The Royal Road from Wolfe Video on Vimeo.

Donald Trump’s continued leveraging of US xenophobia as a presidential campaign strategy has relied heavily on a particular strain of Mexiphobia, which continues to bring new and hateful manifestations as the days go by.

The root origins of this atmosphere of Anglo-anxiety lie in a century-and-a-half of official government and societal amnesia around the true history of our shared physical landscape with the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos) — and the reality that Trump’signominious wall might instead be placed along a much farther Northern border (like up near Oregon for instance).

The Royal Road clip: California history from Wolfe Video on Vimeo.

As a filmmaker I have always been interested in exploring lesser-known or less-spoken about historical topics. It has always seemed amazing to me the way that the Spanish colonization of California and the Mexican-American War are taught in US schools — mainly fleetingly and in such a way as to obscure the painful truths of conquest (first, theconquest of the Native Americans by Father Junipero Serra and the Spanish Missionaries, and then the conquest of the Republic of Mexico by the United States under the direction of President James K. Polk).

My new film, The Royal Road is very unconventional in that it consists entirely of 16 millimeter durational urban landscape shots across the state of California (San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz) accompanied by voiceover as I reflect on a variety of topics including Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, butch lesbian identity and unavailable women — yes, it is a unique combination and not without a fair amount of dry humor, I might add.

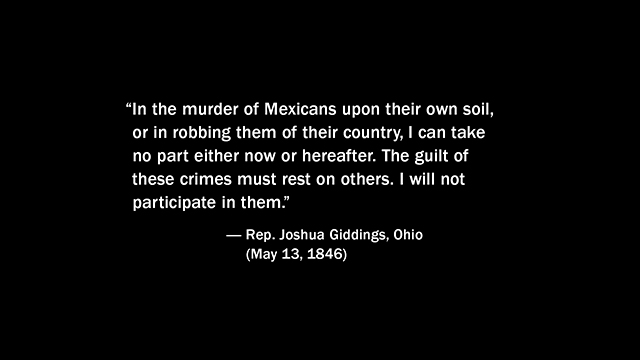

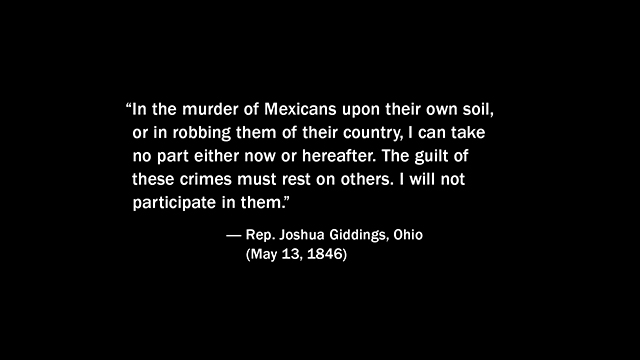

The main historical exploration in The Royal Road is around the geographic reality of theMexican cession after the end of the Mexican-American War and my exploration of the war as essentially unjust. I also observe that there had been many US resistors of the war including then Congressman Abraham Lincoln and Ohio Congressman Joshua Giddings who proclaimed chillingly in 1846:

Joshua Giddings quote production still from The Royal Road. (Photo: Jenni Olson Production)

Joshua Giddings quote production still from The Royal Road. (Photo: Jenni Olson Production)

“In the murder of Mexicans upon their own soil, or in robbing them of their country, I can take no part either now or hereafter. The guilt of these crimes must rest on others. I will not participate in them.”

As a white person living in California, one can’t help but be aware of our state’s unique heritage — Latino, Spanish, Native American. My film makes an effort at exploring a tiny bit of this history using our famous thoroughfare of El Camino Real as a structuring device. El Camino Real still bears the name given to it by the Spanish conquerors of the Native Americans, who were then conquered in their turn (when Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821, which was then followed by the United States forcibly taking theterritory following the Mexican-American War in 1848).

Making this history visible is more important than ever in the US today. I hope my film can play a small role in moving things forward. As I say in the film:

“It’s not difficult to understand why the United States as a country would want to forget about the Mexican-American War. In the ongoing climate of anti-Mexican sentiment, it’s easy to see the importance of remembering.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.