This past July, students from Northwestern University’s Medill Justice Project visited the infamous Louisiana State Prison known as Angola. While there, students landed an impromptu interview with Warden Burl Cain, where they asked him about an inmate at Angola named Kenny ‘Zulu’ Whitmore, who has now been in solitary confinement for 28 consecutive years. This important interview was cited afterwards by Time Magazine in an article examining the impact of solitary confinement on prisoners’ health.

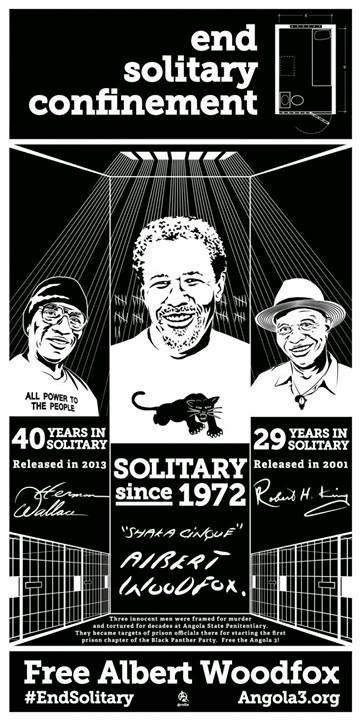

Zulu Whitmore is a member of the Angola Prison chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP) that was first started in the early 1970s by Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox of the Angola 3. In reply to the students’ question about Whitmore, Cain cited his affiliation with the Angola BPP and expressed concern that Whitmore could spread his beliefs in the prison, sparking violence among inmates. “The Black Panther Party advocates violence and racism—I’m not going to let anybody walk around advocating violence and racism,” Cain said. At the time of publication, Whitmore remains in solitary confinement.

Burl Cain’s characterization of the BPP as “advocating violence and racism” is reminiscent of a deposition he gave on October 22, 2008, following Albert Woodfox’s second overturned conviction, where Cain cited Woodfox’s affiliation with the BPP as a primary reason for not removing him from solitary confinement. Asked what gave him “such concern” about Woodfox, Cain stated: “He wants to demonstrate. He wants to organize. He wants to be defiant.” Cain then stated that even if Woodfox were innocent of the murder, he would want to keep him in solitary, because “I still know he has a propensity for violence…he is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates.”

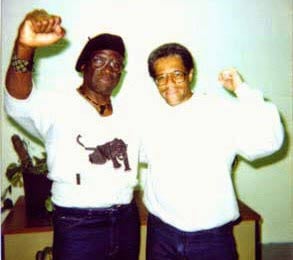

(Photo: Albert Woodfox, left, with Kenny ‘Zulu’ Whitmore, right, in 2009.)The remarks by Burl Cain in 2008 and 2014 are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ when it comes to misrepresenting the Black Panther Party. “Until history is accurately told, this type of misinformation will live on and we will all suffer as a result of it,” argues Southern University Law professor Angela A. Allen-Bell in the interview featured below. Her new article, published by the Journal of Law and Social Deviance, entitled “Activism Unshackled & Justice Unchained: A Call to Make a Human Right Out of One of the Most Calamitous Human Wrongs to Have Taken Place on American Soil,” turns the tables on the anti-BPP rhetoric by asking if what the BPP sustained at the hands of government officials is itself akin to domestic terrorism.

(Photo: Albert Woodfox, left, with Kenny ‘Zulu’ Whitmore, right, in 2009.)The remarks by Burl Cain in 2008 and 2014 are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ when it comes to misrepresenting the Black Panther Party. “Until history is accurately told, this type of misinformation will live on and we will all suffer as a result of it,” argues Southern University Law professor Angela A. Allen-Bell in the interview featured below. Her new article, published by the Journal of Law and Social Deviance, entitled “Activism Unshackled & Justice Unchained: A Call to Make a Human Right Out of One of the Most Calamitous Human Wrongs to Have Taken Place on American Soil,” turns the tables on the anti-BPP rhetoric by asking if what the BPP sustained at the hands of government officials is itself akin to domestic terrorism.

