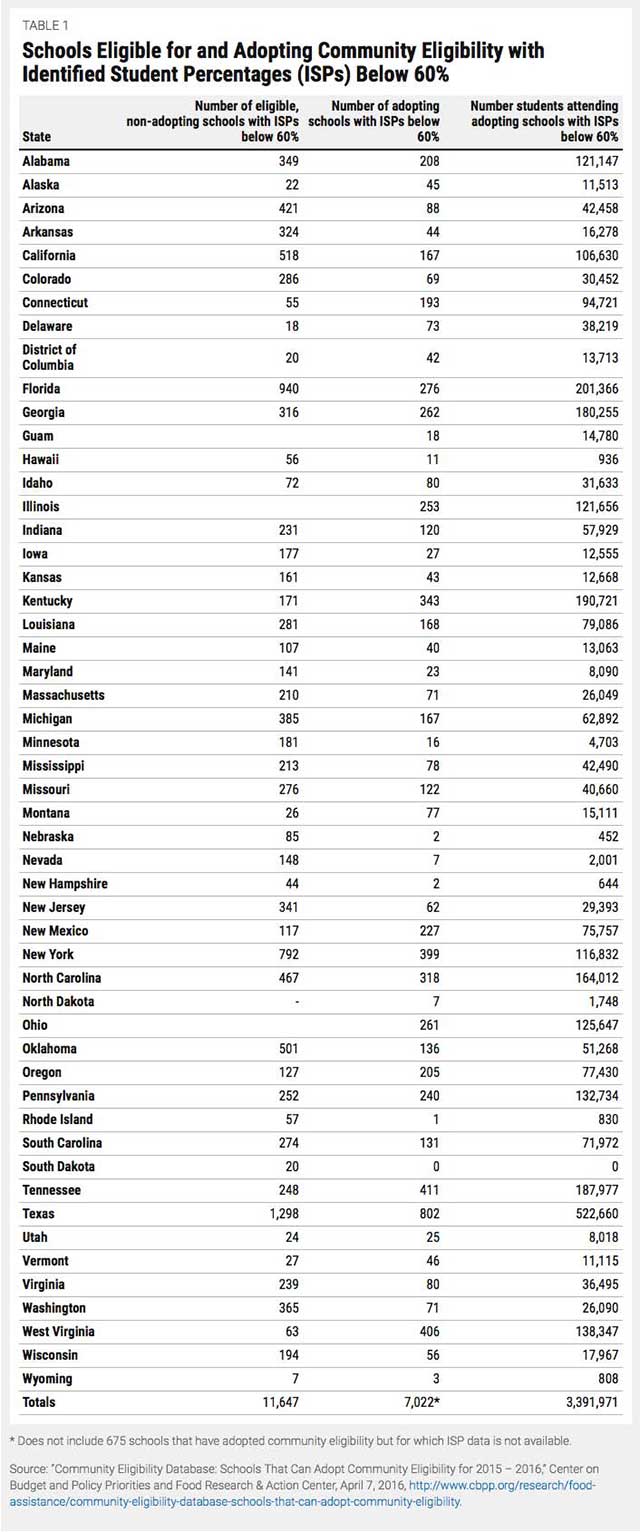

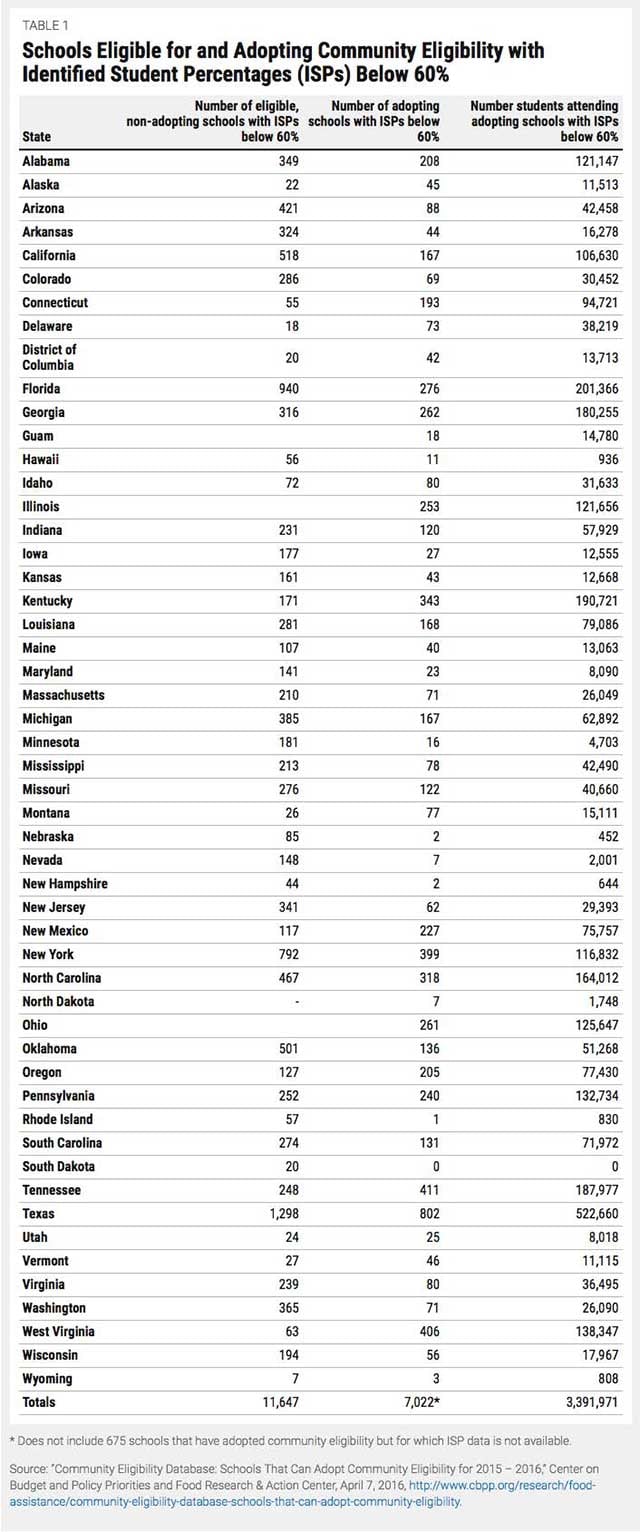

A discussion draft of a child nutrition reauthorization bill that the House Education and Workforce Committee may soon consider includes a provision that would severely restrict schools’ eligibility for community eligibility, an option within the national school lunch and breakfast programs allowing high-poverty schools to provide meals at no charge to all students.[1] If this proposal becomes law, 7,022 schools now using community eligibility to simplify their meal programs and improve access for low-income students would have to reinstate applications and return to monitoring eligibility in the lunch line within two years.[2] These schools serve nearly 3.4 million students. Another 11,647, schools that qualify for community eligibility but have not yet adopted it would lose eligibility.

Policymakers enacted community eligibility in 2010 legislation that received widespread bipartisan support. Eligible schools meet a stringent threshold and are located in some of the nation’s poorest communities, including urban school districts like Baltimore, Chicago, and Detroit as well as rural areas of Kentucky, Montana, and West Virginia, where nearly all students qualify for free or reduced-price school meals.[3] The option was phased in a few states at a time and is now available to eligible school districts nationwide.

In the 2015–2016 school year, its second year of nationwide availability, more than 18,000 high-poverty schools in nearly 3,000 school districts across the country adopted community eligibility.[4] These schools, which serve more than 8.5 million children, represent just over half of all eligible schools, a strikingly high take-up rate for such a new federal option.

Community eligibility’s popularity in its first two years of nationwide implementation speaks to schools’ desire to improve access to healthy meals while reducing red tape, as well as to the option’s sound design. Community eligibility offers several benefits, including:

-

Simplifying administration of the school meal programs so that high-poverty schools can shift resources from paperwork to higher-quality meals or other educational priorities.

