Part 1 – Project corn

Ambroise Pierre is one of the Haiti's better-off small farmers. His tiny plots and larger tracts near Croix des Bouquets add up to one carreau – 1.29 hectares or 3.18 acres – of land.

Still, the 73-year-old struggles to make ends meet, to feed family and to send the children to school. So, when he was offered what he calls

“project corn” seed at a low price last spring, he bought some and sowed it in one of his fields.

“It made really tall plants! It looks good from afar, but up close you could see that it was useless,” Pierre said. “It had no ears.”

Pierre gestured to a now-empty field where he had planted the “project corn” he got from a $126 million dollar, US government-funded program called WINNER (Watershed Initiative for National Natural Environmental Resources). According to its website, one of WINNER's goals is to help famers “increase their productivity and to double their incomes in five years” through the use of better irrigation and techniques, and by using better seeds, fertilizers, and other inputs provided at only a tenth the of actual cost through “Farmer's Stores” run by local farmers organizations.

(USAID/WINNER is one of the two projects that accepted the controversial gift from Monsanto of seeds last spring. Pierre did not plant Monsanto hybrid corn, which we deal with in Monsanto in Haiti. Haiti Grassroots Watch's numerous requests to WINNER for an interview to ask about Pierre's corn, Monsanto seeds and other issues were turned down.)

Pierre happily bought the low-cost seed – which WINNER's partner, a local farmers association, said was the “chicken corn” variety, but which was supplied in unlabeled, white bags: no name, no information on whether or not the seed was chemically treated (many corn seeds are coated with fungicide), no warnings.

“The price. That's why a lot of people rushed and planted it,” Pierre explained.

Ambroise Pierre

shows a reporter how strong and tall his corn, grown from his own seed, stand.

This season Pierre is planting the way most Haitian farmers plant: using a local corn variety he knows, with seeds from a previous harvest. The yield will be much lower than if he used an “improved” or “quality” seed variety – whether open-pollinated or hybrid – but it is something he knows, and something whose supply will never run out.

But were he offered, free or low-cost “project seeds,” would he take them? And what kind would be good for him?

When Haiti Grassroots Watch posed the question, a farmer who had been trained by WINNER whispered: “Say 'hybrid'! Say 'Monsanto!' Say 'Monsanto!'” but Pierre didn't understand. [See “Monsanto in Haiti“.]

Still, the old farmer said: “Getting a gift is a marvelous thing! If it is something that's guaranteed… but I need a guarantee. And if I have to buy it one year, but I don't have money, that could be a problem.”

Ambroise Pierre is one of hundreds of thousands of Haitian farmers who got free or subsidized seeds last year as part of the emergency response to the January 12, 2010, earthquake.

His experience – especially his crop's failure – might not be typical, but his dilemma illustrates the challenges facing farmers here:

• Should a farmer accept free or subsidized seed that he or she doesn't know, without training or assistance?

• What are the risks of using a new variety without training and/or without the proper additional inputs like fertilizer and irrigation?

• Is using gifted or subsidized seed sustainable for Haitian farmers?

And there are even broader questions, related to “humanitarian” and “development” aid:

• What kind of seeds were and are being distributed in Haiti and are they correct and safe for the environment?

• How were and are recipients being chosen? And where?

• Was the “emergency” seed distribution necessary?

• Is giving away or heavily subsidizing seed sustainable for the Haitian agricultural system and for the government?

A Need for Seed?

Soon after the January 12, 2010, earthquake, humanitarian and development organization websites and newspaper articles warned of looming famine in the countryside, saying farmers may be forced to “eat their seed.”

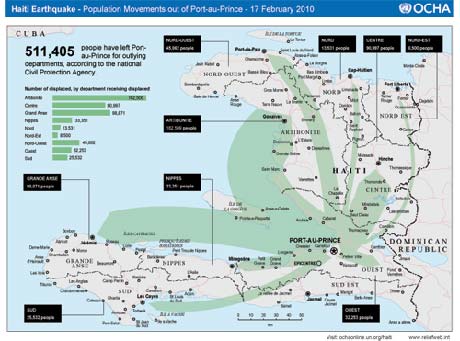

Indeed, in the days following the massive earthquake that killed some 230,000 people the capital and three smaller cities, there was an out-migration of “internally displaced people” or IDPs to rural communities. Official estimates calculated that by mid-February, over 500,000 people were staying with friends and families in small cities or rural communities. The cost of food – in the devastated capital but also throughout the country – was going up.

