Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Hundreds of Maya Q’eqchi’ residents of El Estor attended the burial of Carlos Maaz Coc, a 27-year-old Maya Q’eqchi’ fisherman fatally shot by police May 27 during a crackdown on a protest against mining in eastern Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Hundreds of Maya Q’eqchi’ residents of El Estor attended the burial of Carlos Maaz Coc, a 27-year-old Maya Q’eqchi’ fisherman fatally shot by police May 27 during a crackdown on a protest against mining in eastern Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The clouds of tear gas began to dissipate, and the crisp sounds of gunshots punctuating the chaos halted. Someone was lying in the middle of the road.

Riot police had wasted little time before firing tear gas toward the blockade that the local association of small-scale fishers had set up May 27 on the road leading to the Fenix nickel mine. The group blames the mining operation for polluting the lake on which they rely. Everyone scattered as the police Special Forces advanced. Most people retreated to a three-way intersection along the edge of El Estor, or further into the town, in eastern Guatemala; others re-grouped on the other side of the blockade site, towards the mine. Police removed the rocks, branches, and barbed wire laid across the road, and continued firing tear gas now and then in several directions.

Riot police fire tear gas as they advance to evict a road blockade set up by fishers protesting mining pollution in El Estor, Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Riot police fire tear gas as they advance to evict a road blockade set up by fishers protesting mining pollution in El Estor, Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

But then the riot police began firing bullets. It wasn’t long before someone was lying in the middle of the road.

When the gunshots subsided, those of us who were closest began running toward the figure in the road. Someone else had already been helped out of the way, with what appeared to be a bullet wound to the lower back. We only made it a few meters before police opened fire again.

We didn’t have time to see if they were shooting at us or sending warning shots into the air. Everyone bolted to the side of the road and hit the ground or took shelter by the walls of buildings on the lower side of the intersection.

The police were in the process of retreating right past the same intersection, taking the upper paved boulevard. When the gunshots again subsided, people once again began heading towards the man lying motionless in the middle of the road. Some of us faced the retreating riot police holding our hands in the air while others yelled at them, “Don’t shoot!”

Carlos Maaz Coc was dead, lying on his back with lifeless eyes staring up at the sky. He was 27 years old. On the left side of his chest, the young Maya Q’eqchi’ fisherman’s shirt was soaked with blood. His younger brother was already kneeling at his side, his cries of anguish ringing out as people began to gather around the body.

Carlos Maaz Coc was shot and killed by police on May 27 in El Estor, Guatemala. This photograph has been published only because his death was denied by some official government statements. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Carlos Maaz Coc was shot and killed by police on May 27 in El Estor, Guatemala. This photograph has been published only because his death was denied by some official government statements. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The following day, on May 28, hundreds of Maya Q’eqchi’ accompanied the funeral procession from the home Maaz Coc shared with his 22-year-old wife and their eight-year-old son in El Estor to the local cemetery. That same day, the Guatemalan Ministry of the Interior issued a statement, providing an official update on the situation and a key clarification: no one had died.

“What the company does is send police to kill people,” Jorge Xol said in an interview after the burial of his son-in-law, whose death the government denied. “If we just leave things like this, any police officer can kill someone else.”

Since the killing of Maaz Coc, leaders of the Guild of Small-scale Fishers (Gremial de Pescadores Artesanales de El Estor, GPA) that organized the protest action have been facing intimidation and criminalization. In spite of the backlash, they took to the streets of El Estor once again on July 7, leading a march to reiterate their demands concerning mining activities and lake pollution and to demand justice for the killing of Maaz Coc.

“The struggle will continue. This isn’t just going to be forgotten,” said GPA president Cristóbal Pop.

The Guild of Small-scale Fishers of El Estor engaged in a series of protest actions in May, putting a halt to mining-related traffic to and from the Solway Group’s Fenix nickel mine in eastern Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

The Guild of Small-scale Fishers of El Estor engaged in a series of protest actions in May, putting a halt to mining-related traffic to and from the Solway Group’s Fenix nickel mine in eastern Guatemala. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Years of Mining, Decades of Repression

Maaz Coc is far from the first killing connected to the mine, located along the northwestern tip of Lake Izabal, six kilometers east of El Estor. The history of the Fenix nickel mine is a decades-long story of conflicts, disappearances, killings, and impunity. Mining interests first made headway in the area in the 1950s and 60s, during the military governments that followed the US-backed 1954 overthrow of Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz, who enacted sweeping agrarian reform and granted political rights and freedoms.

The year 1960 also marked the beginning of a 36-year armed conflict between left-wing guerrilla forces and the US-backed Guatemalan military and paramilitary forces. A UN-backed truth commission later concluded that the Guatemalan state was responsible for more than 90 percent of violence, including an estimated 200,000 civilian deaths, and that it carried out acts of genocide against Maya Peoples in four regions of the country.

At the time, the Guatemalan state had a stake in the EXMIBAL nickel mining company, a subsidiary of the Canadian International Nickel Company (INCO). Two members of a high-profile ad-hoc commission formed in Guatemala City to investigate the issue of mining rights in the area were killed in 1970 and 1971, under the administration of General Carlos Arana Osorio, and another commission member was forced into exile. Following the killings, EXMIBAL and INCO were given the green light by Arana Osorio.

The nickel mine only operated for a few years beginning in the late 1970s, but the companies never relinquished mining rights or the contested lands they claimed to own. Leaders of Maya Q’eqchi’ communities struggling for land rights and titles in the area were disappeared and killed in the early 1980s. The UN-backed truth commission later documented the active participation of mining company personnel alongside government and paramilitary forces in violence and repression in the area.

Now owned and operated by the Solway Group, the Fenix nickel mine and installations have been tied to violence and repression for decades. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Now owned and operated by the Solway Group, the Fenix nickel mine and installations have been tied to violence and repression for decades. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

In the 2000s, mining interests picked back up in the area. Skye Resources, a Vancouver-based mining company, bought the project from INCO in 2004. Both Skye and the Fenix project were acquired in 2008 by Toronto-based Hudbay Minerals, which then sold its interests in 2011 to the Solway Group, a Russian conglomerate with headquarters in Switzerland. Solway is the current owner of the Fenix mine, nickel processing plant, and the Guatemalan subsidiaries CGN and PRONICO.

Violence and repression surged alongside the renewed interest in reopening the Fenix mine. State and company security forces carried out a series of violent evictions of Maya Q’eqchi’ communities and land occupations in the mid-to-late 2000s, in contested lands claimed by the mining companies. Eleven Maya Q’eqchi’ from the Lote 8 community are moving forward with a civil lawsuit against Hudbay Minerals in Canada for the participation of mining company personnel in gang-raping them during a 2007 eviction.

Two other Canadian lawsuits are being brought against Hudbay by other Maya Q’eqchi’ plaintiffs: Angélica Choc, the widow of Adolfo Ich; and German Chub. In 2009, Ich was brutally murdered, Chub was shot and paralyzed, and other local Maya Q’eqchi’ were injured in a crackdown on protests against the mining company over land rights. Mynor Padilla, a former military coronel and head of mine security at the time, stood trial in Guatemala for homicide, aggravated assault, and other charges, but was acquitted earlier this year. Appeals are currently underway.

German Chub was shot and paralyzed in 2009. The acquittal of former head of mine security Mynor Padilla by a Guatemalan court was appealed, and a civil lawsuit is moving forward in Canada. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

German Chub was shot and paralyzed in 2009. The acquittal of former head of mine security Mynor Padilla by a Guatemalan court was appealed, and a civil lawsuit is moving forward in Canada. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Community leaders and others fighting for land rights and justice in the region have faced threats, intimidation, and attacks. Over the course of Padilla’s trial, Choc and other witnesses faced threats and intimidation, including a nighttime attack that involved gunshots at Choc’s home while she and two children were sleeping inside. In 2012, a group of armed men shot two of Lote 9 community leader Rodrigo Tot’s sons while they traveled by bus from El Estor to Guatemala City. One son survived, but Edin Leonel Tot Sub, a 29-year-old father of three, did not.

The Fenix mine and nickel processing plant began operating again in 2014.

Small-Scale Fishing Families Organize, Garner Regional Support

In El Estor and in communities around Lake Izabal, the largest lake in the country, many families rely on small-scale fishing activities for subsistence. Lake pollution from African palm, banana, sugar cane, and other agribusiness monoculture plantations has been a concern for years, as has acid mine drainage and other potential mining-related contamination, particularly now that the Fenix mine is once again active.

Earlier this year, four local fishers’ associations in the municipality of El Estor came together to form the GPA, whose members are overwhelmingly Maya Q’eqchi’. Frustrated with a lack of reliable information about the pollution of Lake Izabal and mining activities, the guild took action in May. For 12 days straight, they maintained a protest between El Estor and the mine, allowing free passage for all other vehicles but prohibiting that of any trucks or vehicles carrying ore, mining equipment, personnel, or materials to or from the mine. Among other demands, they called on the government to conduct studies into lake pollution, provide access to mining licenses and other documentation, and shut down the mine.