-

Improving access to nutritious breakfasts and lunches for low-income students by eliminating the stigma that sometimes accompanies free meals; increased meal participation, in turn, improves student achievement, diets, and behavior.

Growing up in a high-poverty neighborhood can have lasting effects on a child’s growth and development, even if the family itself is not low-income.[5] Access to healthy meals at home and school can help children overcome some of the negative consequences of poverty and food insecurity. Yet the proposal would eliminate the option of community eligibility for thousands of schools serving some of our highest-poverty communities, imposing more paperwork and administrative burdens on under-resourced schools.

Which Schools Qualify for Community Eligibility?

Under federal law, certain students are automatically enrolled for free meals without an application because they are at special risk for food insecurity and other consequences of living in poverty. They include: students in households participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance program, or the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), as well as students who are homeless, migrant, runaway, in Head Start, or in foster care.

Under community eligibility, these especially vulnerable students who enrolled without an application are known as “identified students.” A school (or group of schools) qualifies for community eligibility based on its Identified Student Percentage (ISP), which is determined by dividing its number of identified students by its total enrollment. Schools with an ISP of 40 percent or greater can adopt community eligibility.

Identified students are only a subset of those who would qualify for free or reduced-price meals if the school collected school meal applications. Schools eligible for community eligibility typically have a much higher percentage of low-income students than their ISP, as explained later in this report.

Community eligibility also simplifies schools’ reimbursements for meals served. For schools implementing community eligibility, the reimbursements are based on the school’s ISP. A school’s ISP is multiplied by 1.6 to approximate the share of students that would receive free or reduced-price meals if the school collected meal applications; the resulting percentage is the share of meals that are reimbursed at the highest (free) federal reimbursement rate, while the remaining meals are reimbursed at the lowest (paid) rate.[6]

Thus, even though all meals are served at no charge to students, schools are not reimbursed at the highest rate for all meals. The higher a school’s poverty level, the greater the share of its meals that are reimbursed at the highest rate. Schools must cover the cost of the remaining meals with administrative savings, economies of scale, or non-federal funds.

Proposal Would Impose Paperwork on Thousands of High-Poverty Schools

The proposal would limit community eligibility to schools or groups of schools with ISPs of 60 percent or more, rather than the current threshold of 40 percent. The schools that would no longer qualify for community eligibility serve predominantly low-income students in some of our highest-poverty communities.

As noted above, identified students are only a subset of students who qualify for free or reduced-price meals. Schools in which 40 percent to 60 percent of students are identified as automatically eligible for free meals typically have 64 percent to 96 percent of their students approved for free or reduced-price meals. (This is because some children don’t participate in one of the programs that confer automatic eligibility, were missed in the data matching process used to identify such students, or are eligible for reduced-price meals.) And, in schools with such high concentrations of poverty, students who don’tqualify for free or reduced-price meals are typically not much better off than those who do qualify.

High-poverty neighborhoods, which can be violent, stressful, and environmentally hazardous, can impair children’s cognitive development, school performance, mental health, and long-term physical health — even if the family itself is not low-income.[7] For school districts with high-poverty schools, adopting community eligibility can improve access to school meals and help children perform better in school. Children experiencing hunger have been found to have lower math scores and be more likely to repeat a grade; teens experiencing hunger are more likely to have been suspended from school and have difficulty getting along with other children.[8] Meanwhile, educators report that children who eat breakfast at school are more likely to arrive at school on time, behave, and be attentive in class.[9]

Nationwide, 7,022 schools that have adopted community eligibility have ISPs at or above 40 percent but below 60 percent.[10] The proposal would have an especially profound impact in states with a high take-up rate of community eligibility. More than one-third of the affected schools are located in just five states: Kentucky, New York, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. In addition, 11,647 schools with ISPs at or above 40 percent but below 60 percent have not yet adopted community eligibility and would lose the option. Table 1 shows the number of eligible and adopting schools in each state that would be affected by the proposal.