Map from UN Office of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA) showing where

Port-au-Prince refugees went.

The UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warned that a “food crisis looms in Haiti” and called for massive funding for the distribution of seeds and tools in the Haiti “Flash Appeal.” The “Flash Appeal” is how the UN coordinated humanitarian organizations seek funds in an emergency. The total requested was over $1.5 billion, of which 1,106,976,859 was received.

The FAO coordinated all the agriculture requests because it heads the “Agriculture Cluster.” Made up of development and humanitarian aid organizations like WINNER, Oxfam, Catholic Relief Services, ACDI-VOCA, as well as the Haitian Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Rural Development (MARDNR), the Agriculture Cluster is one of the 12 “clusters” or groups of multilateral, state and “non-governmental” actors. [See previous Haiti Grassroots Watch article on the “Cluster system“.]

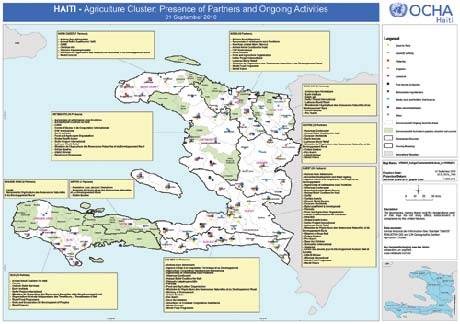

Agriculture Cluster members, as of September 1, 2010. Souce: OCHA

In the Haiti “Flash Appeal,” released on February 18, 2010, the Agriculture Cluster requested $70,640,554 for 26 projects, noting that the overall objective was “to ensure that food security is safeguarded over the next 12 months on an increasingly sustainable basis.” One of its five interventions was the distribution of seeds and planting material “to those areas and households where it is known to be in short supply.”

“The FAO thinks seeds are important. For good agriculture and for better production, you need good seeds,” the FAO's Francesco Del Re, who is also Cluster Coordinator, told Haiti Grassroots Watch. “What the FAO is doing is in accordance with the [government's] Service National Semencier (National Seed Service or SNS) and the Ministry.”

Indeed, in a March 2010 document, the MARDNR advised that $10 million be spent buying seeds “to cover at least 30 percent of the theoretical seed needs for the next three agricultural seasons.”

But as early as March 10, Catholic Relief Service – which has extensive experience in Haitian agriculture development work – released a “rapid seed assessment” report [PDF] for southern Haiti, one of the areas worst-hit by the earthquake, saying seed distribution should not take place.

Direct seed distribution should not take place given that seed is available in the local market and farmers' negative perceptions of external seed. This emergency is not the appropriate time to try to introduce improved varieties on anything more than a small scale for farmer evaluation.

But January 12, 2010, didn't create Haiti's “emergency” nor its agricultural crisis.

With virtually no state support for farmers, a skewed distribution of land, peasant's working tiny plots, and a chaotic land tenure system characterized by exploitation and outright theft, with poorly maintained irrigation systems, poor infrastructure, and with massive deforestation and hillside farming, the lack of access to improved seeds is just one aspect of a system that has been in crisis for decades. that results in stagnating or declining agricultural production. It might seem like a small factor, but improved seeds – open-pollinated or hybrid – can increase yields by 100 percent and more. In Haiti, there is no seed certification system or seed research, and most famers don't make any distinction between grains for eating and grains for sowing, and therefore don't necessarily select the best genetic stock.

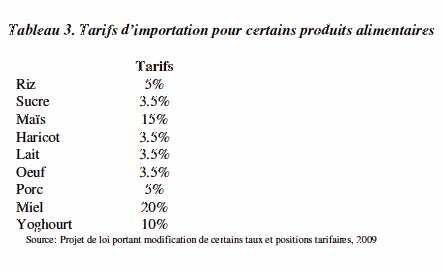

On top of the seed and other issues, however, for 15 years, Haitian agriculture has been reeling from a coup de grace: trade liberalization.

