Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

Do you really need to own Boardwalk and Park Place and all the associated property to be a winner? That’s how it works with Monopoly. But isn’t that the sort of board game teaching the wrong lessons to our children – and to us?

Don’t we have enough corporations and businesses monopolizing our economy and owning our government?

Enter Co-opoly, a board game where cooperative business are developed through team strategy. In short, sharing knowledge and creating cooperative strategies determine whether everyone wins or everyone loses. It’s not about an individual grabbing up all the wealth and bankrupting others; it’s about the economic success of people working together.

Co-opoly is the creation of The Toolbox for Education and Social Action (TESA), a worker-owned cooperative based out of Northampton, Massachusetts. They create and distribute educational resources on social and economic change for activists, organizers and educators. TESA also partners with other social justice organizations to build the materials and programs they need to effectively teach about their causes.

The Toolbox for Education and Social Action created Co-opoly. (Photo: TESA)

The Toolbox for Education and Social Action created Co-opoly. (Photo: TESA)

Brian Van Slyke is a worker-owner at TESA. He has created educational resources on subjects ranging from people’s history to social change movements and the cooperative movement.

Truthout recently interviewed Van Slyke about Co-opoly, its creation and its challenge to Monopoly.

Mark Karlin: Clearly Co-opoly is a creative alternative (boosting the cooperative movement) to Monopoly, the ultimate game of capitalism. Can you explain your organization and how you came up with the idea for Co-opoly?

Brian Van Slyke: One of the interesting things about Monopoly is that people often promote it as a good way to teach about financial literacy, even though the way you win is by obliterating all of your opponents and leaving them in economic ruin. What many people don’t know about Monopoly is that it was actually created to teach about the dangers of cutthroat capitalism. The original version was called The Landlord’s Game, and it was used in the Great Depression as an underground game and organizing tool to teach tenants about how they were being ripped off. Its creator, Elizabeth Magie, had her vision corrupted – and now we know Monopoly as the game that’s a shining example of American capitalism.

So, what Monopoly does so perfectly is present the problem. We created Co-opoly to offer the solution.

Originally, we came up with Co-opoly: The Game of Cooperatives based out of a need we saw through our work in the cooperative movement. We wanted to give people a way to not only learn about co-ops and the immense benefits they have for individuals and their communities, but also to allow people to experience cooperation. Co-opoly actually started with the intention of being a 15-minute role-play activity for a workshop, but it kept building and expanding until one day we had a board game prototype! We spent three years traveling around the country, testing it out with game designers, co-op enthusiasts, educators and people at conferences. During this time, we took in all of their input and advice. In the end, we came up with something that is an incredibly fun game and is also a great tool for building the cooperative movement and a democratic economy.

Mark Karlin: On the box cover of the game, it says, “Where everyone wins or everyone loses.” So we can safely assume a billionaire hedge fund operator would not like Co-opoly. Is that a safe assumption?

Brian Van Slyke: I’d go out on a limb and say that’s a safe assumption.

In fact, you could even say these hedge fund billionaires are the villains of Co-opoly. The main nemesis in Co-opoly that players struggle against together is the Point Bank. The Point Bank essentially symbolizes the economy of exploitation, big bankers, as well as the system of profit over people and the planet.

I’d also say that Co-opoly’s philosophy is antithetical to the values of these hedge fund billionaires and big bankers because everyone’s in it together. In Co-opoly, people are playing as individual members of the co-op as well as the whole co-op itself. People can lose Co-opoly in two ways. First, if a single player goes bankrupt, then everyone loses. Second, if the co-op as a whole goes under, everyone loses. Perhaps particularly infuriating to lovers of cutthroat capitalism is that players win Co-opoly together by starting another co-op in their community. Essentially, the way people win Co-opoly is by springboarding the cooperative movement in their community.

Luckily, we don’t feel so bad alienating these billionaires – the world happens to comprise primarily non-billionaires. In fact, we’re currently on our second pressing of Co-opoly, as we sold out of the first pressing in under a year, so it is safe to say that many people feel the same way about the billionaires. The game has been distributed in roughly 30 countries – from the US to the UK, Spain, Malaysia, Chile, Australia, India, Hungary, Greece and many more.

