About 15 years ago, Darrita Davis was selling clothes out of her trunk in Dayton, Ohio. She had just gotten back from New York City, where she bought her inventory wholesale. She had designer belts and glasses, velour jogging suits, and pants and shirts covered with the logos of NBA teams, which were popular back then.

Davis usually followed a rule to not sell at night, but she ran into a friend who pleaded with her, knowing she would sell out of the good stuff before he saw her next. After the sale, as she packed up, she saw someone approach out of the corner of her eye. She didn’t think twice about it because she recognized him from her son’s football league.

“He walked straight up to me and said, ‘You have some fly ass shit,'” Davis said. “And he pulled out the gun. I didn’t see it, I just felt it in my back. I kind of immediately turned and looked at him and slammed the trunk down, and was like, ‘You would have to kill me tonight. This is how I’m supporting myself.'”

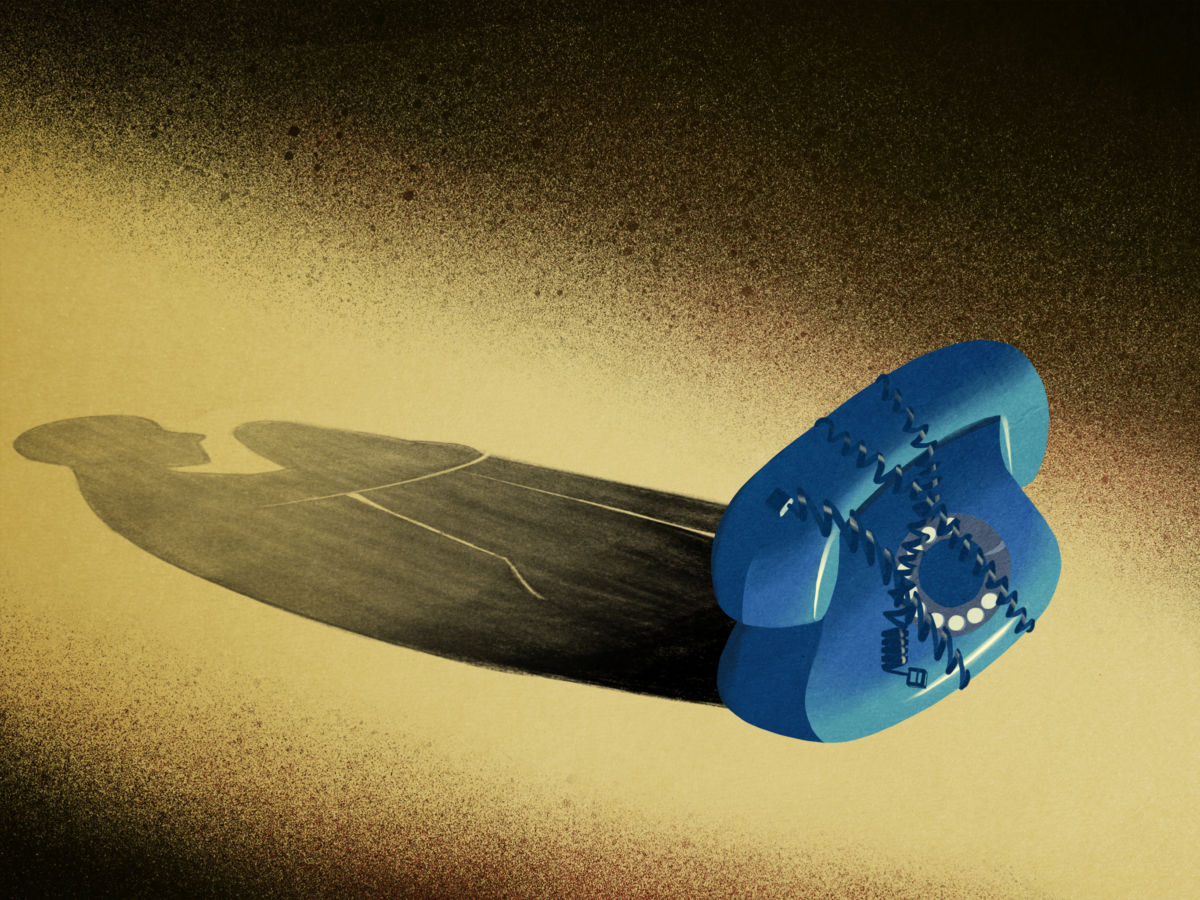

The man backed off, claiming he was just messing with her. Davis didn’t believe him. She was also shaking with fear. But she didn’t call the police. It never occurred to her.

“Nothing good comes out of calling the police,” she said. “Never, ever.”