Under pressure from Washington (the Bill Clinton administration), and as part of a deal that enabled President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to return to Haiti after the 1991-1994, US-supported coup d'état, the Haitian government slashed the tariffs which had protected farmers from foreign competition.

Tarrifs on foreign agriculture goods. Source: Ministry of Agriculture.

“Almost overnight, Haiti became one of the world's most open markets,” Oxfam's Marc Cohen wrote in a recent paper.

Between 1990 and 1999, Haitian rice production fell by nearly half… From virtual self-sufficiency in 1980, today Haiti imports 80 per cent of its rice and 60 per cent of the overall food supply comes from abroad.

Part 2 – Seed emergency or chronic crisis?

The Agriculture Cluster did not get the full $70,640,554 it requested for 26 emergency projects, only $31,526,150.

“Donors have been very generous, and we are thanking them for all they did,” the FAO's Francesco Del Re, coordinator of the Cluster, told Haiti Grassroots Watch in a recent email, but “their response was far from covering the needs” of the Cluster and the Haitian Ministry of Agriculture (MARDNR).

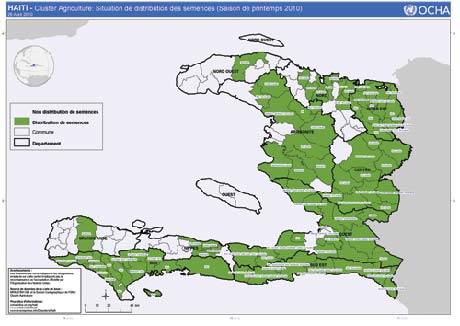

About $20 million went for the distribution of seeds, plant cuttings and tools, according to Del Re. While the exact numbers vary, according to the FAO, for the spring season alone, 2,534 MT (metric tons) of legumes and cereal seeds were handed out by Cluster members.

Agriculture Cluster map showing seed distribution for spring, 2010.

“The logic behind [the distribution] is that in the zones directly affected by the earthquake and in the zones that received a great number of displaced people, the peasants were decapitalized,” Del Re told Haiti Grassroots Watch. “It wasn't a general distribution. It was a well-targeted distribution, for the most vulnerable.”

In addition to the directly affected areas, the Cluster wanted to support the farming season in general, “to maximize food availability at a difficult moment,” Del Re told Haiti Grassroots Watch in a follow-up email.

In all, 395,000 families – perhaps one-third to one-half of Haiti's farming population – were reached during 2010.

While the MARDNR didn't coordinate the distributions, it did define a list of acceptable seeds. Importing new varieties of seeds and plants, without proper controls and tests, can lead to failures in the field and to the contamination of native strains. (It is also illegal, according to Haitian law, the World Trade Organization and international conventions to which Haiti is party.)

(Nevertheless, with the approval of Minister of Agriculture of Haiti Joanas Gué, the US-funded WINNER project distributed previously unused varieties like hybrids from PIONEER and MONSANTO. [See “Monsanto in Haiti“])

According to the MARDNR, Haitian farmers need about 11,220 MT of cereal and bean seeds each spring, meaning that according to Cluster statistics, at least 23 percent of seed needs – and probably more, since not all organizations coordinate with the Cluster – were covered for that season.

“Seed emergency” or a “chronic” problem?

But not all experts agree that Haiti faced a “seed emergency” last year.

Indeed, Del Re admitted, there are “some very strong (and fixed) opinions” and “as we are speaking, there is a very open debate over the best way to subsidize/support the Haitian agriculture.”

One of those with a strong opinion – on seeds and seed aid, at least – is Louise Sperling, Principal Researcher at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).

The researcher came to that conclusion while working on the 115-page Seed System Security Assessment/Haiti (SSSA) report [PDF], which looked at the impact of the earthquake on households and agriculture livelihoods, as well as on seed security issues.

The report, released in August but whose main findings and recommendations were distributed to Cluster members in June, was funded by US AID and carried out with the cooperation of the MARDNR, the FAO, and several large development institutions.

