On June 19, the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca was the scene of a senseless massacre. The bloody battle took place in the rural town of Nochixtlan and resulted in the death of at least nine civilians. “Right now, the federal police are withdrawing, going back to their vehicles,” said a witness of the attack as he filmed the horrific scene. Bullets are heard smashing against metal traffic barriers on the roadside as the camera image shakes. Taking heavy breaths he calmly continued, “And as they retreat, they are shooting at us with firearms.”

A week earlier, police crackdowns had begun in various regions of Oaxaca state. These acts of violence are occurring in light of current protests in Oaxaca, where — since May 15 — the teachers’ movement has set up a peaceful plantón, or encampment, in the city center, and dozens of roadblocks across the state, including Nochixtlan. The teachers demanded a dialogue with the local and federal government about a recently approved education overhaul and the implementation of its neoliberal policies in Oaxaca.

The conflict first escalated when two of Oaxaca’s major union leaders were accused of money laundering, arbitrarily detained and taken to maximum security prisons on June 11. Tensions rose, the leaders were not released and police performed various intended evictions across the state, though none of these led to fatalities.

Initially the federal police force denied they were carrying guns, however, as evidence mounted, they were forced to admit that they were in possession of weapons. In addition to nine dead, the planned eviction on June 19 left over 100 people wounded and between 22 and 25 disappeared after a confrontation that lasted 15 hours — during which police used tear gas and automatic machine guns to repress the fierce protesters. Hospital workers on the scene were also attacked with tear gas.

Meanwhile Oaxaca’s Gov. Gabino Cue, who gave the order for police reinforcement in Nochixtlan, spent the evening at a wedding celebration.

Oaxaca didn’t take long to react.

Social networks were buzzing with activity and calls for solidarity. The morning after the fatal attacks, community radio and the church were informing people about the rebellion and calling them to participate in the barricades. The National Coordinator of Education Workers Union, or CNTE, a dissident movement within the government-affiliated national teachers union, released a statement demanding the resignation of Gov. Cue, while thousands took to the streets of Oaxaca city to raise their voices against police violence. “Fight, fight, fight, never stop fighting! For a laborers’, peasants’ and popular government!” the crowd shouted as they made their way towards the zocalo, or main square.

“We can’t negotiate about our deceased, there is no price they can pay for them,” said Victoria Tenopala Juárez, member of the Oaxacan Council of Autonomous Organizations and wife of political prisoner Cesar Leon Mendoza to the crowd in the square. “Unite! This fight is the people’s fight, and the reform affects us all.”

In 2014 Mexico’s ruling party — the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, led by President Enrique Peña Nieto — introduced a series of reforms to the health, energy, telecommunications and education sectors, among others. Ever since its proposal a year earlier, teachers slammed the education reform and its focus on labor policy, which they say is not actually concerned with the development of education and schools and is simply aimed at privatization. The recent local election of another PRI government in Oaxaca only confirms this tendency.

Protests to save public education and against the structural reforms have now taken place among many of Mexico’s labor unions, who demand an equal distribution of resources and an end to corruption in Mexico. “This is a very complex war. It did not start in Oaxaca. The teachers’ struggle, it is a global struggle. It started in Colombia, in Brazil, in Chile, in the United States — everywhere. And today we are in a war trying to say a very firm no to this kind of education,” Gustavo Esteva — an academic, La Jornada columnist and Oaxaca’s Earth University founder — told Democracy Now!“And we are saying no very firmly to all the so-called structural reforms that mean basically a change only of ownership.”

The teachers had demanded dialogue with the government ever since the introduction of the reforms, however, neither local nor federal governments conceded to any form of negotiation with the teachers until the morning of June 21 when the CNTE announced there would be a meeting with Interior Secretary Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong the next day. Aurelio Nuño, Secretary of Public Education, did not attend the meeting, and it was rescheduled to take place on June 27.

Already, the reform has had many debilitating effects for Oaxacan teachers. The most obvious are the precarious contracts and employment instability created by a standardized, nationwide evaluation, which will make it easier for teachers to be dismissed. Teachers in the states of Michoacán, Chiapas and Oaxaca have thus far largely resisted the execution of the evaluation. They defend their position by calling attention to how the reforms ignore the many cultural differences in a country as large and ethnically diverse as Mexico. “We aren’t against the evaluations,” said a teacher from the rural town of Tuxtepec. “We just want it to be a fair and contextualized one, that gives us a chance.”

Cultural Genocide and Resistance

With as many as 16 local indigenous languages, Oaxaca represents one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse states in Mexico. Furthermore, Oaxaca is rich in natural resources, with a long history of indigenous and campesino resistance, as well as one of the highest poverty rates in the country.

While corrupt government officials and transnational investment companies have denied people of their rights and appropriate their land under the pretence of “progress,” rural and indigenous communities often suffer consequences such as eviction, extortion, cultural annihilation and other forms of abuse and theft.

