.

Trump led the U.S. to the precipice of war with both Iran and North Korea. His impulsiveness, ignorance and bullying could easily trigger a major war, whether that would be his actual intention. His recognition of Morocco and Israel’s illegal annexations of territories seized by force undermined the very foundations of international law and the risks of increased instability and violence. He has openly talked about using nuclear weapons.

Why has Trump been described by some as an “isolationist,” or credited with a near libertarian worldview when it comes to American foreign policy and U.S. militarism?

Throughout the fall 2016 campaign, Trump was able to attack Hillary Clinton from the left over her support for the Iraq War, the Libyan intervention, and other unpopular projections of U.S. military force. Despite having supported the invasion of Iraq and intervention in Libya himself, Trump was largely successful in his disingenuous claims of having opposed these controversial actions and portraying Clinton as a reckless militarist who, as president, would waste American lives and resources on unnecessary, tragic, and seemingly endless overseas entanglements.

Recognizing that more traditional Republican hawks would not support a Democratic candidate regardless, he was able to take advantage of the growing isolationist and anti-interventionist sentiments among conservatives, libertarians, and centrists to consolidate his base. In addition, he was also able to reinforce the unease among progressive Democratic-leaning voters over Clinton’s disastrous pro-interventionist positions, thereby suppressing turnout and encouraging third party support in some key swing states that made the difference in his Electoral College victory.

Trump’s critique of Hillary Clinton’s hawkish foreign policy resonated with millions of Americans, many of whom naively believed he would be less inclined to embroil the country in such wars. White working-class communities in such states as Iowa, Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — which had suffered greatly from sending their children off to fight in them and seen their communities and public infrastructure suffer to pay for it — tilted the balance in those states, which had gone to the less explicitly interventionist Barack Obama when he was the Democratic nominee. Voting turnout among millennials and African Americans, who had also been hurt disproportionately by the Iraq War and subsequent interventions, was much lower than when Obama headed the Democratic ticket. And support for the antiwar Green and Libertarian parties — which more than made up for Trump’s margin of victory in those states — was much higher than in the previous election cycles.

An analysis of voting data demonstrates that areas of the country which experienced the largest number of casualties from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq also experienced the most dramatic shift from Democrat to Republican between the 2008 and 2012 elections and the 2016 election, when the Democrats nominated a supporter of the Iraq War after twice nominating a war opponent.

Trump was able to take advantage of these communities’ losses and anger at the politicians who sent their young people to die in unpopular overseas wars by contrasting himself with both Clinton and his Republican rivals, saying, “Unlike other candidates for the presidency, war and aggression will not be my first instinct. You cannot have a foreign policy without diplomacy. A superpower understands that caution and restraint are signs of strength.”

Trump scored surprisingly well challenging both the neoconservatives and more traditional hawks among his Republican rivals and later against Clinton through his “America First” rhetoric and criticisms of costly and seemingly never-ending overseas wars, particularly the decision to invade Iraq. He claimed, “Our goal is peace and prosperity, not war and destruction,” he attacked Clinton for her “reckless” foreign policy, which he claimed “has blazed the path of destruction in its wake. After losing thousands of lives and spending trillions of dollars, we are in far worse shape in the Middle East than ever, ever before.”

Trump gained support from voters across the political spectrum in a major foreign policy speech in which he portrayed himself as reluctant to use force and Clinton as a dangerous interventionist. In another speech, he asserted that, “Sometimes it seemed like there wasn’t a country in the Middle East that Hillary Clinton didn’t want to invade, intervene in, or topple,” accusing her of being “trigger-happy” and “reckless,” and noting that Clinton’s legacy in Iraq, Libya and Syria “has produced only turmoil and suffering and death. Critiquing Clinton’s distorted economic priorities, he observed, “The price of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will total approximately $6 trillion. We could have rebuilt our country over and [repeatedly].”

It’s been alleged (often by Trump and his supporters) that Vladimir Putin, Benjamin Netanyahu, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong-un, as well as other autocrats, prefer Trump to be the president. Often liberal Democrats take the bait on claims like these and make dangerous statements about these speculations. How have Republicans responded to this assertion?

Republicans are trying to make Trump look like a peacemaker while Democrats are trying to make him look like an appeaser. In some cases, as with Putin, Viktor Orbán, and Netanyahu, Trump really is an appeaser due to his ideological affinity with their rightwing, autocratic, racist, homophobic policies, and their disregard for democracy and international legal norms.

