A series of explosions were heard on April 28 up to six kilometers away from the Civic Center, the square in which the legislative assembly, state justice, and state government Paraná and the city of Curitiba (Paraná’s capital), in the southern region of Brazil have its main offices. The clashes were the result of violent acts by the military police against public servants, mostly teachers of the state of Parana.

On April 28, they protested against a series of tightening measures that the Legislature began to put up for vote for a second and final time. By late afternoon, it was known that there were at least 107 wounded – two policemen and 105 protesters. These ghastly numbers indicate a real massacre.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Tasques.)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Tasques.)

Reports during the night accounted for over 150 injured. Eight of the protesters are in critical condition due to injuries from police dog bites and rubber bullets.

On Monday, skirmishes between military police and public servants were registered, but on a smaller scale than the fateful and already historic April 29. On Monday, the MEPs had approved in the first vote, by 31 votes in favor against 21 such pacotaço, pushed forward by the governor Beto Richa (PSDB) to improve state’s finances, whose balance sheets Richa indicated would be in blue skies in his election campaign for re-election last year.

For over an hour and a half, gas bombs and stun grenades outside the state parliament showed that they were the true guarantee for the final vote inside the building, enforcing the will of Richa and his government team, led by Mauro Ricardo Costa from a Bahia, who was imported to Parana by PSDB for his second term and known for its services in the treasury area of the Municipality of Salvador (BA), ACM Neto management (DEM), and the government of São Paulo, in the management of José Serra (PSDB). The session continued without an end in sight, until the completion of this report.

However, as bombs, dogs, rubber bullets and batons fell on protesters armed only with their calls and slogans, politicians concerned about the violence that unfolded in the main square, opposite the Our Lady of La Salette Assembly (tragic ironic name), came out of the building to request that the police calm down. The green-party politician Rasca Rodrigues stood side by side with the wounded civil servants during the confusion and widespread barbarism in the square. He was bitten by one of the dogs of the military police’s SWAT team, in addition to being sprayed with pepper spray and tear gas. He returned to the building with blood running down his arm.

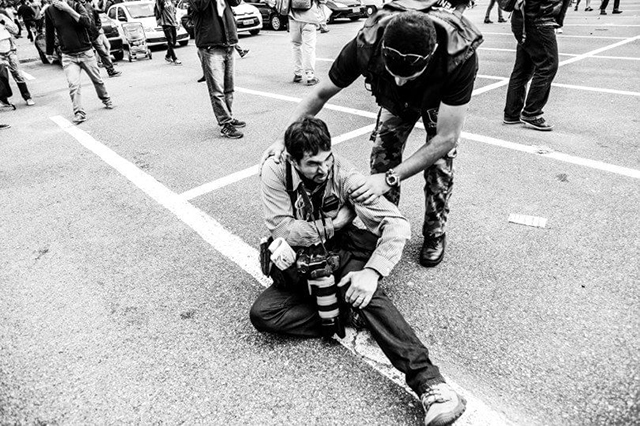

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques.)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques.)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Prohibited from approaching the Legislative Assembly by a human chain 1,500 police officers, most officers from rural battalions and with no guarantee of their daily wage, the protesters were forced make their way back in the face of the intense police crackdown. They came back running toward the avenue Cândido de Abreu, the main connection route to the Civic Center. They were not alone.

“Many people came carrying others, by their legs and arms, as if wounded from a war camp, unconscious and injured.”

The nearest building where they could wait for help was the City Hall, currently headed by Gustavo Fruet (PDT), an opponent of Richa, who prevented his candidacy as mayor in 2012 by the PSDB, who ran a political campaign and won as the underdog.

The lobby and nearby rooms where property taxes and local taxes are charged, were transformed into a field hospital. Videos from smartphones of the wounded, bleeding and shirtless protesters began to be circulate on the internet. Work tables turned into stretchers, and the hospital few stretchers that actually arrived on scene, struggled to get close to the Civic Center due to the police blockade of nearby streets, and the fleeing crowd on the main avenue and sidewalks.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

The prefecture services throughout the City was interrupted so that the injured could be carried out. There, 35 bodies were attended to, many of them with bruises, from head to toe from the rubber bullets and rifles of riot police. Others had difficulty breathing from inhaling the dispersed gas, in addition to those hit by clubs. Witnesses among the protesters have reported seeing a helicopter with police firing bomb flybys, in what would be the first air attack in the country against its own civilians.