In “Activism Unshackled & Justice Unchained,” Prof. Bell concludes that the US government’s multi-faceted response to the BPP, primarily within the framework of the FBI’s infamous COINTELPRO, was indeed the very definition of terrorism. Bell writes that “the magnitude of the unwarranted harm done to the BPP has not yet been explored in an appropriate fashion. Much like a fugitive, it has eluded justice.” As a result, “the FBI’s full-scale assault on the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s remains an open wound for the nation itself. This is more than a national tragedy; this is a human wrong.”

Several pages of Bell’s new article examine the case of the Angola 3 in the context of the broader government repression faced by the Black Panthers. Bell is no stranger to the Angola 3 case. Her 2012 article written for the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, entitled “Perception Profiling & Prolonged Solitary Confinement Viewed Through the Lens of the Angola 3 Case: When Prison Officials Become Judges, Judges Become Visually Challenged and Justice Becomes Legally Blind,” used the Angola 3 case as a springboard for examining the broader use of solitary confinement in US prisons.

We interviewed Bell previously, following the release of her 2012 law journal article. Since the Angola 3 News project began in 2009, we have conducted interviews focusing on many different aspects of the Black Panther Party and the organization’s legacy today, including: Remembering Safiya Bukhari, COINTELPRO and the Omaha Two, The Black Panther Party and Revolutionary Art, Dylcia and Cisco on Panthers and Independistas, “We Called Ourselves the Children of Malcolm,” Medical Self Defense and the Black Panther Party, and The Black Panther Party’s Living Legacy.

It’s About Time BPP at the first BPP office in Oakland, CA.)” width=”640″ height=”360″ />(Photo: Billy X Jennings of It’s About Time BPP at the first BPP office in Oakland, CA.)

It’s About Time BPP at the first BPP office in Oakland, CA.)” width=”640″ height=”360″ />(Photo: Billy X Jennings of It’s About Time BPP at the first BPP office in Oakland, CA.)

Angola 3 News: Let’s begin by examining the word ‘terrorist.’ How is this defined?

Angela A. Allen-Bell: For my article, I accept the view that a terrorist commits atrocities in an attempt to influence the behavior of the general population and the government. Their intended victims are not those they kill or harm, but rather are the government and the millions of people they hope to terrorize into some desired change of behavior.

The US government’s definition of terrorism is not uniform and varies among different branches of the police, military, and US government. Some suggest that even the best intentions would result in an unclear definition, given the fact that any number of acts could constitute an act of terrorism, including offenses not yet conceived. Others suggest the lack of a specific definition is deliberate. In their book, Unchecked and Unbalanced: Presidential Power in a Time of Terror, authors Frederick A. O. Schwarz Jr. and Aziz Z. Huq suggest terrorism to be nothing more than a “political communications strategy” and a “preexisting neoconservative blueprint for a more interventionist American foreign policy, especially in the Middle East.”

Regardless of the reason for the current difficulty in adopting a uniform understanding of what is meant by ‘terrorism’ and ‘terrorist,’ the lack of a reliable definition comes at a price. In his article entitled, “A Human Rights Approach to Counter-Terrorism,” Mark D. Kielsgard writes: “On a larger scale, the lack of a definition diminishes the word’s use to a watered-down expression that can mean virtually anything. Allegorically speaking, the terrorist is the new nameless enemy, which to some may include all foreigners, immigrants, welfare recipients, or democrats, to name only a few. Terrorist has become the twenty-first century equivalent of communist, a generic term of derision whether the target perpetrates violence or just maintains a different point of view. It has entered the lexicon as a propaganda tool to label competing ideologies and promote fear and bigotry.”

With this understanding, consumers of information must listen with a discerning ear when these amorphous labels are assigned to the BPP or to other individuals and groups.

A3N: In your new article you directly confront the mainstream portrayal of the BPP as being a ‘terrorist’ group. Since you conclude that they were not in fact ‘terrorists,’ can you please explain how and why you reached this conclusion?

AB: From the outset, I wish to note that my responses apply to the Black Panther Party (BPP), not the New Black Panther Party.

There are several competing reasons in support of my conclusion that the BPP was not a terrorist organization, the first of which involves two official reports issued by bodies acting on behalf of the government. Both reports were based on thorough investigations that included extensive witness testimony.