In the case of Jong-un, his flip from threatening war over North Korea’s nuclear program to signing a (vague and nonbinding) joint statement was certainly a positive shift. Some Democrats criticized Trump for agreeing to cancel U.S.-South Korean military exercises, though — while largely defensive in nature — were not necessary and were seen as provocative by the North Koreans, so it was not an unreasonable confidence-building measure. (If President Joe Biden or Obama had done the same thing, Democrats would have defended them, and Republicans would have mercilessly attacked them.) North Korea is a dictatorship, but that doesn’t mean that the U.S. shouldn’t engage in respectful diplomatic negotiations in areas of mutual concern.

What is ignored by both parties is the fact that under both Republican and Democratic administrations the U.S. is the world’s number one arms supplier to dictatorial regimes. Over 57 percent of the world’s autocracies receive U.S. arms transfers. What upsets the Democrats about Trump is that he can be soft on some dictatorships that aren’t closely aligned to the U.S., not that he supports dictators.

Could you comment on the potential foreign policy of Harris? How might she be compared to Biden and Trump in this area?

A Harris presidency will likely be like an Obama presidency. She will be much less hawkish than Biden and more respectful of human rights and international law, but unlikely to change the basic thrust of U.S. foreign policy. She would help rebuild U.S. credibility that has been lost initially during the Trump presidency and through Biden’s strident support for Israel, but is unlikely to question the hegemonic thrust of U.S. foreign policy. Her foreign policy chief Philip Gordon is skeptical of the use of military force, is more willing to be critical of Israel, and is a moderate on Iran. At the same time, he has supported closer relations with Saudi Arabia, has referred to the Israeli-occupied Golan region of Syria as part of “northern Israel,” and categorically rules out ending military aid to Netanyahu despite ongoing largescale war crimes.

It is extremely difficult for a sitting vice president to be elected president. Only four have tried since the early 19th century, and three of them lost. They cannot break with their president on major issues, particularly dealing with foreign policy, and they must find a balance between asserting their own agenda and not appearing disloyal and sowing divisions within the party by openly contradicting their president’s positions. This was Hubert Humphrey’s dilemma in 1968, and it resulted in his narrow defeat to Richard Nixon. For example, Harris can emphasize her concerns about civilian casualties in Gaza but cannot contradict President Biden on military aid to Netanyahu.

Truthout Is Preparing to Meet Trump’s Agenda With Resistance at Every Turn

Dear Truthout Community,

If you feel rage, despondency, confusion and deep fear today, you are not alone. We’re feeling it too. We are heartsick. Facing down Trump’s fascist agenda, we are desperately worried about the most vulnerable people among us, including our loved ones and everyone in the Truthout community, and our minds are racing a million miles a minute to try to map out all that needs to be done.

We must give ourselves space to grieve and feel our fear, feel our rage, and keep in the forefront of our mind the stark truth that millions of real human lives are on the line. And simultaneously, we’ve got to get to work, take stock of our resources, and prepare to throw ourselves full force into the movement.

Journalism is a linchpin of that movement. Even as we are reeling, we’re summoning up all the energy we can to face down what’s coming, because we know that one of the sharpest weapons against fascism is publishing the truth.

There are many terrifying planks to the Trump agenda, and we plan to devote ourselves to reporting thoroughly on each one and, crucially, covering the movements resisting them. We also recognize that Trump is a dire threat to journalism itself, and that we must take this seriously from the outset.

After the election, the four of us sat down to have some hard but necessary conversations about Truthout under a Trump presidency. How would we defend our publication from an avalanche of far right lawsuits that seek to bankrupt us? How would we keep our reporters safe if they need to cover outbreaks of political violence, or if they are targeted by authorities? How will we urgently produce the practical analysis, tools and movement coverage that you need right now — breaking through our normal routines to meet a terrifying moment in ways that best serve you?

It will be a tough, scary four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. We need to deliver news, strategy, liberatory ideas, tools and movement-sparking solutions with a force that we never have had to before. And at the same time, we desperately need to protect our ability to do so.

We know this is such a painful moment and donations may understandably be the last thing on your mind. But we must ask for your support, which is needed in a new and urgent way.

We promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation and vitriol and hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please dig deep if you can, but a donation of any amount will be a truly meaningful and tangible action in this cataclysmic historical moment. We’re presently working to find 1500 new monthly donors to Truthout before the end of the year.

We’re with you. Let’s do all we can to move forward together.

With love, rage, and solidarity,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy