Part of the Series

Moyers and Company

The vast chasm between the richest one percent of Americans and everyone else continues to widen, and researchers have found that when you factor race into the equation, the economic gap is even more pronounced.

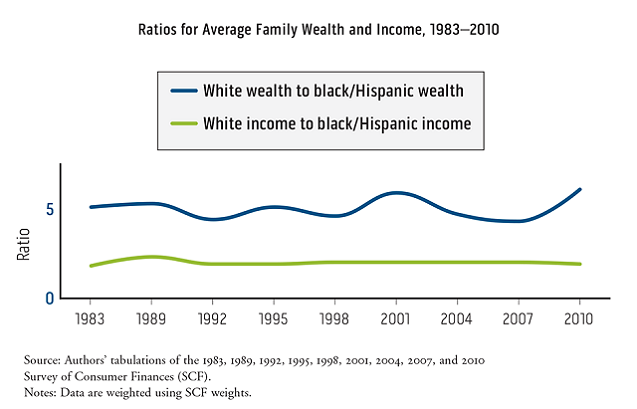

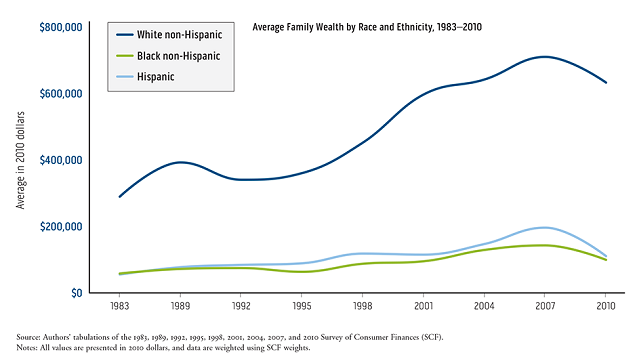

A recent Urban Institute report finds that the racial wealth gap — measured as the difference in wealth accumulated by white Americans and black and Latino Americans — is the largest it has ever been since the Federal Reserve started tracking it. In 1983, for every dollar held by the average black or Latino family, the average white family had five. In the aftermath of the financial meltdown and the Great Recession that figure today has increased to six dollars. The figures for the median post-recession family — a measure less skewed by America’s handful of superrich — are even further apart: in 2010, for every dollar held by the median black or Latino family, the median white family had eight.

Credit: Urban Institute.

Credit: Urban Institute.

One thing that’s remarkable about these statistics is that the racial wealth gap is three times greater than the racial income gap. In other words, white people not only have higher incomes, but they are also better positioned to retain that income and build it. “Such great wealth disparities help explain why many middle-income blacks and Hispanics haven’t seen much improvement in their relative economic status and, in fact, are at greater risk of sliding backwards,” the researchers who compiled the Urban Institute study note.

Credit: Urban Institute.

Credit: Urban Institute.

This is part of the larger trend toward inequality. The richest 20 percent of families saw their wealth increase by nearly 120 percent since the early ’80s, while the poorest 20 percent of Americans saw their wealth decrease over the same period.

Another dimension of the racial wealth gap is that it increases over the course of a lifetime, so that elderly black and Latino Americans are in a significantly worse place than white senior citizens. At the MetroTrends blog, Urban Institute senior fellows Signe-Mary McKernan and Caroline Ratcliffe explain:

Whites in their 30s and 40s have about 3.5 times more wealth than African Americans and Hispanics in the same age group. By the time they reach their early-to-mid-60s, whites have seven times the wealth of African Americans and Hispanics. In other words, the average wealth gap has grown over time, and it also grows over the course of people’s lives.

Although the United States is one of the wealthiest countries, this prosperity remains out of reach for many Americans. Blacks and Hispanics, who strive to make a better life for themselves and their families, are not on the same wealth-building paths as whites. They are less likely to own homes and retirement accounts, so they miss out on these traditionally powerful wealth-building tools. Families of color also lost a greater share of their wealth in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Statistics from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances show that, between 2007 and 2010, black and Latino Americans lost significantly more than whites in overall wealth, home equity and retirement savings. Latino Americans were hit by far the hardest, losing nearly 45 percent of their wealth and 50 percent of their home equity.

In a Politico op-ed last month, NAACP CEO Benjamin Jealous cited some of these statistics to illustrate the lack of progress toward racial and economic equality since the 1960s, and America’s backward slide in the wake of the Great Recession. But “we can fix this,” he wrote:

There are steps we can take now to start to close the wealth gap. We need to hold banks accountable for predatory lending, and demand that corporations implement diverse hiring practices. We need to educate on these issues and reach out to local community groups to call attention to racial and economic injustice. And most importantly, we need to develop the will among our lawmakers and employers to take strong action to bridge racial economic inequality.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $24,000 by the end of today. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.