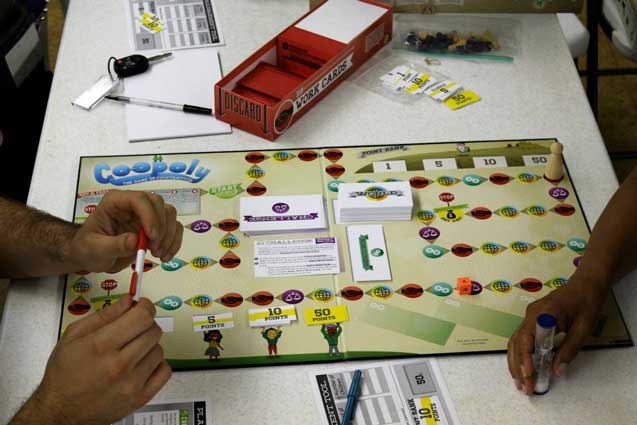

Only working together as a team can you win Co-opoly. (Photo: Fund for Democratic Communities)

Only working together as a team can you win Co-opoly. (Photo: Fund for Democratic Communities)

Mark Karlin: Can you briefly describe how the game is played?

Brian Van Slyke: At the start of each game, players come up with a co-op that they are going to play as. As they play, the game teases out their co-op’s story. As players go around the board, they run into different opportunities, hurdles and life events they have to overcome together.

There’s a lot of laughter and heart-pounding fun in Co-opoly. When players land on the “Work” spaces, they play mini-games of charades, drawing, or unspoken – this is how they earn points (the game’s currency) for their co-op.

People often say to us when they first hear about Co-opoly: Yes, it sounds great, but is it actually any fun? Honestly, we think it is. (Of course, we might be a little biased.) Co-opoly was designed so that its lessons don’t hit you over the head.

You learn while while you’re laughing and talking and strategizing, and a lot of these lessons hit home upon reflection. Co-opoly was built so that it could be used as a versatile tool, a good time, or both. You can also watch a video about how the game is played.

Mark Karlin: It’s ingrained in the national myth of American individualism that economic opportunity is an individual endeavor. How does Co-opoly educate players about working together to create an economic alternative to “everyone is in this for themselves”?

Brian Van Slyke: In Co-opoly, players come to understand that their interests and needs will not always align – but that they have to work together to survive. For instance, you might want to buy the child care card, but I, as a player without a child, don’t get any direct benefit from it. Yet, if you go bankrupt because we didn’t support you, we all lose. So, as a group we have to figure out if it’s worth purchasing or not.

That is the beauty of the game; it turns the “I’ll only care about myself” mentality on its head. Even if buying the child care card benefits you and not directly me, I’m still in trouble if you’re in danger of going bankrupt. The thing that makes Co-opoly exemplary is that players consistently see that their fate and well-being is directly tied to the success of their whole group (the co-op) as well as the other players.

Mark Karlin: Truthout continually focuses on the growing cooperative movement, but many Americans are unaware of cooperatives as an option for an employment model. Can you discuss the state of cooperatives in the United States?

Brian Van Slyke: The cooperative movement has a long history in the United States. Most recently, though, it’s become a growing trend as a response to the global economic meltdown. As CEOs continue to make big bucks off of exploited labor and governments continue to slash social safety nets, people are realizing they’re going to have to come together if they want to make it.

Many workers are turning toward the co-op model to create their own fair jobs. Some are taking over failing businesses and turning them around, such as the Just Crust pizzeria in Boston. This also includes the inspiring story of the workers who occupied the Republic Windows and Doors factory in Chicago and are now turning it into the New Era Windows Cooperative. In addition, some groups are working with historically exploited peoples to found their own co-ops. WAGES (Women’s Action to Gain Economic Security), for example, is working with primarily Latina women in California to develop eco-friendly home cleaning services. There are also co-op networks springing up around the country meant to help co-ops supply mutual aid to one another, like the Valley Alliance of Worker Co-ops and the US Federation of Worker Co-ops. Both of these are organizations in which TESA has membership.

Of course, the co-op movement faces many hurdles, including the fact that most people don’t have experience with practicing everyday economic democracy (and this is also where I’d argue Co-opoly comes in), and it can be difficult to access startup capital. Still, the co-op movement in the United States is growing. This is because this so-called recovery has made us collectively realize something: when people say we need jobs, that’s simply not enough. What we need are good jobs that are democratically owned and controlled by the people in the communities.

Mark Karlin: One of the major mantras in the US is that the individual enterprise is necessary for democracy, but aren’t cooperatives the ultimate financial model of a democratic workplace?

Brian Van Slyke: The funny thing about a lot of people who promote American democracy is that they seem to think democracy should only be practiced by voting once every few years. Even then you’re only voting for someone else to, maybe, represent your views. The beauty about the cooperative movement is that it makes democracy a daily reality. Our system of government might have some semblance of democracy, but the rest of our society, and especially our economy, is based on hierarchy, exploitation and profit. In turn, I would ask: how can we have a truly democratic society without having lots of small, little, everyday democracies? In reality, it’s just not possible.

Co-ops are businesses owned and operated democratically by a specific set of people. Each member, or owner, only has one share and one vote in the co-op. When there are good times, these co-op members share the benefits equally; and during the hard times, they share the burdens equitably. There are co-op coffee shops, grocery stores, print shops, bike delivery services, house cleaners, factories, artist stores, farms, grocery stores and so much more. These co-ops are run by the membership together, and people have to make decisions regarding big and small challenges and opportunities together.

