Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

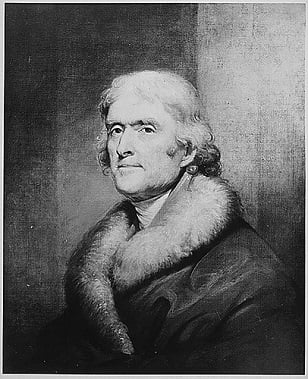

Marion Doss / Flickr)” width=”308″ height=”379″ />Thomas Jefferson. Copy of painting by Rembrandt Peale, circa 1805. Still Picture Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park. (Image: Marion Doss / Flickr)Americans are proud that their Declaration of Independence was also a declaration of universal rights. But the hard truth is that, in 1776, the words were mere propaganda cloaking the fact that a third of the signers were slaveholders, including the famous author, Thomas Jefferson, as Robert Parry recalls.

Marion Doss / Flickr)” width=”308″ height=”379″ />Thomas Jefferson. Copy of painting by Rembrandt Peale, circa 1805. Still Picture Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park. (Image: Marion Doss / Flickr)Americans are proud that their Declaration of Independence was also a declaration of universal rights. But the hard truth is that, in 1776, the words were mere propaganda cloaking the fact that a third of the signers were slaveholders, including the famous author, Thomas Jefferson, as Robert Parry recalls.

Thomas Jefferson is admired for his elegant prose in the Declaration of Independence, but he was a world-class hypocrite. He wrote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” – but he didn’t really believe any of that.

In his thoroughly repugnant book, Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson even engaged in the pseudo-science of measuring the skulls of African-Americans to prove that not all men were created equal. Some of Jefferson’s white supremacy nonsense survives to the present day in the views of unreconstructed segregationists.

Because of his racism – and his undeniable political skills – Jefferson also ranks among the Founders as perhaps the most responsible for putting the United States on course for the Civil War. In the years after the Constitution was ratified, he pushed a highly constrained view of federal power, supporting the interests of white Southern plantation owners who feared that a strong central government would eventually doom slavery.

To promote that position, Jefferson injected a nasty factionalism that demonized George Washington’s Federalist allies, especially Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, in the 1790s. Hamilton, Adams and Washington believed that a vibrant central government was crucial for the nation’s development.

However, Jefferson and other Southern slaveholders saw an effective central government as an existential threat to slavery. Thus, they ramped up their angry insistence of “states’ rights” and concocted an extra-constitutional theory about the power of the states to “nullify” federal law.

Jefferson was the driving force in this movement, creating what became known as the Virginia Dynasty, a string of three consecutive two-term U.S. presidents from Virginia, starting with Jefferson in 1801 and continuing through James Madison and ending with James Monroe in 1825. By then, slavery’s roots had dug down even deeper across the South and spread into new states to the west.

It would take the bloodbath of the Civil War to finally pull slavery out of the soil of the South, but Jefferson’s weed-like political legacy would keep resurfacing, first after Reconstruction with the South’s reassertion of “states’ rights” and white supremacy. The South again would resist federal authority and repress blacks under Jim Crow laws and segregation.

Even today’s anti-government extremism from the likes of the Tea Party and “libertarians” can be traced back to Jefferson, a common thread from the days when Jefferson’s pro-slavery “nullificationists” tied up the pre-Civil War Congress to today’s anti-government extremism that has made Congress again a laughingstock of dysfunction.

Fearing Slave Rebellion

So, as Americans admire Jefferson’s soaring words – first read to the American people on July 4, 1776 – they shouldn’t forget that Jefferson and many of his fellow delegates at the Continental Congress considered their African-American slaves as mere investments, albeit potentially dangerous ones who needed to be kept in line with whips, guns and nooses.

A major impetus toward the Revolution in Virginia came when the tough-minded Royal Governor, the Earl of Dunmore, responded to colonial insults and insubordination in 1775 by threatening to “declare freedom to the slaves.” This perceived British encouragement of slave rebellions scared Virginia’s white aristocracy and created a financial incentive for plantation owners to join the drive toward independence, much as Britain’s blockade of Boston’s port did for the colonial ruling class of Massachusetts.