“Due to the pollution, as small-scale fishers and as El Estor residents, we demand that the Ministry of Energy and Mines and the Ministry of the Environment cancel the exploitation license of the CGN mining company in the municipality of El Estor, Izabal,” the GPA wrote in a statement during their 12-day protest action in early May.

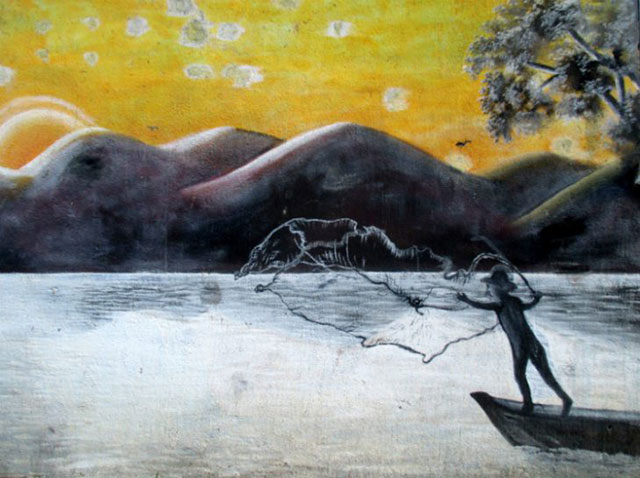

Maya Q’eqchi’ families and others in communities around Lake Izabal rely on small-scale fishing activities for subsistence. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Maya Q’eqchi’ families and others in communities around Lake Izabal rely on small-scale fishing activities for subsistence. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

News of the mobilization efforts of fishers in El Estor inspired others in the region. In Castillo San Felipe de Lara, located where Lake Izabal meets the Dulce River, some 300 local fishers formed their own association.

“As soon as we heard they were protesting, we quickly organized ourselves and supported them,” said Junior René Bac, one of the leaders of the new group. “The creation of the committee is so that they [the government] listen to us, that Lake Izabal is being affected by the CGN company, and is being affected by these land-based companies – sugar cane, banana, African palm, and others.”

The GPA’s actions and demands resonated with the Castillo San Felipe de Lara fishers. “We speak but aren’t heard,” said Bac. “If the [mining] company can be stopped, let it stop. It’s a very sensitive issue. Without the lake, we here [in the Izabal department] are nothing.”

The GPA’s actions and demands were also supported by other sectors in the region, and particularly in the town of Río Dulce, an important hub located where the road from El Estor meets the main road leading up into the Petén department and down to the Atlantic highway that runs between Guatemala City and Puerto Barrios, a Caribbean town and industrial port. As a key jumping off point for Lake Izabal boat rides and trips downriver to Livingston, as well as a refuge for yachts seeking shelter during the hurricane season, Río Dulce’s economy is primarily based on tourism.

Spanning the Dulce River that flows from Lake Izabal to the Caribbean, the town of Río Dulce’s economy is based on tourism and has been negatively impacted by mining activities in the region. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Spanning the Dulce River that flows from Lake Izabal to the Caribbean, the town of Río Dulce’s economy is based on tourism and has been negatively impacted by mining activities in the region. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

“We support this effort, or this fishers’ guild, because it’s the same wrong, it’s the same damage that’s harming us,” said Oswaldo Contreras, president of the Río Dulce Tourism Commission. “As the Tourism Commission we support everything that has to do with the issue of conserving our environment. This [mine] has come to threaten our environment too because in El Estor [the mining company] has destroyed the whole mountain.”

The fishers’ pollution and environmental concerns are shared by residents of Río Dulce, but the latter also contend with the near-constant mine and other industrial traffic passing through the center of their town and over the scenic bridge spanning the Dulce River. People have been killed and maimed by heavy trucks passing through the area, residents said. The road damage, the dusty air, and the noisy air brakes trucks use on the bridge are all affecting residents, livelihoods and business, according to community leaders, hotel and restaurant owners, and other locals. They laid out their concerns at a roadside eatery, pausing every now and then as trucks barreled past.

“We’re a tourist town. We’re not an industrial zone,” said Río Dulce community development committee president Emilio Mendizábal. “What these people are doing is impoverishing us,” he said of the mining company.