The Church Committee Report of 1976 established that they were victims of government excesses and the 1971 Report by the Committee on International Security, House of Representatives, entitled “Gun-Barrel Politics,” while having almost nothing positive to say about the BPP, did not find that they had an agenda to kill or harm solely for the purpose of making a political statement and also did not find that they had the means to accomplish this even if such an agenda existed. Therefore, my first reason for reaching the conclusion that the BPP was not a terrorist organization is the absence of any credible, official findings establishing that they were.

My second reason involves the extensive surveillance used by the government against the BPP. I have reviewed volumes of these declassified documents and have found nothing to support a conclusion that the organization was out to kill or harm in order to make a political point.

My last reason involves my extensive research on the topic. I have read countless court cases, books, documents, interviews and articles. I have even discussed the topic with BPP members and key figures. In all of this, no credible plot to kill or harm in order to make a political point has ever emerged.

A3N: If, as you argue, the BPP was not in fact a ‘terrorist group,’ what do you think it was about the BPP that the government actually did feel threatened by? Why did they choose to undertake the well-documented campaign of repression undertaken by the FBI as part of COINTELPRO?

AB: I once read a book written by a man who inspires others to live life without boundaries or limitations. In this book entitled, Solitary Refinement, Christopher Coleman makes a profound inquiry. He asks: when was the most dangerous time in the life of a slave?

One might think the correct response to be when the slave was caught attempting an escape or when he talked back or disobeyed. However, Mr. Coleman forces us to see past the superficial and argues that the most dangerous time is when the slave actually accepts the fact that he is a slave because, at that very moment, bondage becomes self-inflicted and the slave becomes his own slave master. The slave no longer hopes to or attempts to change his condition. The slave simply decides to be a slave and wishes for nothing greater.

A liberated mind was really slavery’s greatest enemy and it was ultimately the BPP’s mindset that made the government so uneasy. In my article, I explained: “The BPP did not believe in pleading, begging, praying or patiently waiting for equal rights to be conferred. They felt equality was a birthright, demanding it was a duty, having it delayed was an insult and compromise was tantamount to social and political suicide.” They refused to accept inequality and injustice. If they had succeeded in awakening the inner slave in marginalized Americans, there would have been important political change in the US. COINTELPRO was undertaken to prevent these positive changes, to therefore “neutralize” the BPP and to quell their ability to awaken the populace from a self-inflicted state of bondage.

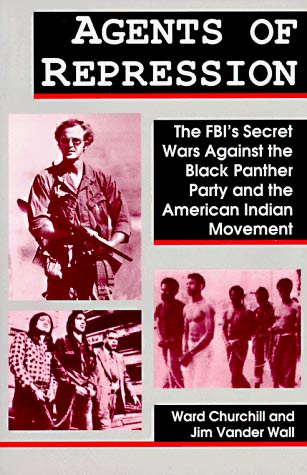

(Photo: Important book on COINTELPRO)A3N: This leads us to the next core argument of your article: that the US government’s response to the growth of the BPP, largely associated with COINTELPRO, was itself ‘terrorist.’ Can you please explain how and why you reached this conclusion?

(Photo: Important book on COINTELPRO)A3N: This leads us to the next core argument of your article: that the US government’s response to the growth of the BPP, largely associated with COINTELPRO, was itself ‘terrorist.’ Can you please explain how and why you reached this conclusion?

AB: I reach the following conclusion in my article: “If a domestic terrorist engages in acts that are dangerous to human life and does so on American soil for the purpose of intimidating people or coercing people through mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping, then there is an argument to be made that the BPP is a victim of something akin to domestic terrorism—and perhaps more—and there has been no official accountability.”

As mentioned in the article, The Patriot Act defines domestic terrorism. The first part of the definition requires the existence of an activity occurring primarily within the US. As for establishing an ‘activity,’ the FBI had declared ‘war’ on the BPP. In an effort to establish that the activity occurred primarily within the US, the article mentions that all COINTELPRO activity was first approved by high ranking, executive level officials who were acting under the badge of official authority and as arms of the US government.

The second part of the definition involves acts dangerous to human life. The article documents how every aspect of the government’s covert operations against the BPP was dangerous to human life, including both the lives of the Panthers and the many innocent people who suffered collateral damage. The baseless raids where officers were over armed (such as the raid on the New Orleans Panthers), the pretextual stops used to justify illegal arrests or to incite violence, and the periods of unjust incarceration were all extremely dangerous to human life.

