The fight for a statewide single-payer health-care system has shifted from the Green Mountains to the Rocky Mountains: Colorado citizens are about to put single-payer up for a statewide ballot referendum in the 2016 election. If voters approve, the state constitution will be amended to create a statewide, publicly financed, universal system for the first time in US history.

After a long struggle, Vermont’s proposal for a similar plan died in January 2015, after a decision by the governor to abandon the plan. Green Mountain Care, as it was known, is the closest any state has come to implementing a public health-care system that covers everyone. So the failure was a major disappointment for advocates for social justice everywhere. But the setback didn’t stop activists in states across the country from pursuing similar reforms. Many in these states watched events in Vermont closely – to see what worked and what didn’t and to avoid the pitfalls that proved fatal.

The strategy for reform in Colorado is dramatically different from the one used in Vermont.

Colorado has been especially active, and activists are set to turn in more than 150,000 signatures (about 99,000 are required) to put health reform on the 2016 ballot, said Lyn Gullette, campaign director for ColoradoCareYES. Organizers say they are optimistic that their strategy will succeed where Vermont’s failed – and that when ballots are cast in 2016, public, universal health care may become a reality in Colorado.

Organizer Elaine Grace Dwiter Branjord collects signatures for Colorado Care at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)“We are really excited about this. We have been so heavily invested in the campaign,” Gullette told Truthout. “Of course, we watched events in Vermont closely. There were some things they did that we want to emulate and things we want to do differently.”

Organizer Elaine Grace Dwiter Branjord collects signatures for Colorado Care at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)“We are really excited about this. We have been so heavily invested in the campaign,” Gullette told Truthout. “Of course, we watched events in Vermont closely. There were some things they did that we want to emulate and things we want to do differently.”

Vermont, however, is probably the most progressive state in the union. Its legislature is dominated by Democrats, and its citizens have elected a self-identified socialist as a mayor, a congressman and a senator, repeatedly for decades. How can Colorado – a purple state with a divided legislature – expect to make such a landmark advancement in health-care reform and social democracy?

It is a fair question. The strategy for reform in Colorado, however, is dramatically different from the one used in Vermont. Colorado Care has a chance to succeed for several important reasons: 1) Colorado law allows for citizen’s ballot initiatives, which limits the ability for politicians to intervene; 2) local politicians say the Affordable Care Act’s “state innovation” language is more favorable to Colorado in terms of financing a plan; and 3) organizers have been much more specific in how the plan will be funded, after watching how the ambiguities of Vermont’s plan contributed to its demise.

If all the signatures are validated by the Colorado secretary of state’s office (which could take several months), the question will be decided by Colorado voters, whose judgment on Initiative 20 will have an impact all across the country. It is important for advocates of health-care justice everywhere in the United States to become invested in this campaign.

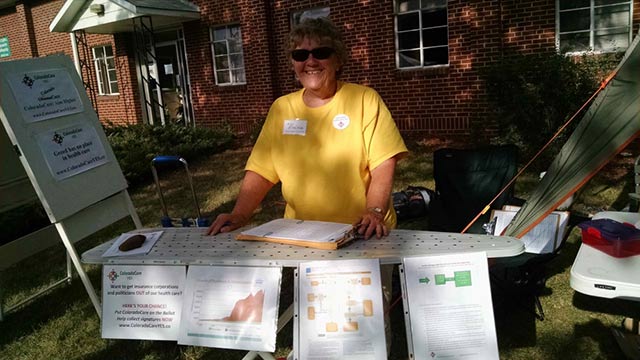

Organizer Eliza Carney works a table at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Organizer Eliza Carney works a table at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Lessons From the Vermont Failure

When Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin abandoned his state’s plan for a single-payer system, it was a major blow to activists in Vermont. Citizens had worked tirelessly for years – and got as close as any state in recent memory to this kind of reform. Shumlin’s betrayal was egregious. In 2010, he won a razor-thin election, in large part by running on a single-payer platform. His campaign ads, still available on YouTube, show him mentioning his goal of a “single-payer” plan as his first bullet point. This support won him key endorsements from doctors, including Dr. Deb Richter, a member of Physicians for a National Health Plan and arguably the most visible single-payer advocate in the state.