Heavy traffic carrying ore from the Fenix nickel mine to the port in Puerto Barrios is causing a series of problems for residents of the region, including fatal accidents. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Heavy traffic carrying ore from the Fenix nickel mine to the port in Puerto Barrios is causing a series of problems for residents of the region, including fatal accidents. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Government Responds With Dialogue, Then Repression

While the El Estor fishers’ 12-day protest action was going on, a few meetings were held between representatives of the GPA, municipal, departmental and national authorities, and the local Solway Group subsidiaries. Government and company officials urged the GPA to lift their action, promising to provide access to studies and documentation and address the fishers’ demands in talks.

The GPA leadership did not formally agree to anything at the third meeting on May 13, but suspended the roadside protest the following day in order to give the dialogue process a chance. May 27 was set for the next meeting of the tripartite dialogue. No location was fixed for the meeting, though GPA leaders always maintained it needed to be in El Estor, the site of the conflict and where initial talks were held, and not government officials’ preference of Río Dulce, where the May 13 meeting took place.

Three days later, the mayor and entire municipal council of El Estor filed a formal report with the Office of the Public Prosecutor, accusing seven people of illegal detention, incitement to crime, coercion and threats. The mayor traveled to Guatemala City and made public declarations encouraging security forces to intervene. One of the previous meetings had been held publicly in the municipal hall, and local officials allege they were subsequently chased and threatened. The GPA maintains it had nothing to do with any tumultuous follow-up to the meeting. The formal report, however, was filed against GPA vice president Eduardo Bin, other GPA members and key supporters, as well as a former municipal employee GPA leaders say had nothing to do with anything.

GPA leaders received no news or notification concerning the May 27 roundtable dialogue meeting, and viewed the criminalization attempts of the municipal council as an act of bad faith in the midst of a dialogue process. Regardless, the GPA membership planned to gather that morning in El Estor to await the officials. When they did, they found out that the Izabal department governor had sent a notification informing them that the meeting was at 9am in Río Dulce. The notification, however, was delivered at roughly 9pm to the local parish, not to the GPA.

Government and company officials arrived in Río Dulce and made no attempt to communicate directly with the GPA gathered in El Estor. The fishers waited until noon on May 27, and then picked up the protest action they had suspended for talks, this time with a full blockade of the road. Each side blamed the other for rupturing the dialogue process, but things soon became clear. It wasn’t just the last-minute, indirect notification about the meeting location: the government had also replaced the local police chief the day before, and riot police were already in the area.

Police from the Division of Police Special Forces, usually dubbed riot police due to their deployment for crowd control, were already on scene May 27 in El Estor when local fishers set up a road blockade to protest mining. They fired both tear gas and bullets. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Police from the Division of Police Special Forces, usually dubbed riot police due to their deployment for crowd control, were already on scene May 27 in El Estor when local fishers set up a road blockade to protest mining. They fired both tear gas and bullets. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Following the violent eviction of the fishers’ blockade and the police killing of Carlos Maaz Coc, police quickly withdrew from town. There were no confrontations or weapons in the immediate area where police shot at unarmed protesters and fishing families. However, little groups of people had reportedly popped up elsewhere, and several police officers were injured.

Immediately following the killing of Maaz Coc, the riot police left, but so did every single police officer regularly assigned to El Estor. Municipal authorities were nowhere to be found. The state had completely abandoned the town. That same afternoon, following the killing, the police station was ransacked and set on fire, as was the mayor’s house. A store owned by a member of the municipal council was looted. Shops closed and town traffic had grinded to a halt.

That night, several hundred police officers and special forces from around the country were sent to El Estor and positioned themselves at strategic points around town.

Following the violent eviction, killing and other incidents May 27, hundreds of police arrived in El Estor overnight. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Following the violent eviction, killing and other incidents May 27, hundreds of police arrived in El Estor overnight. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

In a company statement regarding the events of May 27, the Solway Group attributed the violence to armed conflict between protesters and police, and attributed the road blockade first to criminals and then to “respected fishermen led by the group of troublemakers.” The company, Solway Group and subsidiaries CGN and Pronico wrote, “was not part of the armed conflict between the police forces and a group of protestors [sic].”

The company statement also addressed accusations of pollution due to its mining activities. “The Company’s contribution to the water pollution is minimal,” according to the statement, citing government findings. Environmental officials have stated that 90 percent of water pollution Lake Izabal stems from communities along the Polochic River, which flows into the lake.

Communities and the GPA are skeptical of the studies presented by government officials. After all, officials also stated that no one was killed in El Estor on May 27. Police were the only state entity present and no national journalists were on scene during the blockade and killing, but initial government statements and media coverage presented a hodgepodge of conflicting reports, most of them false.