Examples of community eligibility schools that would have to reinstate paper applications under the House bill include:[11]

-

Alabama: Some 87 schools in Mobile serving about 57,400 students and 55 schools in Montgomery serving about 31,400 students. Child poverty is particularly high in Alabama, where more than one-third of children receive SNAP and more than one-quarter of children live in poverty.

-

Arizona: Six schools in Tuba City, located on the Navajo Nation, serving about 1,500 students. Before they adopted community eligibility, 99 percent of their students were approved for free or reduced-price meals. (Their ISP likely doesn’t capture their level of poverty due to issues with matching student enrollment data with SNAP data.) Also, some 29 schools in the Washington Elementary School District serving about 36,000 students. Before they adopted community eligibility, 85 percent of their students were approved for free or reduced-price meals.

-

Kansas: Some 23 elementary schools in the Kansas City public school system serving about 8,700 students. Before they adopted community eligibility, 90 percent of their students were approved for free or reduced-price meals.

-

Kentucky: The primary, intermediate, middle, and high schools in Greensburg, a city with a population of just under 3,000 and a median income of $24,104.[12] Before they adopted community eligibility, 63 percent of their students were approved for free or reduced-price meals.

-

Louisiana: Some 80 schools in East Baton Rouge serving more than 40,000 students. In Louisiana, 36 percent of children receive SNAP and 28 percent of children live in poverty.

-

North Carolina: The elementary and middle school in Andrews, a town of just under 2,000 in western North Carolina with a median income of $23,594. Before these schools adopted community eligibility, 72 percent of their students were approved for free or reduced-price meals.

-

Oklahoma: Some 53 schools in Oklahoma City serving about 27,000 students as well as the elementary, middle and high schools in Hugo, a town with a population of about 5,300 and an median income of $21,267. More than one-fourth of children in Oklahoma receive SNAP.

-

Pennsylvania: Some 47 schools operated by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia serving about 12,700 students.

-

Tennessee: Some 53 schools in Knox County serving about 23,500 students. More than one-third of children in Tennessee receive SNAP benefits and more than one-quarter of children live in poverty.

-

Texas: Some 802 schools in Texas, including 222 schools in Dallas serving nearly 160,000 students, 57 schools in the Aldine Independent School District serving more than 52,000 students, 49 schools in the San Antonio’s Northside Independent School District serving more than 37,000 students, 31 schools in Corpus Christi serving 17,000 students, and 29 schools in Harlingen serving more than 18,000 students.

-

West Virginia: Some 17 schools in Fayette County, whose population is just over 46,000 and median income is just under $35,000, and some 55 schools in the Kanawha County Public School District, the state’s largest school system, serving over 28,000 students. In West Virginia, 35 percent of children receive SNAP and one-fourth of children live in poverty.

Conclusion

Community eligibility enables schools to deliver, with minimal red tape, a critical benefit that can have lasting positive impacts for children in high-poverty neighborhoods. Severely limiting eligibility for the option would impose burdens on schools that already struggle to educate children despite limited resources and the additional hurdles posed by operating in a high-poverty neighborhood. With community eligibility only in its second year of nationwide implementation, its benefits are just beginning to ripple through schools and low-income communities. Policymakers should leave this option alone and give thousands of schools and the children they serve a better chance to succeed.