Shumlin not only shuttered the plans but also twisted the knife in doing so. In his announcement, he obfuscated his own selfish political calculations and wrongly blamed the plan’s demise on the economics of the issue, citing a danger of tax hikes. Not only did he kill the plan, but he provided ammo to critics of single-payer who continue to perpetuate massive falsehoods about the economics of this reform. “This surrender is all the more remarkable because the Green Mountain People’s Republic is the ideal socialist laboratory,” observed The Wall Street Journal in an editorial celebrating the death of reform in Vermont.

If it becomes law, Colorado Care will be run by trustees who are elected by residents from each of the state’s seven congressional districts.

Shumlin’s rationale was false and disingenuous. In January 2011, Dr. William Hsiao, who was contracted by the state to study the economic costs of the plan, concluded in a report that Vermont would save hundreds of millions of dollars under single-payer. Shumlin’s statement at the time of the report’s release speaks for itself: “It’s clear that moving to a single payer plan, with or without a limited role for private insurers, will save Vermont significant money in health care.”

The actions of Vermont’s governor now place a dark shadow over single-payer advocates everywhere. The national groups that poured into Vermont retreated. The SEIU-funded group Vermont Leads: Single Payer Now shuttered its website; its final word on the subject – a timid note of disappointment – can only be seen on a cached archive. Emails to staffers are bounced back.

“The way Shumlin handled it, he really set the whole movement back nationally,” said Gerald Friedman, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who has analyzed the impacts of single-payer of several states, including Colorado.

Organizer Elaine Branjord at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Organizer Elaine Branjord at NewWestFest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Avoiding the Pitfalls: Colorado’s Strategy for Reform

With the benefit of hindsight, the strategic mistakes made in Vermont are clear enough. The first hint of this was first seen when Vermont passed S.88 into law in May 2011. Overzealous headline writers touted that “Vermont Passes Single-Payer Health Care.” But this was wildly premature. The law is officially described as an “act relating to establishing the framework for publicly financed primary care.” It called for the design of three systems but punted on the financing issue, which politicians would settle on down the road. As we know now, the financing was never settled.

The ambiguity of S.88 was a major flaw in the design of Vermont’s system. Organizers in Colorado took notice, said Irene Aguilar, a state senator who was the legislative sponsor for Colorado Care. Anyone can go online and read all the specifics of Colorado’s plan: the payroll and employer tax rates, the impact on job churn, the impact on seniors, the savings expected for businesses, residents and the government, and so on.

The analysis shows a savings of $6.2 billion in administrative costs, a $4.5 billion reduction in expenses for residents and employers and a population that is 100 percent insured. As of now, there are approximately 603,000 people in Colorado who are uninsured.

“Colorado Care would not be possible without the Affordable Care Act.”

Colorado’s strategy also benefited from its election laws, which allow for a citizens’ ballot initiative – which many states do have. In Vermont, organizers had to work with politicians every step of the way – from ordering studies, to passing preliminary plans, to funding the plan. But politicians can be fickle. Their actions are protean, often guided by political calculations that aim to ensure their political survival and protect their party, as opposed to being primarily guided by their own beliefs and morals.

Colorado and the 25 other states where some form of citizens’ ballot initiatives exists have (to varying degrees) the ability to go around the legislature and propose state laws by collecting signatures and putting binding referendums up for votes. This is an empowering tool for citizens and is as close to direct democracy as it comes in the United States. Conservatives and leftists alike often tout these initiatives when displeased with their state governments. Since Colorado has this system, the 2016 election will be about convincing voters of the merits of publicly financed health care – not state legislators who are constantly pressured by interest groups, donors and lobbyists.

Of course, the extent to which ballot initiatives work varies widely. Citizens in Charge grades all 50 states on their support of these kinds of initiatives. Vermont received a D-, and was spared a lower grade because many citizens do have “local initiative and referendum rights.” Colorado received a C-, downgraded for some restrictions on how signatures can be collected.

Not only does the Colorado state government lack control over whether the law passes, but also it will be limited in its ability to govern the system if it passes. If it becomes law, Colorado Care will be run by trustees who are elected by residents from each of the state’s seven congressional districts.

“Colorado Care would be a cooperative type of business in which every adult resident is a voting member … it will not run by the legislature,” said ColoradoCareYES’s Gullette. “Politicians do not have the ability to run a health-care system … we want to make [Colorado Care] really locally responsive.”