Sperling and her co-authors noted that the “farmers eating their seed” phenomenon was not a “seed emergency.”

“Unlike nearly everywhere else in the world, 'eating and selling one's seed' are not distress signals in Haiti: They are normal practices,” the authors noted.

So there was no “seed emergency.” Instead, farmers faced “financial constraints” (lack of cash, lack of credit) and the “deeply chronic” challenges with Haiti's seed system.

Indeed, Sperling who has worked in over 20 African countries for almost three decades, dealing with war, drought, and genocide, thought she had seen it all. Until she came to Haiti.

“I am not sure I have ever seen so little innovation,” she told Haiti Grassroots Watch in a lengthy interview via internet from Tanzania. “Small farmers have been left behind on a massive scale.”

For Sterling and the other contributors to the SSSA, the “direct seed distribution” was a poor policy choice, because it should only occur when there is a lack of seed available. In Haiti, even after the earthquake, there was adequate – albeit often genetically inferior – seed, via the informal marketplace and in some cases, via commercial providers.

[T]he type of aid response often did not match the seed security problem at hand: the immediate problem was clearly one of financial stress, which can lead to problems in accessing a range of goods, including seed. Direct seed availability was not identified as a significant constraint.

Part 3 – Seed distribution: What do farmers and the SSSA recommend? The “Seed System Security Assessment/Haiti report”, carried out in the spring and summer of 2010, concluded that Haitian farmers did not face a “seed emergency” after the earthquake, and that maybe no seeds should have been distributed.

Rather than distribute seeds, the SSSA said that cash, or a seed voucher system (which a few but not all Cluster partners used), would have been more appropriate in most cases.

Haiti Grassroots Watch findings in the field – while anecdotal because they only come from four locations – confirmed the SSSA's skepticism.

Ambroise Pierre, the Croix des Bouquets farmer with one carreau of land (much more than most farmers), didn't host IDPs, and wasn't necessarily vulnerable. While it is unclear if he got seeds via the US-funded WINNER program, or via the seed distribution (because WINNER refused numerous requests for an interview), the farmer did get subsidized seeds, but the experience was not a positive one. [See part 1]

In Bainet, on the South coast, there were few IDPs, but the US-based ACDI-VOCA organization – a member of the Agriculture Cluster – distributed bean seeds widely. However, the distribution came almost two months after the normal planting season, and many farmers in Chomèy, in the hills above Bainet, told Haiti Grassroots Watch that the plants produced no beans.

“It seems like the seeds they gave us are for plants that are used for growing on irrigated land,” farmer Joseph Maxo told Haiti Grassroots Watch.

“Next time, if another NGO wants to help us they should contact us first and we can help them find a plant that grows well here. They thought they were giving a gift but they did more harm than good,” he added.

Asked about the Bainet distribution, ACDI-VOCA Country Director Emmet Murphy said that the bean seeds were appropriate to the region. In fact, they were locally sourced.

The distribution was late specifically for that reason. Unlike many or all of the humanitarian actors, ACDI-VOCA uses local seeds, which it “lends” to farmers, who are required to give back the same amount of seeds they sowed. The earthquake threw off the seed-multiplication schedule. There were also late spring rains which negatively affected yields throughout the southeast, he said.

However, Murphy also admitted that ACDI-VOCA “doubled or tripled” its seed distribution work because of the disaster. The distributions were part of a $3,878,712 grant the organization got through the Flash Appeal.

“It's a real shame that what occurred in Bainet would be compared to a plain old distribution,” he told Haiti Grassroots Watch. “We are very careful about how we work with the FAO. We are picky about what seeds we use and where.”

Indeed, ACDI-VOCA's seed-lending process appears to be one of the more sustainable projects. It works with the MARDNR as much as possible, because “if you're not working in coordination with the government, you shouldn't be here.”

ACDI-VOCA assisted seed multiplication program.

But despite ACDI-VOCA's good intentions, the end result in Chomèy was the same.

“What I would like to tell the NGOs is that, just because we are the poorest country doesn't mean they should give us whatever, whenever,” disgruntled Chomèy farmer Jean Robert Cadichon told Haiti Grassroots Watch.