The third part of the definition involves a violation of the criminal laws of the United States. The article chronicles a number of official actions that were in violation of criminal laws, such as assassinating individuals who are in no way posing a physical threat, engaging in torture, and manufacturing criminal cases.

The final part of the definition requires that the act appears to be intended to intimidate or coerce civilians, influence government policy by intimidation or coercion, or affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping. Then FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover demanded that the FBI “destroy what the [BPP] [stood] for and “eradicate its serve the people programs.” My article details the numerous ways this dictate was implemented then found that there “are but a few explanations for the stated techniques and that is to intimidate people into conforming to a single belief system, to influence government policy, by intimidation or coercion, so as to eliminate alternative approaches or to affect the conduct of government by mass destruction, assassination or kidnapping.”

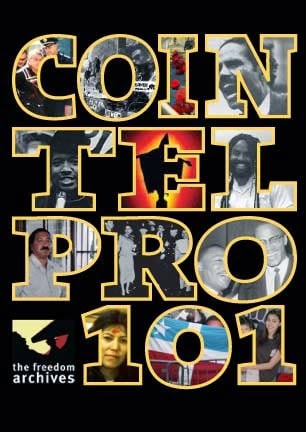

(Photo: Important film about COINTELPRO)A3N: Along with the story of the NOLA Panthers, you also examine the case of the Angola 3 and the Angola Prison BPP chapter started by Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox (Robert King joined the BPP chapter upon arrival at Angola in 1972). Given that the Angola BPP organized non-violent work and hunger strikes, as well as multiethnic and collective self-defense against the widespread rape epidemic, how do these activities contrast with or resemble ‘terrorism?’

(Photo: Important film about COINTELPRO)A3N: Along with the story of the NOLA Panthers, you also examine the case of the Angola 3 and the Angola Prison BPP chapter started by Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox (Robert King joined the BPP chapter upon arrival at Angola in 1972). Given that the Angola BPP organized non-violent work and hunger strikes, as well as multiethnic and collective self-defense against the widespread rape epidemic, how do these activities contrast with or resemble ‘terrorism?’

AB: As noted, one aspect of the definition of domestic terrorism is the violation of the criminal laws of the US. The Angola 3 case was used in the article as an illustration of a possible violation of the criminal laws of the US committed by official actors in their terrorism against the BPP.

The Angola 3’s BPP organizing was behind the walls of Louisiana State Penitentiary (commonly referred to as, “Angola.”). Beginning in the 1960s, at this former slave plantation, select inmates were provided arms and used as guards to oversee inmates working the fields. These inmates were given authority to shoot anyone who stepped outside of an imaginary boundary. In addition to this, Angola was segregated in the early 1970s and was the subject of regular litigation. Multiple courts found that state and federal constitutional violations were rampant and violence was comparable to that found in a warring territory.

Instead of engaging in predatory behavior, the Angola 3 courageously chose to teach their newly discovered Panther awareness to fellow inmates. They did this in an attempt to change the culture from one of violence, corruption and predatory behavior to one of mutual respect. They hoped to create a sense of community amongst the men and they hoped to hold the administration to a standard.

They wanted an institution that was safe and one that afforded inmates all the rights promised to them under state, federal and international law. They actively organized against inmate-on-inmate violence and rape. They successfully litigated many favorable changes for prisoners. I have observed many parents thank them for various transforming acts of service done on behalf of other inmates. Their intentions were noble, their efforts were heroic and their accomplishments were far-reaching. In essence, they did for no pay what state officials were paid to do: better conditions behind bars.

(Herman Wallace, left, with Albert Woodfox, right)The only thing that resembles terrorism in this case is the conduct of some of the government’s official actors, such as the prosecutors who have engaged in years of documented misconduct and those who have engaged in and defended the use of torture.

(Herman Wallace, left, with Albert Woodfox, right)The only thing that resembles terrorism in this case is the conduct of some of the government’s official actors, such as the prosecutors who have engaged in years of documented misconduct and those who have engaged in and defended the use of torture.

