Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Jose Guerrero was a true people’s artist.

The Mexican-American muralist and printmaker died in Chicago – his home for more than half a century – this month at age 77.

But his work lives on. And the outpouring of sentiment after his death shows not only how beloved Guerrero was, but also the power that populist, political, collective-minded work like his still has to inspire, uplift, provoke and unite.

An art theorist would call Guerrero “self-taught,” but that label would do an injustice to the diverse community of Chicago artists he was part of, people who see art as a tool for social change and a language of empowerment. Though he had no formal art education, Guerrero learned from the acclaimed local artists he worked alongside, and from the students from all walks of life whom he taught himself.

Guerrero celebrated people who worked hard for low pay, unemployed people, immigrants, dissidents, campesinos and mothers.

“He would always say there is no art for art’s sake,” said Hector Duarte, a well-known Mexican artist in Chicago. For Duarte’s “Butterfly Project,” artists and students decorated butterflies that Duarte incorporated into a mural in his hometown in Michoacan as a symbol of migration and connection. Guerrero’s butterfly bore a flag for striking workers and the slogan “Despierta Pueblo Sufrido” (“Awake Suffering People”).

“He always had the approach of building a better society, of waking people up, of helping people think in a new way,” Duarte added. “But he also had a sense of humor. Sometimes art is too serious. He brought humor.”

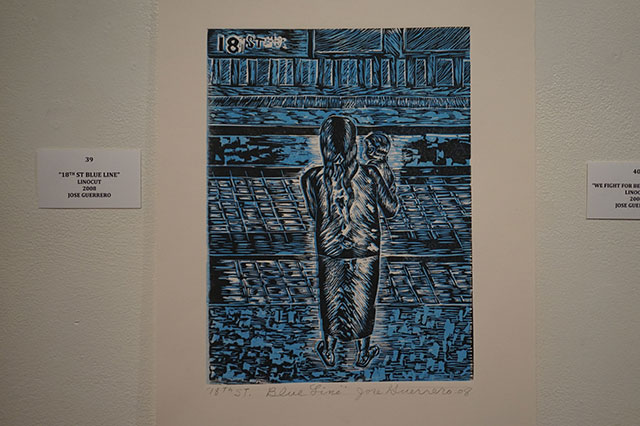

“18th Street Blue Line,” 2008 linocut print by Jose Guerrero. (Photo: J Burger)

“18th Street Blue Line,” 2008 linocut print by Jose Guerrero. (Photo: J Burger)

In murals, drawings and linoleum prints, Guerrero celebrated regular people, people who worked hard for low pay, unemployed people, immigrants, dissidents, campesinos, mothers, street vendors, bar flies, children and protesters.

Guerrero was a workingman himself. Born in San Antonio, he moved to Chicago in 1964 and got a job in the Sunbeam factory making appliances. He also drew cartoons for a rank-and-file newspaper called People Get Ready, distributed in a handful of factories, as artist John Pitman Weber described in a recent obituary.

In the mid-1970s, Weber and Guerrero created the murals that blanket the United Electrical Workers (UE) union hall on Chicago’s historic union row, Ashland Avenue. In keeping with UE’s status as a progressive, independent union, the defiant murals show powerful and dignified working men and women, in the style of Mexican great Diego Rivera, and mockingly depict the greedy bosses and officers who tried to keep them down.

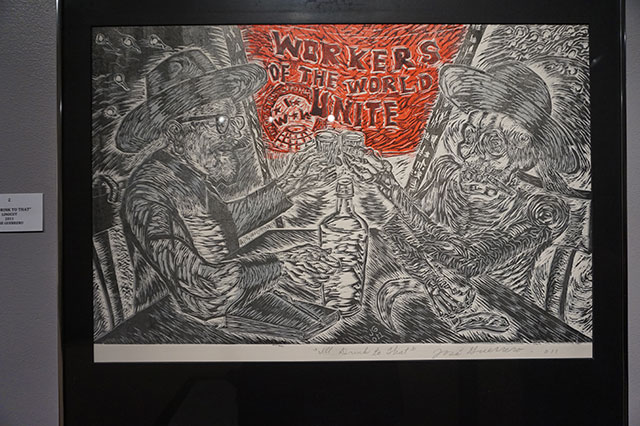

This Jose Guerrero print shows his mentor, artist Carlos Cortez, toasting “Death.” (Photo: J Burger)

This Jose Guerrero print shows his mentor, artist Carlos Cortez, toasting “Death.” (Photo: J Burger)

“The UE could barely keep its lights on, so the union paid only for our materials,” wrote Weber, an internationally known muralist and founder of the Chicago Public Art Group. “But we were both happy to have the rare opportunity to practice mural composition on the aging plaster walls of a late 19th-century building. We used a quote from Frederick Douglass for the mural’s title: ‘Without struggle there is no progress.’ Douglass’s words fit our intentions – to use art as a tool to shape a better world.”