In some ways, I think that’s what scares people who are used to hoarding wealth: the idea of democracy in the workplace and the economy would mean their reign would come to an end. Of course, that’s the same thing that excites so many others – that we could really be in charge of our lives and communities.

Mark Karlin: There are several different types of cooperatives. Can you name and describe a few of them?

Brian Van Slyke: There are certainly different types of cooperative models, including housing co-ops, worker co-ops, consumer co-ops, producer co-ops, artist co-ops and more.

What makes an organization a co-op is its one-member, one-vote structure. Defining the membership defines the type of co-op. For example, if the workers at a home improvement store own the business together equally, it’s a worker co-op. An example of another kind of co-op is one that is consumer owned, such as a food co-op, where customers can buy one share of the co-op and make decisions on issues such as board structures, product prices and what the store stocks.

Worker and consumer co-ops can be huge or very small. For example, my co-op, TESA, is only four people. Equal Exchange, a worker co-op distributor of fair trade goods, has roughly 100 worker-owners. Union Cab, a worker co-op taxi service in Madison Wisconsin, has more than 200 worker-owners. The Mondragon co-op system in the Basque region of Spain has nearly 200 worker co-ops and almost 100,000 worker-owners.

Mark Karlin: Part of Co-opoly’s educational goal is to show that people learn to work together. Yet, those individuals forming cooperatives may experience a failure at first. How is that reflected in the board game?

Brian Van Slyke: Losing the game is a very real possibility. In fact, I’d say people only win about half the time.

We live in a cutthroat economic world that isn’t friendly to most people, and starting a business – co-op or not – is a real struggle. In Co-opoly, players come up against personal as well as group challenges that threaten their ability to win. Players can have mounting medical bills. The group could decide to take on a risk they think will pay off but goes wrong instead. The Point Bank could prey on the co-op. The economy could collapse. The cost of housing could skyrocket. But always, everyone is in it together.

Of course, the point of co-ops is to help share this burden equitably amongst members, and this allows co-ops to survive in many situations where normal businesses would shut down. A brief illustration of this point: a 2008 study by Quebec’s government demonstrated that around 62 percent of new co-ops in the province were still open after five years. The traditional models of business in the region, on the other hand, had a five-year survival rate of only 35 percent. That is a staggering difference!

Mark Karlin: Can you describe a bit more The Toolbox for Education and Social Action? Is it a cooperative?

Brian Van Slyke: Yes, TESA is a worker-owned cooperative, and we were founded in the summer of 2010. We build educational resources for social, economic and environmental change movements. Some of these are products we create in-house, like Co-opoly. In addition, we also partner with organizations to build resources for their campaigns and causes.

We believe that democratic and popular education is vital for building more just communities and a more democratic, equitable world. Many social and economic change movements either don’t use education to its fullest extent, or employ hierarchical forms of education that don’t empower learners to include their own needs and take action. Our mission is to provide the materials and opportunities for organizations, individuals and movements to be able to actually use participatory forms of education that develop people’s abilities to make a difference in their lives and communities.

We’ve worked with organizations such as the Green Worker Cooperatives, the War Resisters League, the New England Farm Workers Council, In Solidarity with (Im)migrants, Youth Action Coalition, the Center for Workplace Democracy, the Cooperative Development Institute and more. Through these partnerships, we’ve helped the organizations build one-day conferences, workshops, lesson plans, their own games, curricula, handbooks and self-education materials for their membership. We’re open to hearing from any group working towards social, economic and environmental justice about working together!

Mark Karlin: How can someone who wants to learn how a cooperative team works obtain the board game?

Brian Van Slyke: I’m glad you asked! The best place to get Co-opoly: The Game of Cooperatives is from our online store. We also offer an extensive set of other co-op resources on our site – posters, reading materials, workshops and education kits.

Co-opoly and our other co-op materials have been used in community organizing spaces, by people trying to turn their businesses into co-ops, by people looking to start co-ops, by families looking to have a game night where everyone doesn’t hate each other at the end, between friends, by existing co-ops looking to do membership outreach or internal education, and much more.

Going forward, we are going to be creating more resources, such as curricula and other games on social justice issues. We release free materials and curricula on a weekly basis, and in the middle of this month, we will start to sell resource bundles full of educational materials, DIY projects, primers and more. Our first focus is on how labor is striking back against the ongoing corporate onslaught against workers and everyday people.

People who want to stay up to date with the materials we’re releasing should follow us on Twitter and Facebook, or sign up for our mailing list.

You can purchase Co-opoly on TESA’s web site and enjoy playing it with friends and family.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.