A3N: The Angola 3 and supporters have always argued that the convictions of Herman and Albert for the murder of prison guard Brent Miller, were a frame-up orchestrated in retaliation for Herman and Albert’s political activities as BPP organizers. Do you consider this to be a credible argument? Do you consider their convictions and placement in solitary confinement to be politically motivated?

AB: Yes to both. One should not overlook the timing of the government’s plot to neutralize the BPP and the timing of the (post-incarceration) convictions of Robert King, Albert Woodfox and the late Herman Wallace. They were openly acting as BPP members at a time when the government was on a mission to neutralize the BPP.

Years removed, we have learned of many BPP members who were framed for crimes they did not commit and who were subsequently submitted to prolonged solitary confinement while in prison. Some of these are referenced in the article. False convictions were used as a means of neutralization and solitary confinement was used to break their wills and end their activism. This is no longer speculation. This is now a documented fact.

When one looks at the lack of credible evidence in the Angola 3 case and couples it with the public statements of official actors, which cement (not suggest) the belief that the Angola 3 have been treated as inhumanely as they have because of their BPP involvement, one can’t help but entertain the thought that there is more at work than the murder of an innocent guard who was met with a fate he absolutely did not deserve.

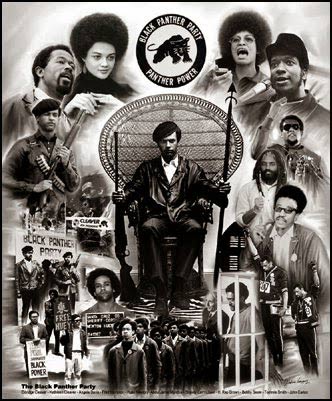

(Photo: BPP collage by Its About Time BPP.)A3N: On a personal level, after researching the BPP and writing your article, what do you find most inspiring about the BPP legacy? What lessons do you think today’s activists can learn from studying BPP history?

(Photo: BPP collage by Its About Time BPP.)A3N: On a personal level, after researching the BPP and writing your article, what do you find most inspiring about the BPP legacy? What lessons do you think today’s activists can learn from studying BPP history?

AB: The late Derrick Bell is one of my favorite authors. He teaches that courage can’t be gauged until the act that we think is courageous is viewed in context. Putting the actions of the BPP in its proper social context makes a case for how courageous they were.

They watched Martin Luther King attempt change through nonviolent means. They had seen the emergence of the Deacons for Defense. They had witnessed the Freedom Riders, who were young and innocent children harmed as well as many other protesters who were savagely beaten, killed and/or jailed for doing nothing more than attempting to make America a just place (and doing so in a nonviolent way and without being armed). They knew that law enforcement often acted to uphold segregationist laws and policies. Police regularly treated activists, protestors and those practicing civil disobedience as common criminals and many dished out violence in generous portions at civil rights events. Not intimidated by this, the Panthers still took center stage. They teach us penetrating lessons in courage.

Most of the Panthers were very young. They had nothing more than a thirst for change, a will to work hard in service to others and a commitment to studying other change agents in an effort to craft a strategy for change in this country. They illuminate the point that, to make meaningful and eternal change, one does not have to be a certain age and one does not have to have titles or credentials. They also teach us that world changers can’t be impulsive, reactionary or emotional people. Instead, they must be visionaries and wise strategists who are measured in their reactions and deliberate in their actions. The Panthers were proponents of (legitimate) education and everything they did was done after much study and deliberation. This should not be overlooked.

Most inspiring is their selflessness and genuineness. They served the people out of love. They did not seek payment or votes. They did not come with an agenda. They teach us a lot about our current leaders who will often do nothing without the promise of pay, glory or promotion.

A3N: Based upon your research and examination of the topic, why do you think Cain and others like him continue to misrepresent what the BPP was about?

AB: There is an explanation for why the misrepresentation of the BPP has continued all these years, but it is complex.

The initial reason for the perception of the BPP being violent and racist is the government itself. The declassified documents verify that a part of its neutralization strategy was to discredit them in the public’s eye. This was done in an attempt to stop people from joining, following or supporting the party. The article lists the myriad of ways this plan was brought to fruition. One way was to use infiltrators and informants to join the party then have these individuals behave badly and violently so it would appear that the BPP was nothing more than a group of thugs and outlaws. Another way the government contributed to the negative perception of the Panthers is in the way they often responded with exaggerated force where the Panthers were concerned and often initiated violent encounters and when violence erupted, sole fault was assigned to the Panthers. Mainstream history will have you believe they always directed violence towards the police who were always innocent and honorable in their interactions with the Panthers. Evidence simply does not bear this out.