Farmers in Fondwa, in the mountains above Leogane, also reported getting seeds late.

Lionel Beauvais, a local official, told Haiti Grassroots Watch that the FAO distributed red and black bean seeds, although the ten sacks were not enough for the population. In addition, not everyone had a successful harvest. Some germinated and produced good yields, “others didn't produce anything.”

Beauvais said he and other local officials didn't request the seeds. They were just “made aware that seeds would be given.”

According to Beauvais, the seed distribution “was positive, because the tiny amount farmers received was useful, but there was also a negative side… the seeds came late and also, there weren't enough. We couldn't give everyone seeds. But everyone knew about it and was demanding them.”

A woman farmer gets seeds from an FAO worker as other farmers

watch. Source: FAO

Ernest Laguerre, who owns a store called “Ti Kay Nou Peyizan Pwodui Agrikòl” (Your Little Home Peasants’ Agricultural Products) in Kenscoff that sells supplies, fertilizer and seeds, told Haiti Grassroots Watch that the free or subsidized seed distributions and other aid programs affect his business.

“I would like to ask the NGOs to work with the seed distributors that are already here. We know the terrain, we could work for a better policy… All the NGOs, all the seed companies, we could all talk, share ideas, and then we could come up with a plan to improve agriculture.”

As in Croix des Bouquets, where Pierre's “project corn” failed, in Bainet and Fondwa, farmers were pleased with the idea of free or nearly free seeds, but they also had criticisms.

These criticisms – while anecdotal – match the findings of the SSSA which advised that seed distribution in Haiti be at least “honed,” reminding:

1. Emergency seed aid should be used only to address emergency problems, and those in which seed security is a problem. Note that current farmer projections for August/September 2010 suggest that farmers can access the seed they need.

2. Any seeds made available to farmers through aid interventions have to be shown to a) be adapted to local conditions, b) fit well with farmers preferences, and c) be of a quality 'at least as good' as what farmers normally use.

2.1 One should never introduce varieties in an emergency context which have not been tested in the given agro-ecological site and under farmers’ management conditions.

[To see the rest of the recommendations, get the report here.]

Part 4 – Seed distribution: a “mal nécessaire” (necessary evil)?

In August, 2010, a multi-agency, 115-page report recommended that seed distributions to Haitian farmers halt or be “honed” because “[e]mergency seed aid should be used only to address emergency problems, and those in which seed security is a problem.”

The “Seed System Security Assessment/Haiti (SSSA) report”, authored principally by researcher Louise Sperling of the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), found that Haiti had “deeply chronic” seed problems – mostly the lack of appropriate, quality seeds – but that Haitian farmers did not face a “seed emergency” problem per se.

Still, the seed distributions continued throughout 2010, in accordance with the original Agriculture Cluster plan and in accordance with the Ministry of Agriculture (MARDNR)'s recommendations [see Part 2], and even though by early summer, most IDPs had left the countryside.

Chart showing Port-au-Prince cell phones out of and back into the capital.

From Internal Population Displacement in Haiti, Karolinska Institutet

and Columbia University, May 14, 2010.

Some 40 percent had returned to the capital by March 11, and by June 18, 66 percent were gone, meaning that only about 125,000 IDPs remained in the countryside as of that date.

In a mid-March email exchange, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization's Francesco Del Re, coordinator of the Agriculture Cluster, explained to Haiti Grassroots Watch that not everyone agreed with all of the SSSA, and that there are “some very strong (and fixed) opinions,” adding “as we are speaking, there is a very open debate over the best way to subsidize/support the Haitian agriculture.”

At a February 8 meeting of the Agriculture Cluster, where – for the second meeting in a row, there was no apparent MADNR representative – the FAO announced that 1,508 MT of cereals and legumes and 3,082 Kg of vegetable seeds would be distributed to four departments this spring. Between 150,000 and 200,000 families will benefit from the seed, plant cutting and tool distribution, Del Re told the meeting.

“This year we won't do too much direct distribution of seeds and tools, because we want to start doing more sustainable work,” Del Re told the meeting.