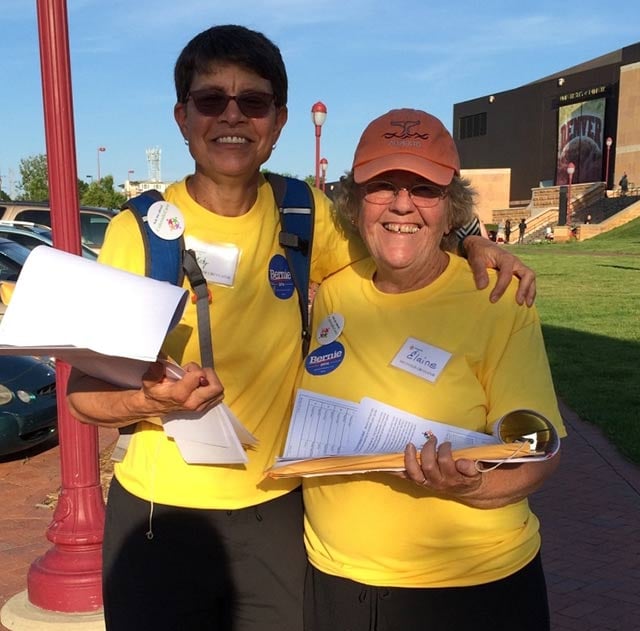

Organizers Katy Kohnen and Elaine Branjord at a Bernie Sanders event in June. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Organizers Katy Kohnen and Elaine Branjord at a Bernie Sanders event in June. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

An Ally in the State House

While the ballot initiative is decided by voters rather than legislators, getting it up for a vote did require some help in the state government. But for years there were no real advocates for single-payer in the Colorado Legislature. This frustrated Dr. Irene Aguilar greatly. When the senator in her district decided to run for mayor, Aguilar ran for the State Senate and in November 2011, she became the ally in the State House she long wished she had.

“For years I couldn’t get anyone to move on the issue,” she said in a phone interview with Truthout. “So I ran for the seat. And I ran to win.”

Advocates welcomed her surprise foray into politics. “She is extremely intelligent and has done so much for the cause,” Gullette said. “She is a doctor, has the right values … she is a tremendous ally.”

With a friend in the legislature, single-payer advocates had a new chest of tools to use: Aguilar could bring the issue to the floor, introduce legislation and provide access to consultants and studies. These resources, now accessible to organizers, proved vital to making the push for Colorado Care a reality.

Organizer Bill Semple collects signatures at a Bernie Sanders event. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Organizer Bill Semple collects signatures at a Bernie Sanders event. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

The Affordable Care Act and State Reform

In 2009 and 2010, when a very public battle over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was taking place, one of the less publicized negotiations was over “state innovation waivers.” This language is crucial to passing a statewide health-care plan as it allows a state to use ACA funds to cover its own system so long as it offers the same (or better) benefits than those mandated by the ACA, and would cover as many (or more) people.

The waivers are not available to states until 2017, which frustrated Vermonters who were trying to push for reform years ago. But the time frame lines up quite well for Colorado Care. More importantly, Aguilar said, is that the waiver is essential to making the financing of the system work.

In fact, Colorado actually receives more money from the federal government under a waiver than Vermont did, Aguilar said. This is because Colorado had more stringent Medicaid eligibility standards than Vermont and required more federal aid to account for the Medicaid expansion under the ACA. It is ironic that Vermont was in some way punished for having a better safety net, but this does mark yet one more area where the two states differ in reform efforts.

The woeful state of politics in Washington is one of the major reasons why single-payer activists have targeted reforms in the states.

Still, there are concerns about how the waivers will work and if the federal government will allow such a potentially transformative reform to take place in a state – especially with the drug and insurance companies dangling carrots in front of legislators during every election. The industry is always among the top campaign donors and in the 2014 campaign cycle, Open Secrets reports, Democrats received 42 percent of their donations.

Another potential obstacle, Friedman said, is how much room the ACA leaves for interpretation. “The language is not very specific,” he said, noting that it is unclear what metrics will be used to determine if plans satisfy requirements. “Will they use projections? Will they be over a 10-year period? A one-year period? We just don’t know.”

Furthermore, this process will be governed by the secretary of health and human services. The selection of the candidate to fill that role will be determined by the winner of the 2016 presidential election and it is not hard to imagine a cabinet member of, say, a Ted Cruz administration, attempting to derail Colorado Care (or any other similar plan) for ideological reasons.

But many are optimistic about the ACA’s role in the fight for statewide reform. In 2010, Dr. William Hsiao told Truthout that the ACA “left a lot of room for state innovation waivers.” Aguilar shares his optimism. “Colorado Care would not be possible without the Affordable Care Act,” she said.