According to the CNTE, the recent reforms are nothing more than a continued attempt to promote homogeneity and an unceasing legacy of racist oppression in an already markedly unequal nation. Oaxaca, and in particular the teachers of Section 22 of the CNTE, have played an important role in resisting the reforms, garnering the support from dissident groups all over Mexico; day laborers of San Quintin, the Mexican Electricians Union, health workers, university students, parents of the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students and the Zapatistas National Liberation Army in Chiapas are only a few examples of the teachers’ national advocates. They support the movement against the privatization of education, as well as the right to access public services, labor rights, food sovereignty and an end to violence in the country.

In under a month, members of the CNTE in 18 states have joined the movement, endorsing its demands and setting in motion countless mobilizations across the nation. In addition to this, the movement is gaining support from indigenous communities across Oaxaca’s eight regions. The teachers have made it clear they will not surrender.

Teachers and souvenir sellers share the space below the canopies in the occupied main square of Oaxaca city. (WNV / Shirin Hess)

Teachers and souvenir sellers share the space below the canopies in the occupied main square of Oaxaca city. (WNV / Shirin Hess)

A majestic cathedral overlooks the encampment on Oaxaca’s main square; a sea of tents, sleeping bags and plastic canopies are raised above the sidewalks. “What they’re doing to us is subtle genocide,” said Euterio Garcia, an indigenous teacher in a community of Oaxaca’s northern mountain range. He argues the education reform represents a high risk for the continuity of Mexico’s indigenous cultures. “I am a bilingual teacher for Chinanteco and Spanish. I have no materials with which to teach my students, no books, nothing. There is no light or water in the village, and no proper plumbing. This is what motivates many of us. There are so many communities that are marginalized and forgotten. They don’t exist on the map, they don’t exist for the state.”

Garcia is among those fighting for a better future for the next generation of Mexico’s rural and indigenous communities. He is member of the CNTE’s local Section 22, which currently consists of between 75,000 and 83,000 members, time and time again proving its power before the Oaxacan state.

“We are like small cells, constantly multiplying and expanding,” said Garcia. “This movement is a grassroots movement, not one of leaders. Our leaders could be bought or coerced. But I, and others, aspire to continue the social struggle. That is why we are still here, after so many years of struggling.”

Garcia said that he, like many of his colleagues, is drained, and hopes that the government will yield before there is any more violence.

A Brief History of Mexican Teachers

The teachers’ struggle in Mexico has its roots in the beginning of the 20th century, forming what is now Latin America’s largest syndicate, the National Union of Education Workers, or SNTE. The SNTE is commonly labeled a corporatist union in alliance with the country’s 70-year ruling PRI party, while the CNTE has stood for horizontal and democratic union structures, bringing together many of the country’s regional teachers’ movements.

Worsening conditions for many teachers and schools in the poorest states of the country — in combination with the corrupt SNTE — played an important role in galvanizing national protests, and ultimately contributed to the formation of the CNTE in December 1979.

Oaxacan teachers of the union’s Section 22 developed important strategies for their movement and contributed to the longevity of the struggle over the years by carrying out peaceful encampments and roadblocks. During one of these encampments, in 2006, Gov. Ulises Ruiz Ortiz threatened to evict the teachers with the help of Mexican federal police.

The state ordered an attack on the teachers in the early hours of the morning, which galvanized massive popular support for the union. Community media played a crucial role in counteracting mainstream channels of information that demonized the teachers as corrupt troublemakers, and allowed their voices to be heard.

Days later, over 200,000 people streamed onto the streets of Oaxaca to denounce the local government and the dictatorial PRI party rule for their corruption and violent repression. For over five months, the teachers built barricades around the main square and Oaxaca became the scene of a massive popular uprising. Together with over 300 civil society organizations, the teachers formed the Popular Assembly of Oaxaca’s Communities, or APPO, which demanded and achieved the removal of the governor. Tragically, this success was achieved at a high cost. Hundreds of people were kidnapped, disappeared and tortured, and 26 were killed, including an American journalist.

A truth commission led by members of Oaxacan civil society organizations revealed that during the struggle, often referred to as the “Oaxaca Commune,” the state systematically violated human rights. According to author and academic investigator Jose Sotelo Marban, the repression exercised by the police and paramilitary towards the APPO activists falls under the clear definition of “state terrorism.” What happened in Nochixtlan on June 19, was a bitter reminder of these acts of state terror in 2006, almost exactly 10 years ago.

Consequences and State Repression

Violent repression and police vigilance are not uncommon in Oaxaca. “There are police roaming outside our school almost every day,” said Gabriela Reyes, a preschool teacher at a school in a low-income part of Oaxaca city (whose name has been changed for security purposes). “We’ve decided to get on with things and not to take notice of them.”

According to Reyes, the police are monitoring those teachers attending marches and making sure no classes are missed. Much of the stigma attached to the movement comes from media that label teachers as lazy and stress the time students lose while their teachers are out on the streets protesting.