A second reason for the negative image was the media. The declassified documents also establish that certain members of the media worked with the government to publicize only negative images and adverse press about the BPP. It is a known fact that repetition is one of the most effective advertising tools. And so certain media outlets went to work in reporting as much bad as it could and made certain not to air anything positive about the BPP. The impact of this is generations of people who have no idea that the BPP was a service organization that laid the groundwork for many social programs that we currently enjoy, such as community policing, health care for the poor, sickle-cell anemia treatment and testing, free meals in school and food distribution to poor families. Their acts of service to the community was quite extensive—they served as watchdogs over the police, escorts to the elderly, community organizers and a host of other things that are discussed in detail in my article.

The third reason for the misrepresentation is the sanitized history that we are taught in schools. History has never been presented honestly where the Panthers are concerned. As a result, many people perceive them as an anti-government, violent, gun-toting militia group. The practical impact of this is that anything associated with the BPP is still vilified. We saw this recently in the instances of BPP member Joanne Deborah Chesimard (also known as Assata Shakur) being placed on the terrorist watch list and Debo Patrick Adegbile, a respected lawyer who was never a Black Panther, but he recently suffered the same ostracizing that they have. As head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, he acted on behalf of Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former Panther whose death sentence was recently overturned after spending nearly 30 years in solitary confinement on death row. Senators blocked President Obama’s nomination of Mr. Adegbile to lead the Justice Department’s civil rights division because of this.

Until history is accurately told, this type of misinformation will live on and we will all suffer as a result of it. This is exactly why I wrote the article and it is why I am working so passionately on this topic.

(Photo: Herman Wallace’s memorial service on Oct. 12, 2013. Image by Ann Harkness)

(Photo: Herman Wallace’s memorial service on Oct. 12, 2013. Image by Ann Harkness)

A3N: Any closing thoughts?

AB: Yes, a few brief points.

At the memorial service for the late Herman Wallace, BPP member Malik Rahim commented that we would not see black-on-black crime as we do today if the Panthers were allowed to do the work they started in the community. I would add the same to be true when it comes to many other social ills. Along these same lines, it is quite intriguing that the Panthers started in response to police violence. They often followed police to ensure the public was safe in their interactions with the police. Years removed, we still find ourselves in need of such intermediaries. If their work had not been cut short, would we find ourselves better off?

(Poster by artist César Maxit)Redress is broader than justice. I strongly believe redress is in order and I believe we have reached the appointed time. I do not advocate for a monetary payout. I advocate for amnesty, release of BPP members who remain in custody as a result of their BPP involvement, and for the correction and memorializing of history where the BPP is concerned.

(Poster by artist César Maxit)Redress is broader than justice. I strongly believe redress is in order and I believe we have reached the appointed time. I do not advocate for a monetary payout. I advocate for amnesty, release of BPP members who remain in custody as a result of their BPP involvement, and for the correction and memorializing of history where the BPP is concerned.

I would be honored if folks would read the article in its entirety. I end with this excerpt from the conclusion of my article:

“Of course, this article is written with all the benefits that accompany hindsight. It is only fair to recognize that the government, at the time of the BPPs activism, was littered with competing forces, interests and pressures and the advent of new demands being placed upon it. Not only were these things taxing, but the situation intensified because there were no breaks in tensions. They came simultaneously and in close proximity so as not to allow time for rational thought to take command and there was no precedent to serve as a blueprint. Add to this gumbo mixture, a government being confronted with the likes of the BPP for the first time in history. When one comes to terms with the complexities of the situation and can appreciate how they were magnified by the setting within which these developments unfolded, one is forced to bear a degree of understanding for how such a tragedy was set in motion. While these things must be taken into account if the discussion is to remain honest and impartial, they must not serve as exit points or escape routes for those seeking a way out of this conversation vis-a-via the path of least resistance.”

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $34,000 in the next 5 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.