Guerrero worked with Weber and other artists on various murals in neighborhoods including Pilsen, Humboldt Park and Logan Square – hardscrabble barrios home to Mexican immigrants, Chicanos like himself, Puerto Ricans and African Americans. This was a time when national civil rights, Latin American solidarity and antiwar movements were roiling the country and also playing out on local levels in Chicago neighborhoods.

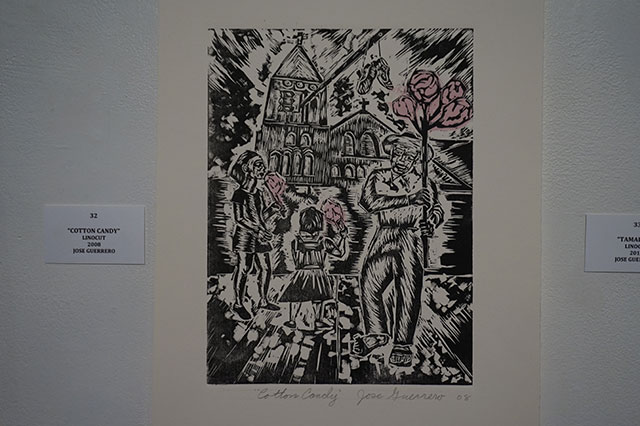

“Cotton Candy,” 2008 linocut print by Jose Guerrero. (Photo: J Burger)

“Cotton Candy,” 2008 linocut print by Jose Guerrero. (Photo: J Burger)

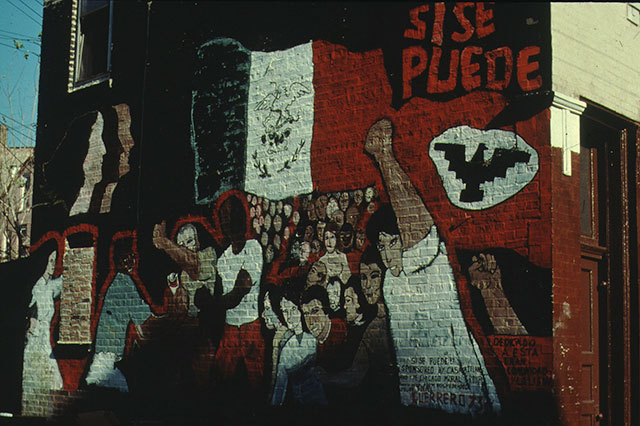

The muralism movement that Guerrero was part of played a major role in these intertwined struggles. His first mural, near Casa Aztlan – a onetime settlement house later home to numerous artists, community groups and the Brown Berets – was an homage to the United Farm Workers.

“A lot of people think about the end result with art. To him, it was the process. He talked a lot about looking and thinking.”

One mural Guerrero participated in, now mostly chipped and faded away, adorns a crumbling railroad viaduct on the western edge of Pilsen. “Provoked by the prospective election of right-wing, pro-nuke, dictator-coddling Ronald Reagan in 1980, Prevent World War III was a spontaneous, collective action taken by a dozen or so socially conscious artists – a true who’s who of pre-eminent muralists,” wrote art journalist Jeff Huebner of the mural, which was organized by Weber.

Another mural Guerrero worked on, “Smash Plan 21,” referred to a highly controversial urban renewal plan seen as a roadmap for gentrifying Pilsen and the surrounding area.

Jose Guerrero worked with John Pitman Weber painting iconic murals on Chicago’s UE union hall. Mural by Jose Guerrero and John Pitman Weber. (Photo: J. Burger)

Jose Guerrero worked with John Pitman Weber painting iconic murals on Chicago’s UE union hall. Mural by Jose Guerrero and John Pitman Weber. (Photo: J. Burger)

Gentrification was a common theme of Guerrero’s murals, especially in Pilsen, which is widely seen as a case study of the phenomenon. Over the course of several decades, Guerrero worked on Pilsen murals that showed people proclaiming their land and their homes were not for sale, sometimes evoking epic land struggles in Mexico, the homeland of many Pilsen residents.

The murals served to educate people about gentrification and other political issues, and also to stake a claim, to announce the neighborhood’s identity and the community’s devotion to remain there.

In 1980, Guerrero founded Pilsen Mural Tours. The thriving grassroots enterprise was administered largely by Margaret, Guerrero’s wife of 52 years. College, high school and tour groups from around the Midwest and from other countries flocked to Pilsen for the mural tours, many returning year after year.

Jose Guerrero and John Pitman Weber’s murals inside Chicago’s UE union hall show working people battling racist forces. (Photo: J. Burger)

Jose Guerrero and John Pitman Weber’s murals inside Chicago’s UE union hall show working people battling racist forces. (Photo: J. Burger)

Guerrero was unwavering and radical in his left-wing politics and his disdain for the ruling class. But the mural tours were just one example of how he warmly welcomed people of all backgrounds and races to Pilsen without ever a trace of anger or stridency.

