Neil Steinberg of the Chicago-Sun Times writes, “Rory Fanning’s odyssey is more than a walk across America. It is a gripping story of one young man’s intellectual journey from eager soldier to skeptical radical, a look at not only the physical immenseness of the country, its small towns and highways, but into the enormity of its past, the hidden sins and unredeemed failings of the United States. The reader is there along with Rory, walking every step, as challenging and rewarding an experience for us as it was for him.”

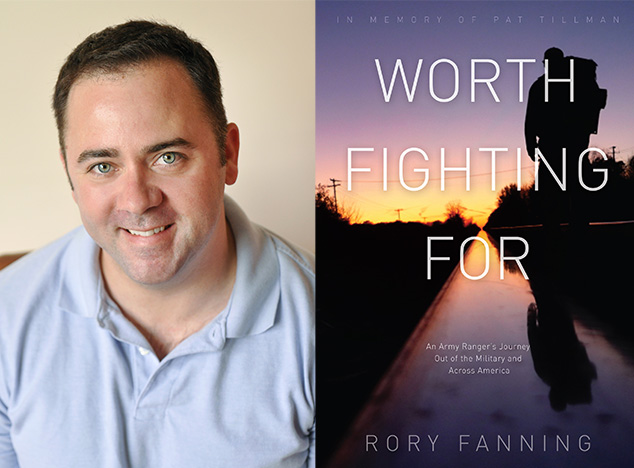

The following is an excerpt from Chapter Eight, “New Mexico” of Worth Fighting For: An Army Ranger’s Journey Out of the Military and Across America:

I was on a never-ending ribbon of road, walking above a calm ocean of moonlit dust, as I entered my favorite state. There were no flashing red radio towers, tall white windmills, or glowing orange streetlights. It was dark.

My sophomore year in high school, my dad took me out of school for a two-week road trip. He was looking for work in California. My teachers weren’t pleased. I was excited but anxious about my dad’s rejection of routine and order and happily agreed to escape from school. We slept in the car mostly. One of those nights was under a full moon, surrounded by distant New Mexican plateaus on a quiet side road in the dessert. I grew restless trying to sleep in the passenger seat that night and rolled out of the car onto the side of the road as soon as I heard my dad snoring. I used a coat as my pillow and fell asleep on the hard, pebble-strewn ground, staring at the moon. I fell in love with New Mexico that night.

New Mexico, my favorite secret spot, was also the military’s favorite secret spot.

In the military we jumped into the White Sands military base – where the geography most resembled Afghanistan – on a clear November night. They strapped a giant rocket launcher to me. The weight of the long green ceramic pipe pulled me head-first out of the plane. The parachute opened and sliced a two-inch gap in my chin. I landed and chin skin flapped like an unmasted sail in the warm, dark desert wind. I hardly noticed the blood pouring from my face because I was so happy to be back in New Mexico, with a few moments to reflect and briefly escape the military’s attempt to lobotomize me. My squad leader – in Afghanistan I would later see him running around lost in the sound of rocket fire, doing everything but leading – barked when he saw me, “Hey, John Wayne, buckle your fucking chin strap. I don’t care how much you’re bleeding.” I liked the solitude of New Mexico.

A supersonic aircraft rattled the rocks on the road as I walked with my pack alone through my tenth state that night. The government had chosen Los Alamos, which was only a few miles from me, as the site for the Manhattan project. How did the place where I could see myself the clearest in also become the birthplace of the atomic bomb? New Mexico, my favorite secret spot, was also the military’s favorite secret spot. I walked until almost one in the morning, hoping to find cell reception and trying to conserve water.