Ken Connell and Randy James collect signatures for Colorado Care at Pridefest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

Ken Connell and Randy James collect signatures for Colorado Care at Pridefest. (Photo: ColoradoCareYES)

National Reform vs. Statewide Reform

Many single-payer advocates across the country are excited to see Sen. Bernie Sanders advocating for a national single-payer system as a presidential candidate in front of millions of people. Sanders’ general argument for the reform is strong: Our country’s “system” of health care – even with the modest improvements of the ACA – is a disgrace.

There are 41 million Americans who are uninsured, many more underinsured and medical bills are the leading cause of bankruptcy in the country. On a financial level, it is unsustainable and wasteful. The United States spends almost 17 percent of its gross domestic product on health care, while the average developed nation spends only 9.3 percent, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The bigger battle will come in 2016.

The US public has long supported public health care. However, it’s unlikely that a single-payer bill will become national law anytime soon, despite the current system’s wasteful inefficiency and inherent cruelty. While a bill proposing a “Medicare for All” system, HR.676, has 53 co-sponsors in the House, there is almost no public support for it in the Senate. Bernie Sanders may well be the only senator to vote for such a plan. When President Obama and a Democratic Congress were pushing for reform in 2010, single-payer advocates weren’t even invited to the table.

The woeful state of politics in Washington is one of the major reasons why single-payer activists have targeted reforms in the states. Canada’s national health system was born from a universal health-care system enacted in one province. Activists hope that when the benefits – both economically and morally – are seen, other states will follow and the dominoes will fall.

Richard Gottfried, an assembly member in New York, recently helped pass a single-payer bill in the New York State Assembly. But the State Senate in New York is far more conservative, and the only way to pass a similar bill in that body would be to elect new legislators. Any state’s path toward a single-payer system will be easier once one state can prove the benefits of public health care.

“If people knew one of the issues on the line was getting health care for everyone, without all these barriers, it could have a real impact [on elections],” Gottfried said in an interview with Truthout. “A lot of people tell me they think single-payer is good policy, but just isn’t politically possible. We need to show that this isn’t the case.”

Limits to Statewide Reform

But there are downsides to statewide reform. While “single-payer” has become (and is used in this article as) a catchall for publicly financed plans that cover everyone, the reality is that even if Colorado Care passes, there will technically be more than one payer. Seniors and veterans in the state, for instance, will still be insured through a different payer. True single-payer is not possible in just one state because of the relationship between the states and the federal government.

“When we talk about ‘single-payer’ in the states, what you really are talking about is having just three or four payers … instead of countless payers,” Friedman said.

The principles are the same: cover everyone through the government and save money by eliminating administrative waste, corporate profits and monopoly pricing by hospitals. But the benefits of single-payer care work best on a national level. Federal reform would maximize savings thanks to a wider risk pool, economies of scale and the fact that it can be accomplished by expanding Medicare to the entire population.

Some single-payer advocates are skeptical of Colorado Care. Donna Smith, executive director of Health Care for All Colorado, is quick to point out that Colorado Care is not a true single-payer plan. “Though we understand that political feasibility has played a heavy role in development of this health reform plan,” Smith told Truthout, “we continue to exert a critical ‘leftward pull’ on the campaign as we point out the differences between single-payer and Colorado Care.”

The Health Care for All Colorado website doesn’t mention the signature campaign, and Smith says the prospect for a coalition between her organization and ColoradoCareYES “remains unknown.”

These types of internal conflicts between advocates of health-care reform are not new on the left. Labor reporter Steve Early reported in 2012 that some single-payer activists viewed the SEIU’s involvement as a potential “Trojan horse” that could “weaken Vermont’s movement.” Physicians for a National Health Plan had mixed feelings about Vermont’s “diluted” plan and argued it was a “misnomer” to label it as single-payer. The organization has not yet commented on Colorado Care.

The Battle to Come

While some on the left will continue to argue over strategy and details, the bigger battle will come in 2016. Organizers estimate opponents from across the country could devote as much as $20 million to encourage “no” votes. These critics will try and mislead voters with myths about how single-payer is too expensive. Supporters of single-payer health care will need to educate the public to win this argument.

To succeed in the long-term goal of establishing a national, single-payer bill that covers the entire country, a state will need to break this ground first. It didn’t happen in Vermont, but it will happen eventually. And Colorado’s chances of making single-payer work appear as good as any.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.