He had a soft-spoken, steadfast style of resistance, a sly sense of humor and irrepressible optimism that often seemed the ultimate way to triumph over the forces of injustice and degradation. Many participants on the mural tours have described how Guerrero’s low-key but passionate approach helped educate people about social and political struggles, and helped them feel solidarity with communities they had never met.

Some prints featured raised fists, rippling muscles, determined faces, brutal scenes of injustice and militant defiance.

While Guerrero may be most closely associated with murals, his most prolific work in recent years was in printmaking – a classic medium for political and populist art in Mexico and the United Stares. Guerrero learned printmaking largely from Carlos Cortez, a prominent Mexican-German Chicago artist, poet and labor activist with a gentle bearing and a sly twinkle in his eye similar to Guerrero’s.

Guerrero was one of the founders of the Taller Grafico Mexicano, or Mexican Print Workshop, later posthumously renamed in honor of Cortez. Housed in the ground floor of an historic, once-grand Bohemian building on Pilsen’s main drag of 18th Street, the workshop became an artistic hub for Mexican and Mexican-American artists, likely mirroring the culture of the Bohemian immigrants who founded the neighborhood a century earlier.

Jose Guerrero participated with other prominent muralists on “Prevent World War III” in Pilsen. (Courtesy of Chicago Public Art Group)

Jose Guerrero participated with other prominent muralists on “Prevent World War III” in Pilsen. (Courtesy of Chicago Public Art Group)

Guerrero spent long hours making linoleum prints on the heavy, hand-cranked press that sat in the workshop. Margaret, who celebrated her own Appalachian artistic culture through quilting, also took up printmaking. At the workshop, Guerrero taught low-cost or free classes to kids and adults – from local families who spoke little English to college students from around the country.

Kim Grove, one of the relatively few white residents of Pilsen since the early 1990s, credits Guerrero with her artistic and political awakening. Grove met him at the workshop during an open studios event and was soon, along with her good friend Kate Perryman, joining Guerrero’s freewheeling printmaking classes. Under his tutelage she became serious about printmaking, and also learned about political struggles from Mexico to her own backyard in Pilsen.

“You think of students as being young people, but he brought in everyone. He loved bringing together people of all different generations,” said Grove, smiling fondly at the memory of working long hours to Guerrero’s favorite music, including romantic Mexican ballads and “The Christmas Song.” “A lot of people think about the end result with art. To him, it was the process. He talked a lot about looking and thinking. Chatting and having a beer on a Sunday in the studio, taking time,” she said.

Grove and Perryman, a trained artist, helped Guerrero assemble an ambitious print portfolio project in which artists ranging from beginners to luminaries like Duarte and Weber contributed prints and received a full set from the other participants. The theme was “From Where We Stand, There Are No Borders.” Guerrero’s contribution depicted a 2001 event in which a boat load of Dominican migrants survived being lost at sea thanks to the breast milk of one of the women.

The printmaking portfolio process, wherein people help each other complete their prints and share the results, was symbolic of Guerrero’s approach, according to Perryman.

“Printmaking is a very democratic medium,” she said. “You can make a lot of each one, and you have to work together. Like murals, they’re not in a white cube that only the elite can see; they’re for everyone. Those are mediums that he chose in keeping with his beliefs.”

Jose Guerrero’s first mural, in the Pilsen neighborhood, celebrated the United Farm Workers union. (Courtesy of Chicago Public Art Group)

Jose Guerrero’s first mural, in the Pilsen neighborhood, celebrated the United Farm Workers union. (Courtesy of Chicago Public Art Group)

Guerrero’s prints typically feature downtrodden and regular people in a way both radical and joyful.

Some prints featured raised fists, rippling muscles, determined faces, brutal scenes of injustice and militant defiance. Others show the simple joy and dignity of life in Pilsen and communities like it: the pink blooms of a street vendor’s cotton candy in an otherwise black and white streetscape; peaceful blue ink bathing a mother holding a child, a long braid down her back, on the platform of Pilsen’s 18th Street blue line station.

Guerrero’s prints were long very popular, and seem to have become even more so since his death, with people clamoring to buy them as Margaret and friends begin the painful process of clearing out the workshop. Everyone has their own reasons that particular images speak to them. But it seems likely that the appeal of Guerrero’s work lies partly in what it represents visually and symbolically – a swirling, proud, hopeful view of the world, embodying childlike wonder and humor even in the face of age-old injustice.

One Guerrero prints shows his mentor Carlos Cortez in a toast with Death – one of the skeletal calaveras prominent in Mexican art. Behind their clinking tequila glasses is a red Industrial Workers of the World banner saying, “Workers of the World Unite.”

Calaveras are often used in a political context, including by the famous Mexican “people’s printmaker” Jose Guadalupe Posada. Among other things, calaveras represent equality – the ultimate fate that all people face regardless of their wealth and power on earth.

Guerrero told Margaret he wanted no ceremony or pomp and circumstance after his death. Like Carlos Cortez toasting Death, perhaps he saw his own passing as just part of the cycle that makes us all equals, brothers and sisters in the end.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.