Some of Jefferson’s modern defenders argue that he shouldn’t be criticized too harshly for his hypocrisy on slavery, saying he should be judged by the standards of his time. But Jefferson – more than most people today – knew the horrors and degradations of slavery. He made that clear in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence when he included a segment blaming the King of England for the slave trade:

“He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium ofinfidelpowers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold.

“He has prostituted his negative [his veto] for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce; and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die. He is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of whichhehas deprived them, by murdering the people for whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against thelibertiesof one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against thelivesof another.”

This section was largely deleted by slaveholding delegates of the Continental Congress – only the phrase “He has excited domestic Insurrections among us” survived – but Jefferson’s attempt to place the blame for slavery on the King, rather than on the colonists who owned slaves, reveals that he was well aware of the evils involved in the slave industry. Ultimately, a third of the signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves, including Jefferson.

Fighting the Federalists

After the Revolutionary War was won, the country floundered under the Articles of Confederation, which declared the states “sovereign” and “independent.” To save the nation’s fragile independence, George Washington and his then-protégé James Madison devised a new Constitution in 1787 that concentrated power in the central government.

However, this major change was fiercely opposed by key Southerners, such as Virginia’s Patrick Henry and George Mason, who warned that the federal government would eventually come under the control of the North and would demand the end of slavery – thus intruding on the “rights” of white Virginians to own black slaves. Despite these warnings, the Constitution won ratification, albeit narrowly in Virginia. [For details, see Consortiumnews.com’s “The Right’s Dubious Claim to Madison.”]

During this period of the writing and ratification of the Constitution, Jefferson was outside the country serving as the U.S. representative to France. His input into the debate over the Constitution was limited to several letters to Madison in which Jefferson criticized the dramatic power shift but did not advocate rejection.

When Jefferson returned to the United States in 1789 – and then served as President Washington’s Secretary of State – he grew worried about Virginia’s interests within the new constitutional framework and became harshly critical of Treasury Secretary Hamilton’s ambitious plans for creating a financial system and building the nation.

The charismatic Jefferson also began pulling his Virginia neighbor Madison out of Washington’s orbit and into his own, a shift in allegiance that caught Washington and Hamilton by surprise. Soon, with Jefferson secretly funding newspaper attacks on the Federalists — and them returning the favor — the young United States began descending into the bitter factionalism that Washington had feared.

A gifted wordsmith and impressive intellectual, Jefferson also proved adept at playing these power games as he shaped his small-government political faction into the Democratic-Republican Party. In 1800, from his perch as Vice President, Jefferson succeeded in ousting President John Adams amid such acrimony that it left lasting scars in the two men’s relationship which stretched back to Adams recruiting Jefferson to write the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson considered his election in 1800 the “Second American Revolution” in that it pushed back against the strong nationalism of the Federalists and replaced it with a new constitutional interpretation that emphasized “states’ rights.”

Jefferson succeeded in selling his movement as the essence of democracy, relying on industrious small farmers and their common wisdom. But his real political base was the aristocracy of Southern plantation owners. It was their vast investment in slavery that was protected most by Jefferson’s resistance to an activist central government.

Through the first quarter of the Nineteenth Century, with the federal government constrained and with Virginians at the helm, the cataclysmic fear of Jefferson’s fellow slaveholders – Patrick Henry and George Mason – could be deferred; a weak federal government would not soon infringe on their “liberty” to own other humans.

The ‘Black Jacobins’

But fear of slave rebellions was never too far beneath the surface of Jefferson’s thinking, coloring his attitudes toward a slave revolt in the French colony of St. Domingue (today’s Haiti). There, African slaves took seriously the Jacobins’ cry of “liberty, equality and fraternity.” After their demands for freedom were rebuffed and the brutal French plantation system continued, violent slave uprisings followed.