I felt like I was chasing chickens as a frantic wind blew coats, bags, hats, and my tent across a cow pasture while I attempted to pack the next morning. Soon after, a fire-hose stream of air kept me fighting to maintain a pace of less than a mile and a half per hour. It was the most challenging wind of the trip. I visualized myself as a cheese wire, cutting thin and sharp through the invisible pressure. When that grew dull I chased my hat brim as if it were a plastic rabbit at the dog track. The next time I walk across the country I’ll start at the Pacific and walk with the wind, I thought. For hours the wind continued to yell “No!” until finally, around six, the great Western throat grew hoarse and the sun, the stirred dust, and the metallic clouds calmed into a well-beaten-bruise color in the sky. Any other state, and my staff and I would have been irritated by the treatment. I saw that day, however, as a rite of passage into New Mexico. I thought that I would endure months like that to earn New Mexico’s respect.

TATUM, NM | Mile 1,757

Population 683 | Est. 1909

A wind advisory with forty-mile-an-hour gusts turned Tatum and Highway 380 into a blurry and indiscernible Russell Chatham landscape painting. I saw a man with rust-colored hair and ripped jeans sitting on a pallet under an underpass. He stared at the ground and didn’t notice I was walking toward him. He looked up and I was standing over him. I handed him the hundred dollars the sheriff had given me. I left without words being exchanged.

I was seventy-five service-free miles from the nearest town: no gas stations or restaurants until Roswell. Water was the bulk of the challenge. I added seven pounds of water weight to my pack. The extra weight, heavy winds, and length of time until my next refueling kept me in Tatum waiting for better wind. Kevin Tillman called me that night. It had been years since we’d last talked. He said he was inspired by what I was doing; he said Pat would be proud. The call rekindled a friendship that has lasted to this day. Kevin is one of the most genuine people I know.

He is also one of the most courageous people I know. He spoke truth to power before Congress when he demanded answers and accountability of those who covered up Pat’s death. Before Congress and the nation, he eloquently said:

In the days leading up to Pat’s memorial service, media accounts based on information provided by the Army and the White House were wreathed in a patriotic glow and became more dramatic in tone. A terrible tragedy that might have further undermined support for the war in Iraq was transformed into an inspirational message that served instead to support the nation’s foreign policy wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. To further exploit Pat’s death, he was awarded the Silver Star for valor. . . . It’s a bit disingenuous to think that the administration did not know about what was going on, something so politically sensitive.

You don’t hear such candor on TV very often, especially from someone testifying before Congress. There was no double talk or tiptoeing around the truth during Kevin’s testimony. You certainly didn’t hear the same candor from Donald Rumsfeld or the generals called to testify about the cover-up. Kevin said it like it was.

“You can’t change the world until the mortgage is paid.”

I was in Montana at a bar on May 30, 2004, when I heard that Pat’s death had been a friendly-fire incident. ESPN had nearly twenty-four-hour coverage of the story. An angry but determined feeling settled into me that day. I soon challenged myself to figure out what other lies I was being fed. I vowed not to let the news of the cover-up poison me with cynicism and apathy. I couldn’t. The military and the government had taken enough energy from me. They wouldn’t take any more.

So I set out to really learn. But that’s easier said than done. It’s hard to say you’re going to figure out how the system works and do your best to take ownership over this country and expose injustices when you have to worry about paying the bills. Like Caleb, the little boy behind the register in Paris, Texas, said, “You can’t change the world until the mortgage is paid.”

Many of my family and friends rejected the way the Tillman family confronted the military. Accidents happened, they said. The powers that be were doing their best. The fact is, the system worked for most of my family and friends. They lived in good homes. They believed they had earned all of what they had and that those who hadn’t needed to stop being lazy and blaming others for their dependence on the government – that, somehow, those who had none of the military, political or economic power were the ones responsible for all the problems. Questioning my family and friends’ beliefs meant risking my relationship with them. They helped me learn how to stand up for what I believed in. But Pat and Kevin made figuring out the truth and holding the powers that be accountable feel necessary and important – even if the price was high.

Tatum is a small town. Noise pollution on Main Street amounts to the constant roll of wind chimes. There are three restaurants. One is in a gas station; the other is closed on both Sunday and Saturday. I ate at the third, the Steak House Cafe, three times. Twice someone paid for my meal without reading my pack or mentioning the walk. The townspeople knew who I was and what I was doing less than twelve hours after I arrived.