When asked why only certain areas were chosen, another FAO staffer, Carmen Morales, said “these are the areas directly effected” by the earthquake, but she also added: “This is where the donors are working. Let's be clear on that.”

According to Del Re, the seed distributions are a “mal nécessaire” (a necessary evil).

“It is not optimal. It is not the kind of intervention that we prefer. It doesn't address structural problems,” he admitted, but in a later email, he added “we Cluster members are convinced that last year's intervention had a solid ground and reason to be, and that the overall impact was positive.”

And he insisted that the 2011 distribution, which is smaller than 2010, was also important.

When Sperling learned the Cluster was continuing the distributions into 2011, she made this general statement about seed distributions, via email:

Direct seed aid – when not needed , and given repetitively – does real harm. It undermines local systems, creates dependencies and stifles real commercial sector development.

Sperling didn't hesitate to identify one of motors of what she called “unneeded aid,” saying that some humanitarian actors “seem to see delivering seed aid as easy and they welcome the overhead (money) – even if their actions may hurt poor farmers.”

But Del Re also pointed out that the FAO and many other actors – like ACDI-VOCA and WINNER – are involved in agricultural development (as opposed to emergency) projects, too, such as helping develop “quality” or “improved” seeds.

In fact, the FAO has also recently requested funding for a new five million dollar program that would include financial and technical support for quality seed multiplication efforts. The request is part of the Agriculture Cluster's total of request for $43,087,517 for 22 projects for 2011.

But seed distribution in the spring of 2011 was more than a request – it is already part of the program.

ACDI-VOCA's deputy director, agronomist Mathieu Lucien, agrees with Sperling. In an email, he told Haiti Grassroots Watch: “distributions every year is not the solution. In [spring, 2010], it was important to quickly boost production of food on a broader level… [but a] quick switch to a longer term approach should quickly follow.”

Part 5 – Seeds in Haiti – Who is in charge?

Geographically speaking, the director of the “Service National Semencier” (SNS or National Seed Service), Emmanuel Prophete, works near the UN “Logistics Base” where Agriculture Cluster meetings take place. And he sometimes attends. But his run-down building and small experimental garden, located behind the crumbling and cracked shell of the Ministry of Agriculture in Damien, are a long way from the multi-million-dollar budgets run by USAID, Oxfam, the FAO and others working in agriculture in Haiti.

Prophete does not appear jealous, or even angry. But maybe a little frustrated, because he is passionate about seeds and how improved seeds and fertilizer can help Haitian farmers increase production. (Prophete defends the Ministry’s decision to accept Monsanto’s give of hybrid maize and vegetable seeds. See Monsanto in Haiti.)

The agronomist has been at the MARDNR for almost 35 years. He's written budgets, gone to conferences, watched politicians make promises, and seen projects come and go. And he's seen Haitian agricultural sector decline.

The agronomist is pleased that farmers have been getting access to improved seed stock, tools and other inputs, through various projects and the emergency aid. The distributions help boost production, but, he notes, “the system is based on a subsidy… You have to ask yourself about the sustainability because if the policy changes one day, where will peasants get seeds?”

Emmanuel Prophete, head of the National Seed Service, in one of the Ministry of Agriculture's fields.

The 2010 emergency seed distributions didn't represent anything new, Prophete noted. In a certain sense, the distributions could be seen as a continuation of a $10.2 million, FAO-MARDNR project in 2008 and 2009 which reached 240,000 families with “quality” seeds from places like Guatemala and which also funded “quality” seed multiplication efforts. On its website, the FAO said the effort was the beginning of “an agricultural renaissance,” and indeed, according to the MARDNR and FAO, “agricultural production rose by 25 percent in the 2009 spring planting season compared with 2008.”

But is it sustainable?

“If you want to talk about sustainability, the [current] approach is not the best. It's for a crisis period. Last year was the earthquake. We are still in the crisis. But sooner or later, these distributions will end… We'll get to a point where, one day, we have a lot of seeds, and then suddenly, when all the NGOs are gone, we won't have any.”