Hundreds of white plantation owners were slain as the rebels overran the colony. A self-educated slave named Toussaint L’Ouverture emerged as the revolution’s leader, demonstrating skills on the battlefield and in the complexities of politics.

Despite the atrocities committed by both sides of the conflict, the rebels – known as the “Black Jacobins” – gained the sympathy of the American Federalists. L’Ouverture negotiated friendly relations with the Federalist administration under President John Adams. Alexander Hamilton, a native of the Caribbean himself, helped L’Ouverture draft a constitution.

But events in Paris and Washington soon conspired to undo the promise of Haiti’s emancipation from slavery. Despite the Federalist sympathies, many American slave-owners, including Jefferson, feared that slave uprisings might spread northward. “If something is not done, and soon done,” Jefferson wrote in 1797, “we shall be the murderers of our own children.”

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the chaos and excesses of the French Revolution led to the ascendance of Napoleon Bonaparte, a brilliant and vain military commander possessed of legendary ambition. As he expanded his power across Europe, Napoleon also dreamed of rebuilding a French empire in the Americas.

In 1801, Jefferson became the third President of the United States – and his interests at least temporarily aligned with Napoleon’s. The French dictator wanted to restore French control of St. Domingue and Jefferson wanted to see the slave rebellion crushed.

President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison collaborated with Napoleon through secret diplomatic channels. Napoleon asked Jefferson if the United States would help a French army traveling by sea to St. Domingue. Jefferson replied that “nothing will be easier than to furnish your army and fleet with everything and reduce Toussaint [L’Ouverture] to starvation.”

But Napoleon had a secret second phase of his plan that he didn’t share with Jefferson. Once the French army had subdued L’Ouverture and his rebel force, Napoleon intended to advance to the North American mainland, basing a new French empire in New Orleans and settling the vast territory west of the Mississippi River.

Stopping Napoleon

In 1802, the French expeditionary force achieved initial success against the slave army, driving L’Ouverture’s forces back into the mountains. But, as they retreated, the ex-slaves torched the cities and the plantations, destroying the colony’s once-thriving economic infrastructure. L’Ouverture, hoping to bring the war to an end, accepted Napoleon’s promise of a negotiated settlement that would ban future slavery in the country. As part of the agreement, L’Ouverture turned himself in.

But Napoleon broke his word. Jealous and contemptuous of L’Ouverture, who was regarded by some admirers as a general with skills rivaling Napoleon’s, the French dictator had L’Ouverture shipped in chains back to Europe where he was mistreated and died in prison.

Infuriated by the betrayal, L’Ouverture’s young generals resumed the war with a vengeance. In the months that followed, the French army – already decimated by disease – was overwhelmed by a fierce enemy fighting in familiar terrain and determined not to be put back into slavery.

Napoleon sent a second French army, but it too was destroyed. Though the famed general had conquered much of Europe, he lost 24,000 men, including some of his best troops, in St. Domingue before abandoning his campaign. The death toll among the ex-slaves was much higher, but they had prevailed, albeit over a devastated land.

By 1803, a frustrated Napoleon – denied his foothold in the New World – agreed to sell New Orleans and the Louisiana territories to Jefferson, a negotiation handled by Madison that ironically required just the sort of expansive interpretation of federal powers that the Jeffersonians ordinarily disdained.

However, a greater irony was that the Louisiana Purchase, which opened the heart of the present United States to American settlement and is regarded as possibly Jefferson’s greatest achievement as president, had been made possible despite Jefferson’s misguided – and racist – collaboration with Napoleon.

“By their long and bitter struggle for independence, St. Domingue’s blacks were instrumental in allowing the United States to more than double the size of its territory,” wrote Stanford University professor John Chester Miller in his book, The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery. But, Miller observed, “the decisive contribution made by the black freedom fighters … went almost unnoticed by the Jeffersonian administration.”