Metal art is the main tourist attraction in Tatum. From street to restaurant signs, thin metal silhouettes of Indians, aliens, soldiers, and coyotes ornament Tatum’s frontage. There are two motels. One is condemned and the other is the Sands, where I stayed, which embraces a seventies-era motif. Its lack of pretension gives it a relaxing energy. The manager is Carla, who lives at the motel. She had managed it for ten years. She told me that she and her late husband had a handshake agreement with the man who held the note on the property. They were making payments to one day buy the Sands. The note holder decided to sell to a third party instead, and Carla was heartbroken. With tears rolling down her cheeks, she said, “This place is my ministry. I spread God’s word here. I will be so sad to leave it.” Carla donated the cost of the room and did my laundry without charge. The next day, when we chatted, the tears had stopped, and she seemed optimistic about the future. She had plans to move into a mobile home with her new husband and hoped to continue her ministry in a new way. She said, “I want to hand out grocery gift certificates to people I can sense need them.”

Loaded with two boxes of cookies-and-cream Pop-Tarts, beef jerky, four tuna packets, eight quarts of water, and B vitamins, I left Tatum at noon for the seventy-three-mile town- and service-free walk to Roswell. The first six miles were slow. Then I noticed a wind hitting my back at a forty-five-degree angle, a rare and unfamiliar feeling walking west. It lasted an hour, during which I covered almost five miles in spite of my loaded pack. This propelled me into the night. The mile markers began to fall off like tin cans at pistol range. I had my head down and I was feeling good. Around ten-thirty that night I thought I would make a run at fifty. My previous best was 38.1.

I thought fifty was possible after I learned that the 101st Airborne Division had walked 150 miles in three days while training for World War II. Eisenhower – who as president would later go on to overthrow the democratically elected presidents of three sovereign countries – created the controversial and dangerous parachute division to catch the Germans off guard behind their lines. He knew the men of the 101st could get scattered and be forced to survive and walk on their own for days. Each “Screaming Eagle” hopeful had to walk 150 miles in seventy-two hours as part of the training. If they could do 150 in three days, I could try 50.

Highway 380 grew dark and quiet. Around two-thirty in the morning, popped semi tires began to look like squirming eels, road signs turned to axe murderers, and a lone mid-eighties white Buick abandoned on the side of the road was surely filled with drug dealers who would rob me of my dirty laundry. At three-thirty, after thirteen and a half hours of constant walking, I was suspiciously blissful. I had not seen a headlight in hours. A hazy moon was above me, New Mexico desert to my right and left. I was walking centered over the yellow-striped median, listening to Radiohead’s “How to Disappear Completely.” It seemed to have been written for me at that moment. The time before sunrise was the most difficult. My body felt old and broken. My forty-five-pound pack felt like a cancerous growth. I was paranoid from a lack of sleep. I was talking to myself and didn’t want to walk ever again. The sun rose and I found a new burst of energy – only six miles to fifty. Those six miles took three hours. Finally, at ten AM, I crossed the fifty-mile marker.

There are As to be made on tests, trophies to be won in sports, and well-earned paychecks to be received in the workforce. Walking fifty miles with a forty-five to fifty-five-pound pack on my back was an accolade-free accomplishment that meant as much to me as all of the above combined. At ten-thirty I climbed a fence and took a nap. The lactic acid that had pooled in my muscles made getting comfortable impossible. After a little stretching I fell asleep for forty-five minutes. I woke to thirty brown quarter horses staring at me. I stood up and they scattered. I slept the rest of the day and into the next morning. I was twenty-three miles from Roswell.

I climbed atop a plateau I had been staring at for twenty miles and saw white billows in the sky that were not clouds. It was my first glimpse of the snow-covered Rocky Mountains. Helping celebrate the milestone, scores of antelope jogged within thirty yards of me as I made my way down towards the city limits of Roswell, still worn down from the previous day’s walk.

Help us Prepare for Trump’s Day One

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy