Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

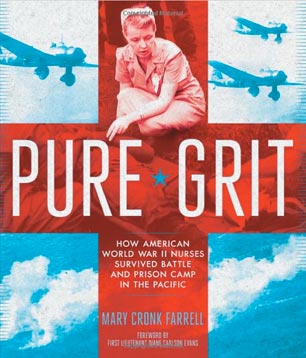

Pure Grit tells an amazing, previously untold, story about 79 American Army and Navy nurses – all of them white females – who were captured by the Japanese during World War II and held as prisoners of war in the Philippines. It’s grisly stuff, and Farrell’s detailed descriptions are vividly grotesque. What’s more, while she celebrates the stamina and sheer audacity of this band of sisters, she also makes clear that putting oneself in harm’s way, as these women did, is a surefire introduction to a bloody, chaotic and disease-ridden hell.

Farrell neither celebrates patriotism nor condemns war. Nonetheless, as the story unfolds, so does the horror.

But let’s start at the beginning, in 1940, when hundreds of American women, most from small towns and rural villages in the US heartland, signed up to serve as military nurses. They did so for the same reasons young men and women enlist today: a shortage of decent jobs at home; the desire to break free from family or community restrains; a need to assert individuality; love of country and yearning to give back; and the mistaken idea that military service will provide fun adventures on Uncle Sam’s dime.

Some of the nurses were stationed in Manila. At first, Farrell writes, the job seemed like a dream come true. “Since the hot, humid weather could be tiring for people from the States, nurses worked only four hours on the day shifts. They rotated through eight-hour shifts in the cooler temperatures overnight.” Even better, she continues, the women lived in near-splendor. “Mahogany fans cooled the rooms, drawing the fragrance of gardenias in through the open windows. Outside, purple bougainvillea and yellow plumeria bloomed. Orchids grew everywhere. … Hired Filipinos did the laundry, cooking and cleaning. A servant often served meals.” Men – pilots, soldiers and sailors who were stationed nearby – frequently came calling.

And then, of course, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the United States entered the war. Suddenly bombs began falling on the Philippine islands, and virtually overnight, the nurses were called to full-time, 24/7, duty. “The bombardment soon filled the hospital with hundreds of wounded and dying men. … The Army nurses had never had any training for combat nursing. Wards overflowed. The wounded lay on the porches, some on litters, some on the ground. Nurses gave shot after shot of morphine – to deaden the men’s pain and quiet their screaming.” Nurses and doctors subsequently had the grim task of separating the patients into groups depending on the severity of their injuries. “The nurses had read about triage in textbooks but had never expected to make these grave choices themselves,” Farrell writes.

As the pounding continued, patients were crammed two to three to a bed. Supplies dwindled. Two weeks later, on December 24, 1941, “the first 25 Army nurses joined doctors and corpsmen in a convoy of buses and military trucks. They headed for Bataan and Army General Hospital Number 1. … They had no idea they were making history as the first group of American Army women ordered into combat.”

One anecdote will serve to illustrate the terror the women must have felt: Before leaving for Bataan, nurse Frances Nash grabbed enough morphine to give each American nurse a lethal dose if they were taken prisoner.

Conditions in Bataan, a hastily built facility, were predictably squalid, and the nurses were reportedly ordered to work 20-hour shifts. Worse, Japanese soldiers surrounded the hospital and nurses’ quarters. Although the soldiers were better behaved than the Americans expected – anticipated sexual assaults never happened, likely the reason that the drugs Nash had squirreled away went unused – they did what they could to make it hard for medical crews to do their jobs. For example, at one point rumors that the Japanese were about to confiscate all medications circulated. In response, the women had to spend their time relabeling valuable anti-malarial medications so that the bottles looked as though they contained far-less-useful soda bicarbonate.

Still, wily tactics aside, the open-air hospital was beyond primitive, and the women had to contend with flies, lizards, maggots, mosquitos and snakes. Sanitation was nonexistent, and beriberi, dengue fever, dysentery and malaria were rampant among patients and nurses. Food, especially protein, was also scarce.

Bad as things were, everything got worse in early April 1942: Filipino-American forces on Bataan surrendered to the Japanese, and all military personnel and hospitalized patients were transferred to the Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor Island. At first, there was enough food for everyone, making it possible for the nurses to care for their wards. It was a short-lived improvement, however, undone once American troops surrendered on May 6. Farrell recounts: “A group of US Army women had never before surrendered to an enemy. … Tearing a large square from a bed sheet, the nurses scrawled at the top, ‘Members of the Army Nurse Corps and Civilian Women Who Were in Malinta Tunnel When Corregidor Fell.’ Sixty-nine women signed their names to leave a record in case they disappeared.”

They were soon moved to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila as prisoners of war. Once again, conditions initially were comfortable. But as Japan’s war losses mounted, shortages became endemic, and the women found themselves starving to death, all of them dropping to between 70 and 80 pounds. Finally, in the winter of 1945, the camp was liberated.

As you might imagine, despite the attention, their re-entry was far from seamless. “America had changed during the war years,” Farrell writes. “Everything moved faster, from the pace people walked, to the cars driving by on the streets. … Despite war rationing of food and gasoline, Americans lived in luxury compared to prison-camp life. The nurses felt alien and isolated. Some faced fresh grief.” Numerous women suffered from what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. Sadly, their condition was of little concern to the government. In fact, the Army wanted to showcase the returning women as quickly as possible, and ordered them to make speeches and sell war bonds. One former POW, Millie Dalton, recalls: “It was terrible because you didn’t want to do it. You were so tired, you just wanted to rest and be with your family.” Another former POW recalls feeling like “an object, sort of a freak.”

To a one, the women simply wanted to put the war behind them and get on with their lives. At the same time, they wanted their due. It was not to be. “Americans wanted heroines to raise their spirits,” Farrell concludes. “But no framework existed in the 1940s for people to understand women who had acted with enduring courage and strength on the battlefield and as prisoners of war – women who had acted like men.” While two of the nurses received Purple Hearts, most got nothing and were even denied veterans’ benefits despite severe physical and psychological ailments.

According to Farrell, nearly 40 years passed before a handful of surviving World War II nurse began to speak out and demand recognition from the US government. By then, many of their former comrades-in-arms had passed on. Although Ronald Reagan honored them at a National POW/MIA Recognition Day in 1983, most felt that this long-overdue gesture was far too little, far too late.

Indeed, by then few were paying attention to events that had transpired decades earlier. Furthermore, while it is easy to look back and condemn those who voluntarily placed themselves in the theater of war – whether because of naiveté or knee-jerk patriotism – the military nurses Farrell describes clearly demonstrated incredible pluck and worked tirelessly to heal the era’s wounded warriors. They certainly did not expect to become POWs or face starvation when they signed up.

The US government treated these veterans badly, using them and then tossing them aside; it’s maddening and shameful. Pure Grit lauds the nurse’s tenacity and courage and assails the sexism that kept them from receiving the honors they deserved. At the same time, it’s impossible to read Pure Grit and not want to do something to stop the suffering that accompanies all wars. As the refrain in Edwin Starr’s 1969 Motown classic reminds us: “War. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.