Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Despite the fragmentation of Mexico’s left movements, thousands demonstrated – against education and labor “reforms,” attacks on indigenous rights by multinational mining companies, and privatization of the oil and electricity industries – on the 20th anniversary of the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

On January 31, 2014, on the 20th anniversary of the North American Free Trade Agreement, two huge marches in Mexico City opposed the corporate reforms of Mexico’s economy and politics. Marchers especially protested the most recent reforms – the privatization of the oil and electrical industry, the introduction of US-style standardized testing, attacks on teachers, and changes in labor law that will weaken unions and give employers the right to hire temporary and contingent workers.

Teachers in the National Coordinadora of Education Workers (CNTE) and members of the Mexican Electrical Workers (SME) marched in the morning. The unions of the National Union of Workers (UNT) and their allies marched in the afternoon. The morning march included about 2,000 participants, including hundreds of teachers from Oaxaca who have been camping out since the beginning of the school year in a planton in the Plaza de la Republica. The afternoon march included tens of thousands of people.

The division reflected the participation in the afternoon march of large contingents of the Party of the Democratic Revolution, the most left of Mexico’s three major parties. The UNT invited Cuauhtemoc Cardenas to be the march and rally’s sole speaker. Cardenas is the son of Lazaro Cardenas, Mexican president in the 1930s who expropriated the property of US oil companies and nationalized the industry. Cuauhtemoc Cardenas ran for president twice and was denied victory by massive fraud in 1988. He then helped organize the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), which he formally leads.

Cardenas invited the participation of the PRD in the march. Teachers and the SME then withdrew to organize their own march, because the PRD deputies in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies had supported the education reform and failed to oppose strongly the energy reform. In addition, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, former Mexico City mayor and the PRD’s presidential candidate in the past two elections, registered a new party, MORENA, the day before the march. Lopez Obrador announced that it would not run joint election campaigns with the PRD and did not participate in the afternoon march.

While the internal problems of the progressive movements in Mexico are an obstacle to the growth of an effective movement to oppose corporate globalization, many advances have been made in the past 20 years in which NAFTA has been in effect. The left governs Mexico City and several states, although the PRD has deep internal divisions and many people are leaving to join MORENA.

When NAFTA went into effect in 1994, solidarity between Mexican, US and Canadian unions and popular movements hardly existed. Today, solidarity networks share a common political perspective and are capable, at their best, of organizing mass actions that express the rejection of the free-trade model by a majority of people in each country. The two marches in Mexico City coincided with simultaneous marches and demonstrations in many cities throughout the United States and Canada.

Binational organizations exist today as well, coordinating opposition. The Indigenous Front of Binational Organizations (FIOB) organized marches and rallies a few days later in Oaxaca, Baja California and California. “We oppose the structural reforms of energy, education, finance and politics, because they respond to the needs of transnational corporations and harm indigenous and marginalized people,” said FIOB binational coordinator Bernardo Ramirez. “We reject as well the mining concessions and the privatization of public services and industries, such as water, education and electricity. They are robbing Mexicans of their national wealth and condemning a majority to poverty, and with it, forced migration.”

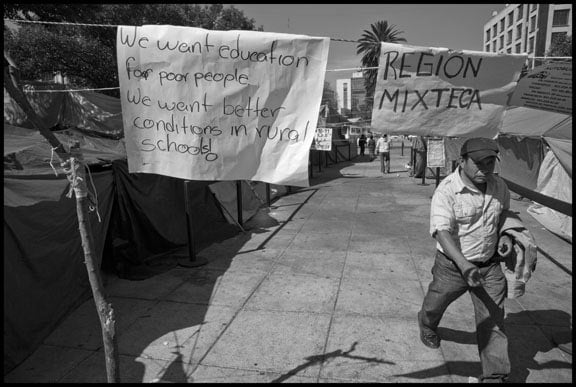

A striking teacher walks through the teachers’ encampment, or planton, in the Plaza de la Republica. Left-wing teachers, members of the National Coordinadora of Education Workers, have been living here in protest of education changes that would impose standardized testing, like that in the United States. The region Mixteca is part of the state of Oaxaca, which has the largest union of radical teachers in the country.