Without L’Ouverture’s leadership, the island nation fell into a downward spiral. In 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the radical slave leader who had replaced L’Ouverture, formally declared the nation’s independence and returned it to its original Indian name, Haiti.

A year later, apparently fearing a return of the French, Dessalines ordered the massacre of the remaining French whites on the island. Jefferson reacted to the bloodshed by imposing a stiff economic embargo on Haiti. In 1806, Dessalines himself was brutally assassinated, touching off a cycle of political violence that would haunt Haiti for the next two centuries.

Hand-Wringing over Slavery

On a personal level, Jefferson might occasionally wring his hands about the evils of slavery and express his earnest wish that something could be done. But he also viewed his slaves as investments. He considered his child-bearing female slaves particularly valuable because they could boost his “capital” via reproduction.

“I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm,” Jefferson remarked. “What she produces is an addition to the capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption.”

Though considering blacks inferior to whites and rejecting the possibility that free blacks could live peaceably with whites, Jefferson reputedly bedded one of his teenage slave girls, Sally Hemings.

Jefferson’s many apologists either deny the evidence of this sexual relationship or they insist it was consensual, amounting to something like a historic love story. Some Jefferson apologists also excuse his failure to free his slaves in his will – as George Washington and some other Founders did – because of his financial difficulties. Jefferson only allowed a few slaves from the Hemings family to go free.

Jefferson’s defenders also whitewash much of his political legacy, arguing that “Jeffersonian democracy” was the paragon of liberty, with its supposed reliance on the simple wisdom of hardworking family farmers. But the hypocrisy of “Jeffersonian democracy” was largely the same as the hypocrisy that pervaded the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party was controlled by slave-owning elites, not common farmers and surely not citizens who were serious about setting African-Americans free. Indeed, Jefferson’s political promotion of states’ rights, including “nullification” of federal law, helped set the stage for Southern secession after Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860 as an anti-slavery candidate.

Yet, even after the bloody Civil War, many Southern whites continued to embrace Jefferson’s political hostility to a strong central government, leading to the decades of Jim Crow repression of blacks and surviving to the present day with the racism that bubbles just beneath the surface of the Tea Party.

Virginian First

Arguably, Jefferson’s greatest weakness as a national leader – and why modern Americans should view his legacy with particular skepticism – is that he was a Virginian first, an American second. Like many of his contemporaries, he grew up considering Virginia his country, just as many Bostonians saw themselves primarily as citizens of Massachusetts.

Some colonial leaders, especially George Washington, overcame their parochial interests and came to see themselves as Americans first. For Washington and his aide-de-camp Alexander Hamilton, that transformation was aided by their involvement in fighting up and down the length of the nation. But Jefferson was not a soldier and spent most of the war in Virginia.

As historians Andrew Burstein and Nancy Isenberg note in their 2010 bookMadison and Jefferson,Jefferson – and his later ally Madison – were, first and foremost, politicians representing the interests of their constituencies in Virginia.

“It is hard for most to think of Madison and Jefferson and admit that they were Virginians first, Americans second,” Burstein and Isenberg note. “But this fact seems beyond dispute. Virginians felt they had to act to protect the interests of the Old Dominion, or else, before long, they would become marginalized by a northern-dominated economy.

“Virginians who thought in terms of the profit to be reaped in land were often reluctant to invest in manufacturing enterprises. The real tragedy is that they chose to speculate in slaves rather than in textile factories and iron works. … And so as Virginians tied their fortunes to the land, they failed to extricate themselves from a way of life that was limited in outlook and produced only resistance to economic development.”

So, while it’s understandable why Americans would celebrate Thomas Jefferson’s famous words in the Declaration of Independence, they should not forget the history. Those noble words about the “self-evident” truths – that “all men are created equal” endowed with “unalienable Rights” – were simply propaganda in 1776. They were given substance only by a long struggle against the political machinations of, among others, their author.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $50,000 in the next 9 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.