Someone died. Maybe someone died. No one died. All three versions of events were put forward by government officials at different times. The Ministry of the Interior, for example, published a statement on May 27, recognizing that a civilian was dead. In a statement the following day, however, the same ministry stated that, “after security patrols attending to the honourable citizenry, it was determined that no one died yesterday.”

Shot and killed by police on May 27, Carlos Maaz Coc was buried the following day. The day of his burial, the Ministry of the Interior stated that no one had died. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Shot and killed by police on May 27, Carlos Maaz Coc was buried the following day. The day of his burial, the Ministry of the Interior stated that no one had died. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Amid Ongoing Intimidation, Locals Demand Justice

In the wake of May 27, GPA leaders and others who support the guild have been the targets of criminalization and intimidation, according to GPA president Cristóbal Pop. He and GPA vice president Eduardo Bin are regularly followed by police, he said.

“Every time we go out, the police patrol trucks appear. They’re following us… We’re suffering this intimidation. It prohibits us from going out. We don’t even have the freedom to go work. It’s quite worrisome to us,” said Pop. “We can’t just go out and walk freely because, according to our understanding, they want to arrest us as soon as possible, on the part of the [mining] company.”

Pop wasn’t among the seven people accused by the mayor and municipal council in mid-May, but now there are more formal complaints and proceedings, he said. GPA leaders were informed that the mining company filed a report with the Office of the Public Prosecutor against Pop, Bin, and others. They’re concerned GPA leaders could be accused and tried for the arson at the mayor’s house and police station and other incidents that occurred in El Estor following Maaz Coc’s killing.

“They’re accusing us in this way so that we feel threatened. We have nothing to do with that, the guild [had] nothing to do with what happened,” said Pop.

On May 28, El Estor residents woke up to find their town filled with hundreds of police officers and police special forces from around the country. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

On May 28, El Estor residents woke up to find their town filled with hundreds of police officers and police special forces from around the country. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Bin was among the seven accused by the mayor and municipal council and he’s also among those accused in the formal complaint reportedly filed by the mining company. To Bin, the accusations, being followed by police, and other acts of intimidation are part of a scheme, and it’s not the first time nor place it’s played out this way.

“To me, these are the strategies that companies use to delegitimize our resistance, our struggle, but I think they’re not going to be able to intimidate us with this,” he said. “Everything they’re plotting against us is to delegitimize our struggle and our resistance. It’s a scheme that they use to criminalize our compañeros and also us as the guild, and that’s what they always seek.”

Despite the ongoing intimidation, the GPA took to the streets again on July 7, leading a march from one end of El Estor to the other, ending at the site Maaz Coc was killed. The fishers once again raised their concerns about mining and lake pollution, called for government action, and demanded justice for the killing. The march marked 40 days since hundreds of Maya Q’eqchi’ accompanied his burial in the town cemetery following a procession from the home Maaz Coc, 27, shared with his 22-year-old partner Cristina Xol Pop and their 8-year-old son, Abner Estuardo Maaz Xol.

Local Maya Q’eqchi’ continue to demand justice for the May 27 killing of Carlos Maaz Coc. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Local Maya Q’eqchi’ continue to demand justice for the May 27 killing of Carlos Maaz Coc. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Maaz Coc had lunch at home the day he was killed, Xol Pop said in an interview following the burial of her partner. A member of the GPA, the young fisherman spent the morning with the guild, awaiting the arrival of government and company officials. He then went home for lunch before heading out again to the blockade.

“He always goes, but he always comes back, but now that he left he didn’t come back. He came back, but he was already dead,” said Xol Pop, tears streaming down her face.

The family subsisted largely from Maaz Coc’s small-scale fishing activities, and Xol Pop doesn’t know how she’s going to get by and provide for their son, who is currently in the second grade. She holds the government responsible for Maaz Coc’s death and wants the government to provide for their son’s education.

Cristina Xol Pop, 22, doesn’t know how she will provide for her 8-year-old son following the May 27 killing of the child’s father by police. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

Cristina Xol Pop, 22, doesn’t know how she will provide for her 8-year-old son following the May 27 killing of the child’s father by police. (Photo: Sandra Cuffe)

“It was the police,” said Xol Pop. “The police came just to fight. They started firing tear gas, and they started to shoot.”

“I want justice,” she said.

Parts of this story, including photos and interviews, first appeared in a series of articles published in Spanish by Prensa Comunitaria, an online Guatemalan community news site.

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.