Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Companies have been “blackening up” on Twitter lately. Performing blackness is normalized as good marketing. However, the appropriation and theft of black culture by outsiders is rooted in the tradition of minstrelsy.

It’s hard to recall a time historically in the United States when black people have not been giving back to society, although media narratives portraying black people as childlike and irresponsible are never in short supply. Still, black people have always given without pause to the cause, service and culture that is the United States. We have done this through force, through love, resentment and more. Black tongues have developed the taste of the United States; black feet designed the ways we dance, and black mouths consistently shape the way the nation talks.

It’s amazing that a country that has always held black people as second-class has also always sought out significant portions of its cultural identity from those it oppresses. As white capitalism developed riding on the backs of black folks, it has always managed to look down to see what we were wearing and hear what we are saying. Blackness is not just beneficial for fitting in; it’s profitable and marketers have known this for ages. The origins of marketing blackness have specific roots in blackface performances and minstrelsy.

Today is no different from the past in this sense. Black culture is dismissed as being “ghetto,” “ratchet” and incongruent to civility even as it is recycled for white audiences. The pattern is frustrating for many blacks, flattering to some and goes seemingly unnoticed by others. It’s important to remember appropriation is not exclusive to black communities. For instance, native people in the United States are battling a football team that doesn’t want to change its name and address its racist appropriation and insensitivity. And we just concluded Halloween season where people freely fall victim to invitations to co-opt an identity.

Marketing and capitalism are intertwined in many places where this happens. The appropriation of black culture is a frequent topic of discussion and everyone does it, not just white people. It’s a regular sight to see other people of color and non-white people talk about the regularity of cultural theft from blacks while engaging in it themselves. However, it’s white appropriation that perfected the thievery that is rooted in minstrelsy.

Thomas D. Rice, also known as “Daddy Rice,” was the founding father of modern minstrelsy. He was the brick and mortar to much more than what we have come to know as a minstrel show. It was in his travels as a performer that he overheard a black stablehand named Jim Crow singing a song he would steal for his creation of arguably the most famous minstrel show ever. His performance centered on the appropriation of that black vernacular, movement and musical performance. The Jim Crow performance would later dub the apartheid system used throughout the United States to strategically disenfranchise and segregate blacks. It’s important to note that these minstrel show performances of blackness were reimagined and (mis)interpreted by a white gaze. Therefore, it comes with its own racism, misuse and exaggeration. In keeping with the historical pattern, those who appropriate from blacks today are often racist, incorrectly assert their usage and exaggerate themselves. What’s particularly fascinating is watching companies perform blackness as a marketing ploy.

A recent example of the trend has taken place on Twitter. Companies, like many social media users themselves, have realized that Facebook is dying, particularly among teenagers. This group is significant for advertisers looking to attract young people by making their product look cool. So, while Facebook awaits a seemingly inevitable coup de grace, Twitter is figuring out how to further monetize its users. The answer is simple – advertising – and companies are ready with their digital shoe polish.

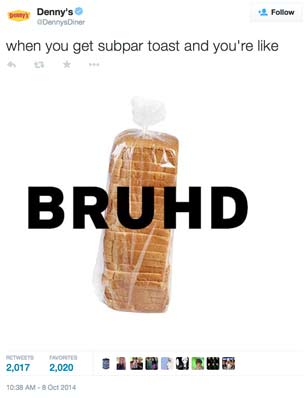

The first company blackening up for retweets was Denny’s, with their infamous Twitter account. They have captured tens of thousands of retweets by capitalizing largely on black internet culture and jargon. “Pancakes or nah,” “hashbrowns on fleek,” and “BRUH[D]” are all tweets that originated from Black Twitter’s slang. To be more specific: These things were already being said by black folks, reached virality via black Vine and Twitter users, and now are being appropriated for advertising. Companies like Charmin, IHOP, Burger King and Taco Bell have all joined in – which will bring about another tradition; black people will abandon a cultural trend because everyone else’s overuse watered it down. Language is fluid and we should not expect it to stay within one community, but the way black culture is consistently appropriated by everyone for profit is unique. The performance sells and can be utilized by any entity.

Even within the black community, the performance of black womanhood by black men, queerness by straight blacks, and transgender identity by cisgendered blacks is regularly offensive. And keep in mind that some minstrel shows were black people dressed as white people portraying blacks. Anyone is good enough to borrow blackness, but blackness itself is undesirable. We look at relics of racist caricatures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben in museums as things of the past, while companies mimic blackness in the exact same tradition.

A very relevant example of this market pattern from the last century is that of early jazz recordings. The jazz genre, like most American genres, was created by black people. However, the first commercial recording of jazz music was of an all white band, the Original Dixie Land Jazz Band. Although they were playing black music largely frowned on at the time and had gotten their style from black artists, marketers knew a white band could reach a commercial success black artists couldn’t. After their commercial success, the band’s leader, Nick LaRocca, would later falsely claim they “invented jazz,” just as Elvis perfected rock music, and so on. It’s not enough to appropriate; along with appropriation often comes insult and blacks are told they are not fit to profit within the markets we originate.

The consistent historical exploitation looks like this: A black brain creates; the black community participates – and everyone else takes it away. It’s the blues; it’s jazz; it’s fashion; it’s everything. Part of the labor of blackness is not having anything that is really your own. Even if the culture is ours, many black people constantly create and reinvent themselves to define their blackness. It’s crucial for black people whom the world incorrectly views as being without culture, while simultaneously snagging whatever they can from that non-culture.

At this point, the appropriation of blackness on social media should come to be expected. We need to recognize cultural labor dependency on black people as a staple of the US economy. If the country ever makes it far enough to admit this, maybe it could consider compensation. I’m not the first to say any of this and I won’t be the last. When you’re black, you’re never the last to say anything. Someone will hear you and repeat it.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.