Prophete is in a challenging position. Beginning a few years ago, donors and development organizations finally began to focus more seriously on the seed issue. But today, he and the SNS are exactly where they were before that focus developed: in a tiny office, with a tiny budget and a staff of only two… himself and his assistant.

And so Prophete collaborates. The SNS is ready to assist any effort that helps Haiti's farmers: the FAO, ACDI-VOCA, WINNER… For example, the SNS will collaborate with the new FAO seed project this year, Prophete said, and the MARDNR was one of the big distributors of seed last spring, handing out almost 1,000 MT.

But the SNS is not the lead in the new FAO seed project, nor was it the lead in the multi-million dollar seed distributions. Indeed, Prophete wasn't even aware of the spring distributions announced at the February 8 Cluster meeting until Haiti Grassroots Watch handed him the Excel spreadsheet.

And the SNS doesn't get funding via the Agriculture Cluster projects.

Of the $31,526,150 that went to Agriculture Cluster projects in 2010, the MARDNR received zero, according to UN documents.

Of the $43,087,517 requested for 22 projects for 2011, the MARDNR is listed as the principal recipient on zero of the projects.

Asked about the 2011 Cluster request, Prophete was as pragmatic as he was ecumenical:

“If they get that, it's good for them. If they don't get it, it wouldn't come to Damien, in any case. But if that money can somehow benefit peasants, I am 100 percent in agreement with their request.”

Ending the “emergency, emergency, emergency system”

The MARDNR's five-year investment plan calls for emergency seed distribution for three seasons (meaning, through about January, 2011), but then lays out a medium-term “Access to Inputs and Services” plan. The plan calls for a $2.4 million investment in the SNS, with more investments in other institutions and efforts, in order to build up a self-sufficient, government-regulated, market-driven “quality seed system” in Haiti.

“For the system to be sustainable, it has to be the state budget, the public treasury, that says: 'Here is money for seeds.'… Only by reinforcing of the state structures will the country advance,” Prophete said.

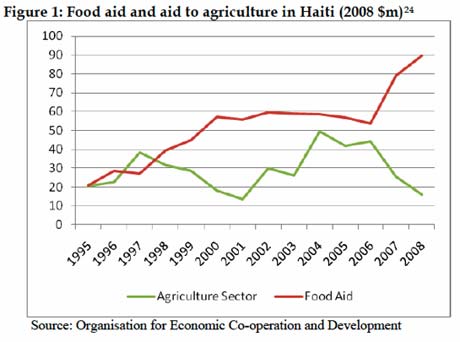

No wonder Prophete feels that way. According to a recent Oxfam report, between 2000 and 2005, only 2.5 percent of development aid went to agriculture, and historically, food aid has trumped agricultural aid.

So far, the MARDNR's medium-term “Access to Inputs and Services” budget, which includes the seed sector improvement, has not been funded, as far as Prophete knows. And he's worried agriculture won't be a priority of the new government.

“So far I have only heard them talk about education,” he said.

The “reconstruction” funding also appears to be largely bypassing agriculture.

Of the $260 million required for agriculture, according to the UN Office of the Special Envoy's “Assistance Tracker,” as of March 19, $186 million has been pledged, but only $24.4 million – only nine percent – had been disbursed.

• If and when those millions are disbursed, will they go to the Ministry of Agriculture and the SNS, and will the state be able to build the “quality seed system” it envisages?

• How much damage might the seed aid be doing?

• Will the Ministry, and the government, enforce legislation and conventions which prohibit the importation of foreign seeds and plants?

• Will the government take on the large landowners and others who have held Haitian farmers hostage since independence, over 200 years ago?

• Will there be an energy plan which renders charcoal, and thus most tree-cutting, obsolete?

• Can a market-driven agricultural sector exist on an uneven regional and international playing field, where some governments subsidize their farmers?

• And will the government take on Washington and the other forces who rammed the neoliberal low tariff scheme down Haiti's throat?

Prophete can't answer those questions or control those decisions, but he does know about seeds.

As he showed off a bean variety he and his colleague have been testing, he said:

“I want to work for sustainability. I think we need to get out of this emergency, emergency, emergency system.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 500 new monthly donors in the next 10 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.