A municipal nursery in the Civic Center located a few blocks from the square where the war continued witnessed within its walls all the terror caused by police. If six kilometers away, the noise of the bombs was still surprising, as discussed earlier in this report, one have an idea of the intensity of the clashes and echoes heard at the child day care. Explosions and the screams could be heard, in addition to loud car sounds and nauseating smoke dispersed from the gases. The kids, staff, and teachers cried in fear, having no one to turn to, hoping it would end as fast as possible, which did not happen.

From the military point of view, the police fulfilled, even with the use of excessive force, the mission of keeping the protesters away from the Assembly, which it had failed to do in February when Richa tried to put the pacotaço into voting for the first time. The vote was rejected by the presence of 20,000 protesters and a one month strike by teachers, the largest category of civil servants, with 50,000 professionals. At that time, the deputies of the ruling bench had to enter the Assembly within its obsolete and giant police paddy wagon black. They tried to direct the voting of the meeting to a restaurant, since the floor had been occupied, but were afraid of the possible reaction of the demonstrators and decided to delay the attempt.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

As can be seen, it was a matter of time for Richa to assimilate the retreat, reorganize the army, both the faithful Assembly, as well as the bullets, bombs and clubs, to assert his project that violates several servants’ rights, such as logging permits of the teachers, the free use of resources from state funds, including the judiciary, increased VAT rate from more than 90,000 products, and changes in the security of the servers sector, which will oblige them to pay an extra index case order to keep their full salaries over $ 4600 reais (approximately 1.600 US Dollars).

“The political price to be paid for the main actors of the episode, as Richa and their collaborators in government and Assembly, is still so nebulous and malleable as the white smoke of the bombs that engulfed the Civic Center and was amply captured by cellphones in nearby buildings.”

Before the reader is surprised at the direction in this part of the text, here is a little recent history of local politics. On August 30, 1988, the PM repressed in the same Civic Center, a protest by teachers of the state, then the government of Alvaro Dias, then the PMDB, and today Senator affiliated with the PSDB. Many decreed the end of his political career, marked by the cavalry trampling unarmed teachers, but Alvaro continues to be strong in the lead. Taking away two circumstantial defeats the Paraná government, against Jaime Lerner in 1994, the political novelty that year, and Roberto Requiao, in 2002, supported by no less than President Lula, the slack of time, Dias is Senator with the most mandates elected. He won, for example, another eight years in 2014. He had been elected in 2006 and in 1998, all of them after the beatings of 1988.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Richa has a more uncertain fate, but no less favorable. Richa embodies the visceral anti-leftism of much of the current Paraná electorate. Over time, as a political whole, it can be benefited by the natural dilution of Dantesque episode, as well as with Alvaro Dias. The difference is that, for the massacre of size and constant presence on the Internet (tool nonexistent at the time of Álvaro), Richa can spend what’s left of his second term trying to explain the “hows” and “whys” of such violence against professional educators. What’s more, much of Paraná’s population, as well as Brazil, still marks their daily routine in front of the television for news of FTA broadcasters. Tonight, Richa can be benefited or not by the editorial filters and supposedly journalistic criteria (“not to abuse images, there are many children watching right now,” can be one of them, yes) thrown by hand by publishers and heads of broadcasting.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

The Richa administration also faces deep investigation into alleged payments of bribes to officials from the state revenue of Londrina, in the north of Paraná, his hometown, for companies under pressure to get rid of any inspection and collection of fiscal agents. One of the most awarded journalists from Brazil, while investigating the case, had to leave town because he received information that would be killed in fake robbery at a steakhouse that he attended. Richa’s cousin, Luiz Abi, is suspected of being behind the bidding fraud for government car repairs an issue that threatened the journalist, James Alberti, from the Rede Globo affiliate in Paraná had also investigated in Londrina. Abi was arrested at the request of the prosecution, but now is waiting for his trial out of custody.

Beto Richa is the son of José Richa (died 2003). Richa’s father played an important role in the era of democratization, when Tancredo Neves was elected president in the Electoral College January 1985. If the military hardliners decided to prevent the possession or not to recognize the results of the indirect election made in Congress , Richa’s father had committed to participate in a plan to house Tancredo in Paraná and resist a possible coup attempt, putting its military police, to protect the new civilian president. Today, thirty years later, the same corporation, under the plan of another Richa, makes the opposite way, the rampant violence, without any connection with the democratic guarantees as advocated by his own father, as was made explicit in the afternoon of April 29, marked by cold and drizzle that fell in the center of power of Paraná’s Capital.

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Curitiba, Paraná, April 29th, 2015. (Photo: Leandro Taques)

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.