Every year, millions of violent crimes go unreported. Some victims don’t call the cops because they think what they experienced was a minor incident, and they barely feel like victims. A relative handful would call, but don’t because they’re afraid of reprisal. But the majority choose to not call. Altogether, more than half of the assaults, rapes and robberies in the U.S. aren’t reported to law enforcement, according to the 2017 National Crime Victimization Survey.

Forty percent of sexual assaults prompted a call to the police, along with 45 percent of assaults and 49 percent of robberies, the survey found. Overall, victims reported 45 percent of violent crimes.

The staggering numbers are an indication that the criminal legal system — its methods, its outcomes, or both — alienates victims on an enormous scale. And that has consequences, because victims are its most important gatekeepers. The rate at which they decide to not call the cops raises fundamental questions about the system’s effectiveness, especially in light of recent research indicating that most victims are skeptical of punitive, carceral justice.

Sixty-one percent of violent crime victims are in favor of shortening prison sentences to invest more in prevention and rehabilitation, according to the 2016 study, “Crime Survivors Speak.” Fifty-two percent say imprisoning people makes them more likely to commit more crime — just 19 percent say prison is rehabilitative.

Looking back, Davis said her decision to not call police was based on several factors. She didn’t think the police could help her, and didn’t want to waste her time. She didn’t have a vending license, and didn’t want to be questioned about that. She knew the criminal legal system breaks up families. She also cited the credo that “snitches get stitches.”

“It’s just the level of respect,” Davis explained. “We take care of our own community. We handle our own — anytime we involve outside sources, something negative happens.”

Back in 1982, President Ronald Reagan’s Task Force on Victims of Crime released a searing and seminal report, finding that the criminal legal system was biased in favor of “criminals” and against “innocent victims.” Defendants get a free lawyer, food and housing, the report argued, so victims should get help, too, in the form of restitution, government assistance and stronger protections against intimidation. It also recommended jailing more defendants, getting rid of parole and lengthening prison sentences.

The report proudly noted that it included no data to support its conclusions. Instead, it featured the narrative of a “composite of a victim of crime”: a 50-year-old woman is raped and robbed in her home by a stranger, and struggles to put him behind bars.

“You cannot appreciate the victim problem if you approach it solely with your intellect,” the authors wrote.

Narratives like the one in the 1982 report powered the rise of the punitive Victims’ Rights Movement, which is centered on improving victims’ standing with police, prosecutors and judges. But data indicate that Davis’s story is more representative of the experiences of victims of violent crime.

Like Davis, victims tend to be young, to be people of color and to be hurt by someone they know. The vast majority of violent crime victims also say imprisoning someone makes them more likely to commit further crimes, a recent study found. The Reaganite binary of “innocent victims” and “criminals” is inaccurate, too — crime victims are much more likely than the average person to have broken the law, and people who break the law are much more likely to have been victimized.

But it’s hard to overstate the depth and breadth of unreported crime — how normal it is for Americans from every background to conclude that the criminal legal system would not serve their interests. Victims of violence don’t call the cops at high rates in seemingly every cross section of society — including white people, old people and people with money.

Victims’ reasons for not calling are complicated, and they remain poorly understood because the research is hard to come by. By definition, there are no official records of these incidents, and the detail of the data is limited by people’s impatience with surveys.

“We have to ask: Why is it that so much of it still remains unreported? Is it just an assortment of personal idiosyncrasies?” said Janet Lauritsen, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “It’s kind of a puzzle and I don’t think anybody’s working on that.”

The top reason victims give for not calling the cops is that the crime was a “private or personal matter handled informally,” and Davis’s thinking seems to fit into that category. After the man who stuck her up backed off, she walked over to the friend she sold to that night and told him what happened. He and a couple others confronted the man, who told them his story — that it wasn’t a real robbery. The incident ended there. Another friend got her a pistol, but she didn’t like the “wild, wild West” feeling it gave her, and so she didn’t carry it.

“I chilled for a while,” Davis said, summing up how she recovered emotionally.

Thirteen states deny victim assistance to some people with felonies; 43 of them won’t help victims who were involved in the crime that led to their injury; and all 50 only help victims of reported crimes, a 2014 report found. Those rules harden the cycle of victimization and criminality, advocates say.

Services, as a result, remain largely inaccessible for many victims, explained Davis, who’s now the lead organizer of the Akron Organizing Collaborative, which works to transform the criminal legal system through its People’s Justice Project. She said the local victim assistance office has turned people away, and told them to contact her instead.

Davis wants new systems to keep her city secure — ones that don’t have people with badges and guns at the center. She imagines a future where calling for help doesn’t have to mean calling 911. But alternatives, across the US, remain few and far between.

“It’s almost like creating a new structure of — I don’t want to say law enforcement,” Davis said. “Just of community safety.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.