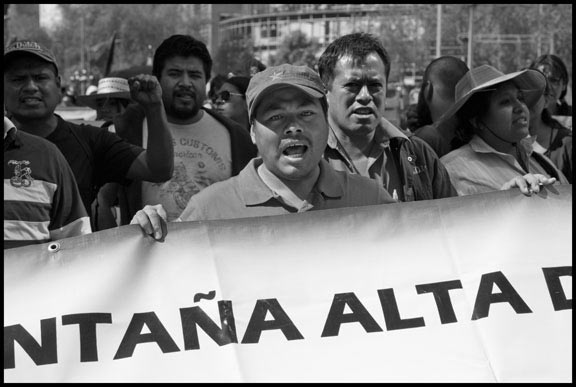

A striking teacher from the state of Guerrero wears a red star on his cap as he walks behind the banner in the teachers’ march against education reform on the 20th anniversary of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

A teacher from Guerrero holds a banner with the face of Lucio Cabañas, who led a guerrilla struggle against the Mexican government in the 1960s and 1970s. Cabañas was a teacher and a founder of the Party of the Poor. Radical teachers in Guerrero and other states look up to him as a hero because he organized poor farmers in the countryside to fight against the oppression of the government and landlords.

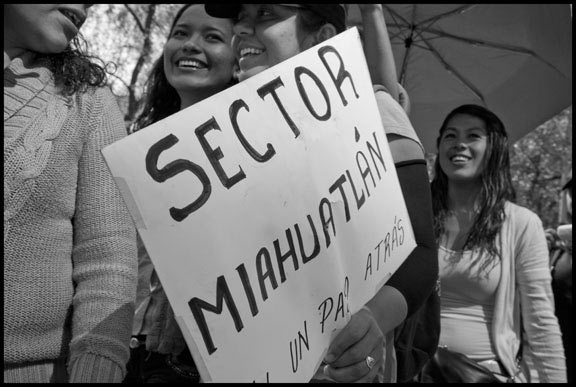

Teachers from Miahuatlan, a municipio in Oaxaca, carry a sign that identifies the region they’re from and says “Not One Step Backward.” Are they happy because it’s a pleasant day for the march or because they believe in what they’re marching for?

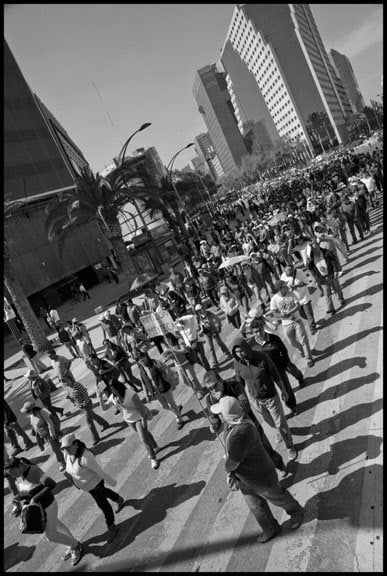

The march of teachers and fired electrical workers turns from the Reforma onto the street leading down to the Zocalo. In the most luxurious hotels in Mexico City, government officials and corporate executives meet and make the decisions and polices that the marchers are protesting. To the wealthy, these marchers are upsetting the natural order of the world they control.

Young teachers from Oaxaca hold a banner announcing their support for their counter-reform program, PTEO, which their union has designed as an alternative to the government education reform that their march is protesting. They call the government plan “poison” because it threatens to take social consciousness and the love of teaching out of the schools.

As teachers march around him, a young boy pushes a cart loaded with goods for a sidewalk stall. Thousands of boys like him stop going to school and start work very young to support their families. Behind the marchers rises the luxurious Hotel Melia, which towers over the dome of the monument to the Revolution that promised to favor the poor over the rich.

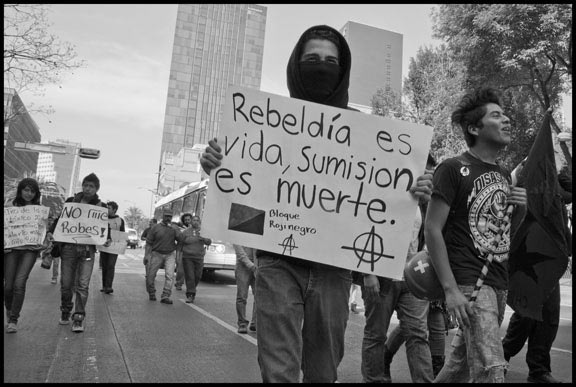

A masked young man carries a handmade sign saying, “Rebellion is life, Submission is death.” He and members of the Red and Black band of anarchists march in support of the teachers and electrical workers. Others of this group carry signs accusing the subway system of robbing workers and the poor. Mexico’s history of anarchist movements stretches more than a century.