School Administrators Laud Community Eligibility

Eliminating community eligibility for schools in high-poverty neighborhoods would likely make it harder for high-poverty schools to feed and educate their students. School administrators that have adopted community eligibility explain its appeal:

-

“Families, teachers, and administrators throughout the Commonwealth are already seeing the benefits that come with ensuring our children are fed and ready to learn. We cannot expect our students to get the education or the skills they deserve if they aren’t receiving the nutrition they need.” — Anne Holton, Virginia Secretary of Education [a]

-

“This program will have a direct benefit on students in the classroom because teachers know that students who are hungry or have not had breakfast have difficulty concentrating on their schoolwork. . . . It will also benefit those parents who, in the past, have struggled to provide the money for their child’s meals. This definitely is a win for our students, for their parents and for our district as a whole.” — Bill Redwine, chair of Rowan County, Kentucky, board of education [b]

-

“Studies have shown that children who receive proper nutrition perform better in school. . . . Many of our families live below the poverty line. Even those that don’t, may skip meals to save money. This will ensure learning won’t suffer because a student is hungry at school.” — Margaret Allen, superintendent of Montgomery, Alabama schools [c]

-

“Being able to eat a nutritious meal during the day helps the students learn — students that eat during the day are more likely to pay attention because they are not worried about being hungry.” — Kim Hall, director of child nutrition services, Muskogee, Oklahoma, public schools [d]

-

“For years we’ve been working with parents, trying to fill out a very difficult form to show that their children qualify for a free or reduced lunch. There’s always been some way for students to know who was on free or reduced lunch and those that were not and there was a stigma attached to that. That’s now completely removed. We will be able to serve lunch to students with everyone being the same.” — Pam Smith, child nutrition director of Lenoir County, North Carolina [e]

a. Willliam Lambers, “Free breakfast, lunch plan a hit in Virginia,” The Examiner, October 28, 2015.

b. “Free meals for elementary, preschool, BDA students,” The Morehead News, June 13, 2014.

c. Kym Klass, “MPS students to receive free lunches, breakfast next school year,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 11, 2014.

d. Cathy Spaulding, “Breakfast, lunch free at 7 MPS schools,” Muskogee Phoenix, August 13, 2014.

e. Noah Clark, “Free lunch for all Lenoir County students,” Kinston.com, May 7, 2014.

End Notes

[1] A copy of the discussion draft is available here.

[2] Some of these schools might be able to continue using community eligibility if their school district groups them with higher-poverty schools. A list of the schools that would be affected is available here.

[3] This paper uses the term “school districts” to refer to Local Educational Agencies.

[4] This paper draws heavily on data gathered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, CBPP, and the Food Research & Action Center published in “Community Eligibility Database: Schools That Can Adopt Community Eligibility for 2015 – 2016,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Food Research & Action Center, April 7, 2016, as well as discussions of community eligibility in Becca Segal et al., “Community Eligibility Adoption Rises for the 2015–2016 School Year, Increasing Access to School Meals,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Food Research & Action Center, April 7, 2016.

[5] See Barbara Sard and Douglas Rice, “Creating Opportunity for Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 15, 2014.

[6] The 1.6 multiplier was derived from analyses indicating that for every ten students who were approved for free school meals without an application, six more were approved for free or reduced-price meals based on an application.

[7] See Sard and Rice.

[8] Katherine Alaimo, Christine M. Olson, and Edward A. Frongillo, Jr. “Food Insufficiency and American School-Aged Children’s Cognitive, Academic, and Psychosocial Development,” Pediatrics 2001, 108(1): 44-53.

[9] J. Michael Murphy, “Breakfast and Learning: An Updated Review,” Journal of Current Nutrition and Food Science 2007, 3(1): 3-36.

[10] This figure does not include 675 schools that have adopted community eligibility but for which ISP data is not available.

[11] The proposal would not eliminate the option to group schools with ISPs below 60 percent with other schools so that the ISP for the group as a whole exceeds 60 percent. These examples are based on the ISPs of the schools themselves or the group in which they are currently participating and are drawn from “Community Eligibility Database: Take Up of Community Eligibility During the 2014-2015 School Year,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 25, 2015, and “Community Eligibility Database: Schools That Can Adopt Community Eligibility for 2015 – 2016,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Food Research & Action Center, April 7, 2016. Percentages of students approved for free or reduced-price meals were calculated based on data published in the U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics’ Common Core of Data. Median incomes were obtained from U.S. Census Bureau, “2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates,” factfinder.census.gov.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $47,000 in the next 8 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.