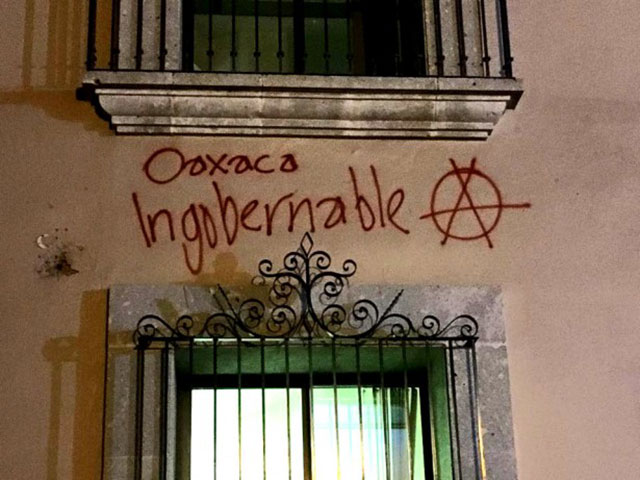

Graffiti appears all over the center of the city after the initial eviction at the State Institute for Oaxacan Education on June 14. (WNV / Chandni Navalka)

Graffiti appears all over the center of the city after the initial eviction at the State Institute for Oaxacan Education on June 14. (WNV / Chandni Navalka)

The teachers overcome this issue by working and covering the union duties in shifts, said Reyes. “It’s not easy, since we already lack staff,” she explained. “But we’ve made it work. In our case at least, 100 percent of the parents at our school stand behind us.” Victories such as free school uniforms and breakfast for students have proven to many parents that the teachers’ organization and persistence has born valuable fruits.

For Reyes and many other teachers in Oaxaca, the reform is predominantly a means of control that openly promotes homogeneity in society. “The reform allows no space for anything alternative in the curriculum. We pride ourselves on culture, heritage and a more environmentally-conscious education,” she said, also highlighting the danger of the reforms’ intention to replace teachers with professionals who do not possess any pedagogic skills or education. “How can we expect an engineer or a mathematician to know how to properly support a group of five-year-olds?”

While Reyes and many others claim the demands of the standardized evaluation are impossible to meet, the state has imposed another repressive mechanism by restricting teachers’ union participation. As if this weren’t enough, in the last five weeks over 4,000 teachers have been dismissed while the salary for others is being withheld as a direct consequence of their participation in the strikes and roadblocks.

Misleading Public Opinion

The teachers’ dissidence has not been beneficial to the Mexican state, challenging its power over the population. Scapegoating the teachers as the root of the problem in the media has been the easiest way for the government to take attention away from failures of the system, seriously underfunded public services and corporate greed and abuse.

As Mexican academic Maria de la Luz Arriaga Lemus states in her article about the democratization of education, the reforms “were passed with minimal input from the teaching profession.”

The educational reforms were created by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD; entrepreneurs, including Claudio X. Gonzalez, ex-counselor of the pro-government TV channel Televisa; and Mexicanos Primero, an education think tank founded by some of the richest and most politically influential men in Mexico. La Jornada’s Navarro has described Gonzalez as a “dubious” figure who likes to present himself as a social activist concerned about education in Mexico, while his “preferred activity in recent years has been to stigmatize teachers, discredit public education and intimidate those who do not bow to his will.”

In addition, the reform was backed by the “Pact for Mexico,” a participatory agreement between the PRI and two leading parties. All of this was decided almost entirely behind closed doors, without a debate, participation of students, parents or specialists, or the consideration of what educational policies have been implemented in the past.

In the midst of a frenzy of media attacks against the roadblocks, barricades and lost teaching hours, the fact that the Oaxacan teachers have come up with an alternative reform proposal has been pushed completely out of the spotlight. The proposal, which they have called the Plan for the Transformation of Education in Oaxaca, or PTEO, is based on four main principles: democracy, nationalism, humanism and communitarianism, and was written together with the State Institute for Oaxacan Education.

In addition to these principles, it emphasizes the importance of differentiating between Mexico’s cultures and aims to provide Oaxacan schools with more materials and basic infrastructure, such as classrooms, bathrooms and electricity.

Among Section 22’s current demands is the liberation of political prisoners, employment security, payment of all withheld salaries, and above all, a fair and peaceful dialogue with the government regarding these demands and the PTOE.

As tensions rise and Mexico’s teachers and their supporters prepare for the struggles that await them while they continue to protest peacefully, consciousness about what the reforms really mean for the country is starting to sink in for many people. The excessive use of force exercised by the government is absolutely inexcusable, and goes against the right to peaceful protest and the right to freedom of expression.

The barricades in Oaxaca’s city center remain, as do those in Nochixtlan and other rural areas. The people of Oaxaca understand the importance of an autonomous and free education. They know that it is not only education that’s subject to privatization, but that Mexico’s resources on indigenous and communal land are also at great risk of being stolen or appropriated. “They are selling our land, our territory,” said Esteva. But he knows Oaxaca too well. “The people are resisting.”