The broken-down van of the Mexican Electrical Workers Union (SME) drives in front of the banner held by fired union members. In the window is a sign supporting the presidential campaign of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who was a progressive mayor of Mexico City. Forty-four thousand workers were fired when the federal government dissolved the state-owned power company for the city as a prelude to passing a constitutional amendment allowing it to be privatized.

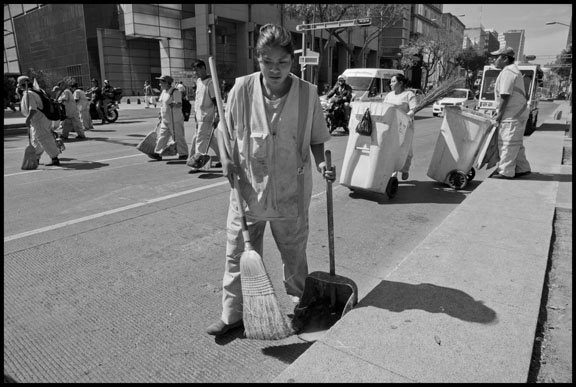

Behind the march of the teachers and electrical workers come the city workers with brooms and trash cans to sweep the streets and remove all traces that the marchers had passed by only minutes before.

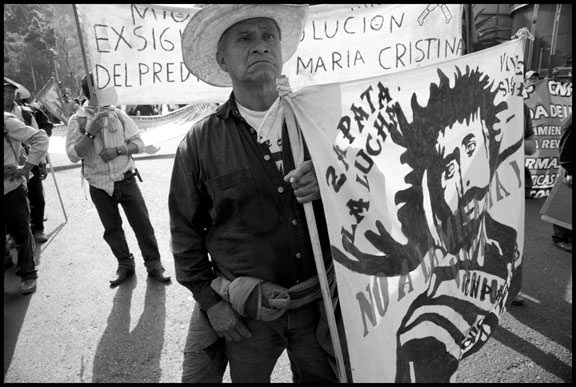

A campesino carries a banner in the march against reforms and NAFTA organized by the National Union of Workers. The banner celebrates Mexican revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata and opposes the expansion of huge corporate mining, which has caused conflict in rural communities and displaced thousands of farmers.

One woman carries her toddler on her back as she walks in front of her grandmother. People from the countryside, including many women with children and older family members, went to Mexico City to march against the economic reforms.

Two women from the community organization COPAZ were part of a contingent of hundreds of people mobilized for the march against the reforms by the local branch of the Party of the Democratic Revolution. Azcapotzalco is the most industrialized borough of Mexico City and a stronghold for the left in the city’s politics.

A group of activists from Puebla, members of the Independent Urban and Popular Movement of Workers and Campesinos. The organization is part of the Coordinadora Nacional Plan de Ayala – National Movement for Human Rights. Most of its members are indigenous people who oppose the militarization of Mexican society under the pretext of the “war on drugs” and the violations of human rights. They also oppose the corporate mining and hydroelectric megaprojects that displace rural communities.

Workers and farmers from the CNPA-MN hold sticks with their banner at the edge of their contingent of marchers, to keep everyone walking together. Their hands are those of people who work hard for a living.

Activists from a left-wing Mexico City neighborhood political organization, the Francisco Villa Popular Front, wait to join the march. They stand in front of the glass dome and skyscraper that house the Mexico City stock exchange, whose members reap the rewards from the economic reforms that the march opposes, such as the privatization of oil and electricity and NAFTA.

Telephone workers hold the banner of the Union of Telephone Workers of the Mexican Republic. The old banner shows the age of their local union, because it carries the symbol of the dial of an old telephone, which young people today would not even recognize. The union is one of Mexico’s oldest and is a founder of the independent and democratic union federation, the National Union of Workers.

Benedicto Martinez raises his fist in a contingent of marchers who have come from Canada and the United States to support Mexican unions and to oppose NAFTA on its 20th anniversary. Martinez is the general secretary of the Authentic Labor Front, one of the most progressive and independent unions in Mexico. More than 20 years ago, he toured the United States as part of the “Free Trade Express” to tell US workers that unions like his opposed the negotiation of NAFTA.

Leaders of the union for workers and professors at Mexico’s National Autonomous University link arms in the march against economic and education reforms.

Two women, rank-and-file activists in the Party of the Democratic Revolution, step into the march behind a banner that opposes the energy reform, which would privatize Mexico’s oil industry. A man in a cowboy hat follows them, while behind them are young people in a drum corps.

Copyright: David Bacon

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $38,000 in the next 6 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.